How does a child endure the trauma of a volatile custody battle? What Maisie Knew, loosely based on Henry James’ 1897 novel of the same name, answers that question by putting central emphasis on the titular character, a precocious young girl caught between her two warring parents in the final days of their poisonous marriage. Sometimes, Maisie (Onata Aprile), is nothing more than a bargaining chip alternately used by her father, art dealer Beale (Steve Coogan, affecting his finely-tuned persona of self-absorption), and her mother, has-been rocker Susanna (Julianne Moore), in their legal and social skirmishes; at others, she’s a silent witness to the selfishness of grown-ups and, to a limited extent, her own caretaker, fishing out pizza money when mom and dad are too busy quarreling to pay the deliveryman.

But at all times Maisie is an object of neglect who craves the attention and love all children are due in their formative stages. Her story comes to us courtesy of filmmaking/screenwriting duo Scott McGehee and David Siegel, whose joint filmography is so bland that seeing them produce something this affecting is nothing short of revelatory; they’ve loosely adapted Henry James’ 1897 novel of the same name, re-purposing it for modern times and setting it in New York. By and large, the story remains the same, following the course of Maisie’s life as her parents fight with vicious, underhanded guerrilla tactics to maintain sole guardianship over their daughter, whose quietude belies her skills as an observer of character.

But at all times Maisie is an object of neglect who craves the attention and love all children are due in their formative stages. Her story comes to us courtesy of filmmaking/screenwriting duo Scott McGehee and David Siegel, whose joint filmography is so bland that seeing them produce something this affecting is nothing short of revelatory; they’ve loosely adapted Henry James’ 1897 novel of the same name, re-purposing it for modern times and setting it in New York. By and large, the story remains the same, following the course of Maisie’s life as her parents fight with vicious, underhanded guerrilla tactics to maintain sole guardianship over their daughter, whose quietude belies her skills as an observer of character.

The differences come down to decisions that McGehee and Siegel make regarding Maisie’s ultimate fate and Mrs. Wix, a supporting player who appears in a single scene before disappearing into the horizon for the rest of the film. For those who haven’t read the book, the significance of these elements will have no real meaning, so their particulars won’t be divulged here. Suffice to say that McGehee’s and Siegel’s choices in transitioning James’ work from page to screen yield a story that manages to be both open-ended and optimistic at the same time. If anyone needs an idea of what smart adaptation looks like, they need only look so far as What Maisie Knew; they effortlessly walk the line between keeping the spirit of the source material intact and putting their own stamp on it.

Through their lens, Maisie’s world feels appropriately large and beyond her scope as a child. Cleverly, the camera is set to match her perspective, cutting out the upper torsos of the adult cast in countless frames and giving us the opportunity to truly watch events unfold from Maisie’s disempowered position. We’re consistently, but not constantly, restricted to this mode of experiencing What Maisie Knew; it’s a technique which the filmmakers employ with a judicious sense of control, wisely using it only when necessary and without neglecting the point of view of their other characters. It’s almost as important for us to get a sense of Maisie through the eyes of her caretakers as the other way around.

In fact, without that relationship between the way these characters see each other, What Maisie Knew would be a much poorer film. For Susanna, Maisie is something to be possessed; she allows no one to get close to her, not even Lincoln (Alexander Skarsgard), the man she marries once she and Beale finalize their split. On the other hand, Beale has no idea what to do with his daughter; he loves her, clearly, but he’s rudderless as he struggles to navigate the choppy waters of parenthood. Through it all, Maisie slowly learns how to suss out the truth of her parents, eventually coming to the unspoken understanding that they’re both irreparably damaged people focused on their own needs ahead of hers.

That’s not to say that McGehee and Siegel think they’re beyond redemption; in the movie’s closing moments, Susanna drives right to the edge of grotesquerie before she reigns herself in and shows off some long-hidden humanity. Beale gets no such moment, and exist stage left rather unceremoniously three quarters of the way through the picture, but he’s not a cruel man despite his dereliction- just a terribly weak one. Ultimately the message here is that no matter how much a child is disregarded by their family, there are people out there capable of loving them; that’s where her nanny and Beale’s second wife, Margot (Joanna Vanderham, exuding subtle and overt vulnerability), and Lincoln both come in, albeit at very different times, to atone for the sins of the film’s adult contingency. Maisie isn’t alone. She just hasn’t found her way into the care of people who really love her yet.

Apart from McGehee’s and Siegel’s shrewd, assured direction, What Maisie Knew‘s other defining component lies in the realm of performance. Ms. Aprile is so remarkably authentic and aware of each action she takes from scene to scene that audiences and critics are going to be naturally drawn to her work here; hers isn’t the sort of ferocious debut Quvenzhane Wallis made in last year’s Beasts of the Southern Wilds, and instead impresses on a far more restrained level. Her elders, meanwhile, each take stellar turns in their respective roles- notably Skarsgard, who sheds his hunky True Blood persona to adopt Lincoln’s gentle, nearly child-like timbre, and Moore, reliably excellent but better and more layered here than she has been in years.

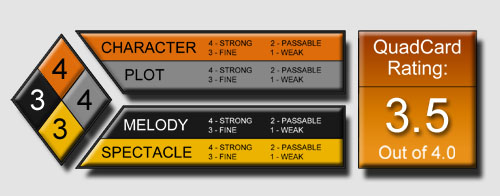

G-S-T Ruling:

She’s key to the film’s capstone moment, where everything comes into a perfect clarity of vision. No screen parents in 2013 are quite so appalling as she and Beale, who together rob Maisie of her innocence without even realizing it. But through her adversity, she develops a hushed yet palpable strength that finally rises to the surface as she confronts her mother for the final time in the picture. What Maisie Knew is peppered with moments of great, nuanced cruelty, but at its heart it’s a children’s film in the purest sense possible- one in which the fledgling protagonist learns who really has her best interests in mind, and gains the strength to survive and thrive in the face of abandonment. In a season filled with the explosive thunder of blockbusting, that message resonates as loudly as any colorful display of computerized spectacle.