What’s most impressive about Romanian filmmaker Cristian Mungiu’s morally complex drama, Beyond the Hills, may well be his insistence upon remaining firmly in the grey rather than taking sides. Another filmmaker might have examined this tale, based on a real-life exorcism, and turned it into an anti-religious parable in which science- and only science- possesses the sense and rationality necessary to make sense of and survive in the modern world. That’s hardly the point Mungiu’s making, of course, but some might draw that precise conclusion regardless of his efforts to make nearly every character in his film culpable in its central tragedy. Just like in life, though, there are no easy answers to be found in Beyond the Hills, only more questions and an overabundance of sorrow.

The set-up is simple: Alina (Cristina Flutur) has tracked down and reunited with Voichita (Cosmina Stratan), her childhood friend, fellow orphan, and implied ex-lover, who has made a new life and found peace for herself in a monastery nestled atop the hills of the film’s title. Their meeting is initially joyous, but the longer Alina stays with her friend and observes the way monastery life has changed her- Voichita no longer accepts Alina’s advances- the more restless she grows. Her frustration eventually leads to outbursts that on the surface are completely understandable, if ill-advised, but the more she lashes out the more she inadvertently convinces Voichita’s fellow nuns- as well as their priest (Valeriu Andriuta), known simply as Father- that Alina has fallen under a demonic influence.

The set-up is simple: Alina (Cristina Flutur) has tracked down and reunited with Voichita (Cosmina Stratan), her childhood friend, fellow orphan, and implied ex-lover, who has made a new life and found peace for herself in a monastery nestled atop the hills of the film’s title. Their meeting is initially joyous, but the longer Alina stays with her friend and observes the way monastery life has changed her- Voichita no longer accepts Alina’s advances- the more restless she grows. Her frustration eventually leads to outbursts that on the surface are completely understandable, if ill-advised, but the more she lashes out the more she inadvertently convinces Voichita’s fellow nuns- as well as their priest (Valeriu Andriuta), known simply as Father- that Alina has fallen under a demonic influence.

Things escalate from there, albeit slowly. Mungiu isn’t in a hurry to arrive at Beyond the Hills‘ denouement, but there’s no reason for him not to take his time considering the articulateness of his cinematic language. Yes, this is a lengthy film, and one that’s utterly lacking in flashier varieties of showmanship, but Mungiu’s technical chops should provide plenty of artistic dazzle on their own merits. Told in long, uninterrupted takes, Beyond the Hills moves ponderously but with force and impact; many of the scenes feel like micro-narratives of their very own, one-offs that Mungiu stitches together with cohesive precision to tell the whole of his story. At times, the film is about Alina’s and Voichita’s fractured relationship; at others, it’s about the desperation and limitation that defines life for inhabitants of their village; at others still, it is, admittedly, about the struggle between science and religion, but no victor emerges at any point in their ideological back and forth.

Ultimately Mungiu finds a harmony in each of these ideas and presents us with a heartbreaking, complicated portrait of Romanian life- or at least a microcosm of Romanian life. There’s sparse beauty to be found in this realm, courtesy of Mungiu’s aesthetic, but just as much tragedy if not more. Options are few for people like Voichita and Alina; staying in town likely means working at a car wash, like the latter’s brother, Ionut, for the rest of their lives. They’re also free to leave, but Alina’s the only person we meet in the film who chooses to do so, and life eventually pulls her back to her former home despite her best attempts to escape. It’s a point Mungiu articulates quite clearly- how do people survive in a country whose very infrastructure turns everyone away like Mary at the inn?

Even when Beyond the Hills has come to a close and everyone has met their respective fates, it’s easy to see the appeal of monastery life in a region that’s so desolate. In exchange for routine worship, manual labor, and devotion to a simple, chaste existence, Father can put a roof over a person’s head, keep them fed, and lead them to a sense of spiritual serenity. Given the alternatives that are available, the trade-off seems like something of a bargain; at the very least, it works for Voichita, who asserts that she’s found peace in monastery life that she simply couldn’t achieve anywhere else.

And who’s to say she’s wrong? In truth, it’s only when Alina re-enters her world that Voichita’s tranquil veneer begins to splinter. Therein lies the crux of blame in Beyond the Hills; there’s plenty of it to go around. Alina’s stubbornness, the superstitions and beliefs of the church, and the hospital’s lack of hospitality are all factors in the film’s woeful climactic mishap. In the fallout of that event, everyone takes turns pointing fingers at one another- Father and the nuns trade accusations with police officers and physicians alike- but behind his camera, Mungiu remains impassive.

Who does he hold liable here? It’s a question that goes unanswered all the way up to the film’s final shot. Ultimately, the burden of judgment is left to his audience, but it’s incorrect to single out any one group here as being more responsible than the others. Ambiguity marks the most binding element of Beyond the Hills; we’re unsure of who to condemn just as we’re unsure whether Alina’s a victim of dogmatic religious ignorance or of possession. The neo-realist style Mungiu applies to the proceedings suggest the former- there’s no such thing as demons in the real world- but the film’s roots in reality invite us to consider the latter possibility as well, no matter how far outside the realm of verisimilitude it falls.

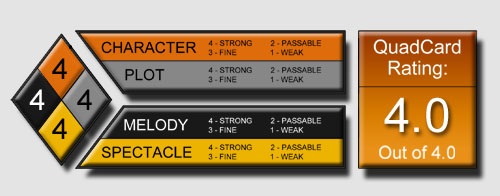

G-S-T Ruling:

The over-arching portrait Mungiu draws here, though, is one of despair. Beyond the Hills looks gorgeous and boasts applause-worthy craftsmanship, but it’s an ugly picture at its core. When any movie ends as this one does, there’s very little use in determining who the guilty parties are, and the fact that the human stupidity and callousness documented in the film goes unpunished within its two and a half hour body makes it a tough- but rewarding- pill to swallow.