“Great movies are the ones that stay great no matter where you watch them.” Seventy three characters never read so compellingly.

“Great movies are the ones that stay great no matter where you watch them.” Seventy three characters never read so compellingly.

This little nugget popped up in my Twitter feed Friday afternoon on October 4th, a direct result of the mid-afternoon jamboree that took place on the opening day for Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity. You may be familiar with this film by now; it’s the one where Sandra Bullock and George Clooney spin aimlessly through space for roughly ninety minutes in the long, unbroken shots that serve as Cuarón’s calling card (and have done since 2001’s Y Tu Mamá También). According to the Internet, you should probably – probably – make a beeline for your nearest multiplex and watch it immediately, and preferably in IMAX.

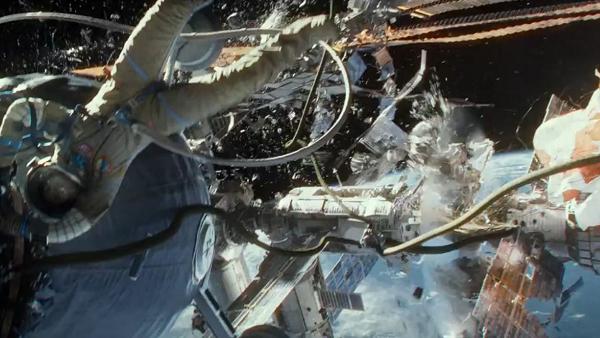

But that’s neither here nor there. Apart from Ms. Bullock, who may make an appearance at this year’s Oscars facing off in a cage match against Cate Blanchett and Kate Winslet for Best Actress, Gravity‘s signature element lies in its effects work; working in tandem, Cuaron, cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, and Visual Effects Supervisor Tim Webber have pulled off the pretty incredible visual feat of converting the space odyssey experience into a screen experience with startling, sometimes outright alarming, verisimilitude (if you’re a pleb, like me, and not a brilliant astrophysicist/party pooper like Neil deGrasse Tyson). In more specific terms, they’ve created a film that encompasses the concept of cinematic immersion more perfectly than any other 3D feature released to date. If you elect to skip Gravity while in theaters, you’re doing yourself something of a disservice.

Nearly every positive reaction to the movie comes buttressed with a claim to that precise effect, which leads us back to the statement prefacing this piece. With Gravity just beginning its theatrical run, there’s no objective way of telling if the film’s artistic achievements will shine quite as brightly in a home theater environment; perhaps, then, starting this conversation now is just jumping the gun. Maybe Gravity can only get better in a more intimate setting. (Most likely not. But I digress.) At the same time, the quoted text offers some not insignificant food for thought, and if we can’t yet adjudge Gravity‘s merits from the comfort of our couches, it’s worth taking a stab at the quoted text and pick our way through its numerous layers of meaning.

At first blush, the idea that great movies should be great regardless of how, when, and where you choose to screen them seems like nothing more than straight-up wisdom. In fact, it should apply to just about any art form or discipline, and not simply cinema; whether you’re reading a beaten up paperback edition Fahrenheit 451 or viewing it on your brand new Kindle Paperwhite, it’s still Fahrenheit 451 and therefore maintains all the excellence of its craftsmanship from one platform to the next. Similarly, the evocative impact of a great painting (Goya’s El Colosso) or a great photograph (Shirin Neshat’s Divine Rebellion) should hold whether they’re observed in person or through a magazine spread. The format is just a delivery system; the art should speak for itself. Or at least that’s the theory.

Truthfully, this line of thinking destabilizes slightly when the subject moves toward visual arts of any kind – for all the awe one may feel looking at a reproduction of El Colosso courtesy of the Internet, trust me when I say it’ll give you severe goosebumps if you ever get the chance to see it up close – but especially when the form in question is film. More so than painting or photography, film has an arena in which it is categorically best received, and that’s, of course, the theater, a house specifically designed to screen movies for audiences when there’s no other way to view them. Even today, films are made not with the home experience in mind but the theater experience; put another way, movies are meant to be seen in a theater first, and on a 60″, high definition, 3D-enabled TV second.

I’ll admit I’m opening myself up for trouble in two different ways here: one, art aficionados may wish to argue (and they’d be correct) that paintings, photographs, and sculptures should be seen in a gallery or a museum designed to showcase them for maximum effect; and two, the advent of the accessible (well, more accessible) home-theater set-up and the availability of on-demand content through services like Netflix Instant, Hulu, and iTunes have put a huge dent in the relevance of the modern cinema. But movies, more than other works of art, are truly meant to be seen in a theater – all but the most high-end (read: absurdly, exorbitantly priced) home theater systems don’t even come close to touching the quality in presentation one enjoys while watching a film in a theater, be it a multiplex like AMC or a local arthouse like the Brattle. Only recently have home theaters increased in potency to the point where they give actual theaters a run for their money; it’s an issue of technology first and aesthetics second, whereas bringing a painting home embodies the reverse dichotomy.

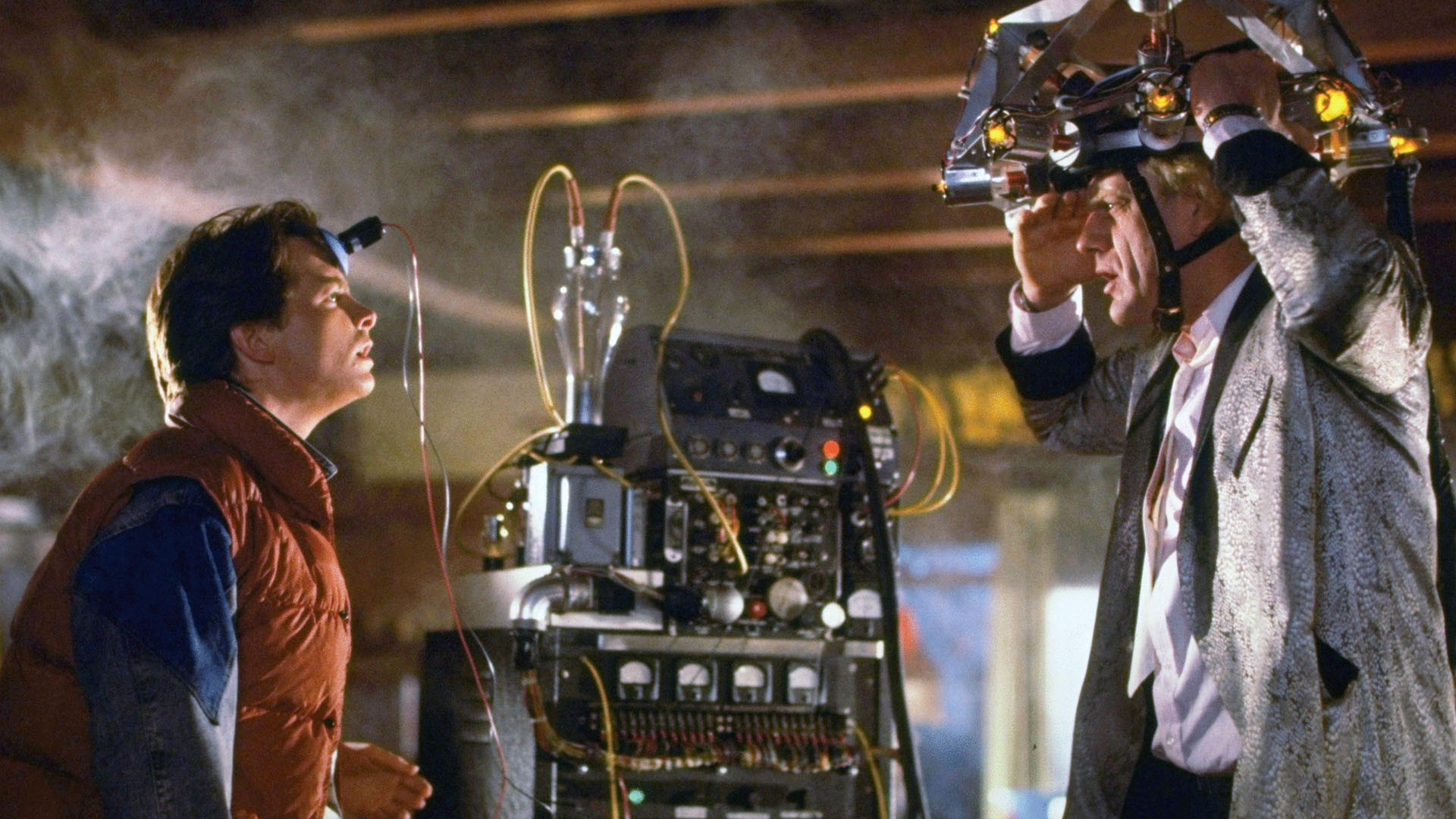

This is all a very roundabout way of saying that film is unique among art forms explicitly due to the nature of how and where they’re intended to be seen, which is itself an unwieldy way of saying that movies should be crafted to maximize the practice of watching them in a theater first and foremost. Therefore, if a great movie works best on a big screen and suffers in the transition to home theaters, that most certainly isn’t strictly a knock against the film itself; pictures like Gravity, or Ang Lee’s The Life of Pi, or Guillermo del Toro’s Pacific Rim, or Peter Jackon’s upcoming The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug can’t be penalized for taking advantage of the medium to its fullest extent, and for relying on the most prominent stage in their field for presentation. (Allow me to acknowledge that a huge number of people didn’t like what Jackson did with 48 FPS for the first Hobbit movie, and probably won’t like it in the next two.) Boiled down to the essentials, they’re artists making art using the tools associated with their chosen trade.

So they should use those tools accordingly, and make art that strikes truest within the confines of the cinema. Shouldn’t they? Every movie looks better in a theater setting, whether it’s a tech-driven piece of spectacle like the films mentioned above or something of a smaller scope, like Short Term 12, Moonrise Kingdom, Beasts of the Southern Wilds, Stoker, or Drinking Buddies. What’s the benefit of thinking small and making a movie to fit within the reductive boundaries of home viewing? Does that progress film as a discipline, or hold it fast in artistic arrested development? Yes, a good movie, like any lasting work of art, will be great no matter where you see it and how; that’s a testament to the power of a narrative that’s made smartly and with care. (Though it’s worth pointing out that nothing looks good on the minuscule sets provided by airlines for our entertainment on long flights.)

But none of this is to say that all movies should be treated as though they aren’t more effective, more evocative, more moving, more inspiring, and more successful as narratives when we see them in a theater. The cinematography of a film like Before Midnight, which can simply be described as “stunning”, leaves even more of an impression when absorbed through the proportional majesty of the theater; so too do Gravity‘s assured, gliding, unbroken tracking shots when seen in IMAX, the sensation of which may indeed be lost in translation when Cuaron’s movie passes on to home media.

But that won’t be a knock against Gravity so much as a knock against the limits of what we can reasonably expect out of home theaters.

2 Comments

Colin Biggs

I was having a conversation with a girlfriend’s uncle and he was telling me that his home theatre was just as good as anything he could see short of IMAX. That’s all good and well, but when a film gets judged negatively for it then I don’t think it’s fair.

Great article.

Andrew Crump

Thanks bud! And I’m totally with you – I don’t see much sense in giving a movie reduced marks for being less flashy in a home theater setting than in a cinema setting. Of COURSE it is. ALL movies are. So judging them as lesser when you switch formats seems fundamentally unfair.