Ginger & Rosa, the latest and possibly most accessible picture to come from British filmmaker Sally Potter, represents a coming of age for Elle Fanning as much as it does for the character she plays. Structurally, the film is pretty standard stuff; as the Ginger of the title, Fanning confronts or falls into situations beyond her age bracket and goes through the painful emotional transformation from child to woman in a scant eighty four minutes of narrative. But Potter has never been a standard director, nor should Fanning be seen any longer as a standard actress. Amazingly, Ginger & Rosa proves an astronomical leap forward for the latter and a half-step backward for the former.

Ginger & Rosa, the latest and possibly most accessible picture to come from British filmmaker Sally Potter, represents a coming of age for Elle Fanning as much as it does for the character she plays. Structurally, the film is pretty standard stuff; as the Ginger of the title, Fanning confronts or falls into situations beyond her age bracket and goes through the painful emotional transformation from child to woman in a scant eighty four minutes of narrative. But Potter has never been a standard director, nor should Fanning be seen any longer as a standard actress. Amazingly, Ginger & Rosa proves an astronomical leap forward for the latter and a half-step backward for the former.

Which is not at all to say that the rest of the film is lacking- it’s just oddly normal coming from an auteur who premiered her last picture via cell phone. Ginger & Rosa may fit the bildungsroman bill, but Potter handily demonstrates that these sorts of archetypes are well worth exploring so long as the storyteller has valuable or interesting to say. In this particular case, the big takeaway appears to be that Elle Fanning is destined to be the next great actress of our time; the film may as well have been called simply Ginger, as its completely hers through and through.

Which is not at all to say that the rest of the film is lacking- it’s just oddly normal coming from an auteur who premiered her last picture via cell phone. Ginger & Rosa may fit the bildungsroman bill, but Potter handily demonstrates that these sorts of archetypes are well worth exploring so long as the storyteller has valuable or interesting to say. In this particular case, the big takeaway appears to be that Elle Fanning is destined to be the next great actress of our time; the film may as well have been called simply Ginger, as its completely hers through and through.

There’s no way to say that without doing a disservice to Alice Englert, whose work as Rosa proves that she really is that good and her performance in Beautiful Creatures wasn’t a fluke. But Englert isn’t Potter’s principal focus, and Rosa winds up being less of her own character and more a catalyst for transformation in Ginger. Ginger & Rosa begins as a portrayal of their childhood bond, forged in the atomic ashes of Hiroshima seventeen years prior to the events of the film; when we meet the two teenaged girls, they’re shrinking their blue jeans in the tub, listening to jazz music, snogging boys at concerns, and smoking cigarettes. They’re also nipping at the heels of adulthood in a time of nuclear paranoia, where apocalypse could be lurking just around the corner. Ultimately, it’s that fear of global destruction that shoves a wedge between them, but not for the reasons one might suppose.

By circumstance and by parentage, both of them are forced to grow up fast. We only see Mr. Rosa in the movie’s opening scene, after which he swiftly disappears and Rosa has to help care for her two siblings. Good fortune sees Ginger grow up with a father figure in her life, but for the fact that Roland (Alessandro Nivola) may do more harm by being present than Rosa’s dad does through his absence. He’s an intellectual and an idealist, a pacifist and a conscientious objector who believes in independence and personal autonomy; he instills many wonderful traits in Ginger, teaching her to think for herself, but he’s oblivious to the dangers inherent in conflating his ideologies with parenting techniques.

We bear witness the damage his irresponsibility has wrought in Ginger & Rosa‘s final act, where it becomes clear that Ginger isn’t equipped to live in a world that could end in the blink of an eye. Truthfully, we’ve already seen the effects of his reckless self-obsession in a second-act quarrel between Roland and Nat (Christina Hendricks), Ginger’s mother. Here, the film becomes one about gender inequity; Nat, a former artist, put her paintbrushes away to care for Ginger after her birth while Roland appears to have made no sacrifices himself (though were you to tell him this, he would almost certainly claim that his professorial duties constitute precisely that).

So Ginger & Rosa embraces its period setting, but no matter where Potter takes the film, she keeps Fanning at the center of it all. Normally, Ginger might just be a bystander, the audience surrogate who serves as our eyes and ears in a bygone era; here, she’s as integral to the experience of watching the movie as Potter’s camera. Part of that has to do with Fanning’s absolutely extraordinary performance, but Ginger isn’t just the cipher through which we’re introduced to the world of 1960s post-war Britain. She’s a bona-fide character, well and fully realized and brought to startling, vulnerable life courtesy of Potter’s script and Fanning’s wide-eyed, guileless naturalism.

It’s impossible to over-emphasize the depth of her acting here. In point of fact, Fanning seems like she’s just being rather than acting, so to speak; it’s the sort of performance only a child, unacquainted with managers and diva behavior and not yet jaded by Hollywood culture, could give. She’s so good that in a cast of proven, veteran actors and actresses, Fanning towers above everybody, from Timothy Spall and Annette Bening, playing family friends, to Hendricks, who struggles with her English accent. Fanning’s best moments actually spring from the time she spends on-screen with Englert- they fluctuate between the bliss of friendship and sisterhood and the cruel sting of betrayal with honesty and aplomb.

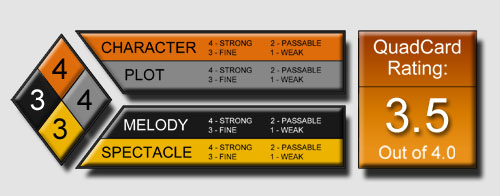

G-S-T Ruling:

From behind the lens, Potter maintains a firm grip on Ginger & Rosa even as she slackens the reigns on Fanning. The tight, exquisite craftsmanship contrasts with Fanning’s unrestrained, wholly real performance, suggesting that Potter funneled her energy into technical areas and felt comfortable just letting her star be. She’s working primarily in confinement, keeping close to her protagonist so as to highlight the confusion and discontent brought on by her many growing pains; that emotional claustrophobia is woven together with open spaces both natural and man-made, but even when Ginger goes sailing or lays down on snow-capped grass she can’t quite find the peace she so desperately wants. In a film this brief, that could well be the point: the answers never come to us easily, and when Ginger begins pouring her heart into a poem just before the credits start rolling, she all but confirms that notion at the tip of her pen.