Watching Andrew Stanton’s adaptation of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ seminal science fiction pulp novel, A Princess of Mars– here blandly labeled John Carter– is equivalent to a genre-fueled out of body experience. You’ve seen this film before. You’ve seen it in Star Wars (both the original trilogy and the prequel films), you’ve seen it in Avatar, you’ve seen it in Superman. John Carter‘s influences read so blatantly that watching the film feels akin to playing a movie association game in which elements from its plot and narrative are connected to those of other essential sci-fi blockbusters. What we’re really watching, of course, is the big-screen arrival of the story that informed each of those aforementioned properties and more; to label John Carter“derivative” is to reveal a great misunderstanding about the impact it’s had on genre fiction since 1917.

And so it’s sort of a shame that the film works unevenly. More often than not, the fruits of Stanton’s labors are praise-worthy; at its best, John Carter is exciting, energetic, gorgeous to behold, and defined by impressive world-building and FX work. When the film sputters and falters, the effect is somewhat deflating. In fact, the aspects of the film that fail to satisfy do so in such a noticeable fashion that they end up underscoring just how good the film is when it’s at its best– though that does, in fact, functions in reverse as well.

Burroughs’ original novel concerns the exploits and adventures of John Carter, an American Confederate cavalryman who, through circumstance, finds himself transported to the surface of Mars– called Barsoom by its inhabitants, and which looks an awful lot like the American frontier. Before long Carter finds himself deeply entrenched in the political strife brewing between Helium and Zodanga, two enemy cities that for ages have been vying for dominance of the planet’s surface, as well as the tribal ways of the Tharks, tall, green-skinned, four-limbed humanoids who largely view compassion as weakness and are prone to settle disputes with steel. With minor exceptions, John Carter follows that raw outline fairly closely even if the details differ. Stanton raises an entire world from the ground up, introduces us to a variety of alien races, and impresses the mores of several different cultures upon us, and he does each with equal efficacy. When the film gets rolling, you won’t be lost amid the innumerable crises, characters, and conflicts at its center.

You may, however, find yourself more puzzled by character motivations and framing devices. Strictly speaking, the presence of the Machiavellian Matai Shang (Mark Strong), makes sense; Stanton clearly means to peg Shang and his race as the antagonists in future installments of the John Carter franchise. And yet the logic behind Shang’s involvement here is murky at best. Maybe it’s the racial proclivity of his people to manufacture the downfall of planets, but smarmy, arbitrary super-aliens aren’t especially compelling villains. Most baffling, though, is that John Carter already has a solid villain in Dominic West’s power-hungry warlord, Sab Than, Prince of Zodanga. Sab Than makes for a fine standalone bad guy in the novel; Shang’s addition to the proceedings, then, feels like nothing more than an over-complication and a contrivance meant to set him up as the heavy in the next film.

And then there are the scenes which bookend the story we’re there to watch unfold. Suggesting that Burroughs got the concept for A Princess of Mars by reading his uncle’s diaries is a cute idea– and one that, in fairness, does come up in the novel– but by treatingJohn Carter as nothing more than the sum of the pages in the titular character’s pages reduces the film’s epic stature. Maybe John Carter doesn’t need to be epic, but it wants to be, and actually inserting Burroughs as our audience identification character discovering his uncle’s exploits fights against that big, bold sensibility. And– like Strong’s presence– it’s not necessary. Nothing is achieved with the Burroughs character that couldn’t have been without him.

Part of what makes John Carter frustrating comes from being able to envision, with clarity, just how good the film would be had those two characters and conceits been excised from the script. As a genre epic, John Carter should have scope; the Burroughs character and the Threns stretch that scope out too far for no tangible gain. There’s never a moment where they feel essential. Yet they never incite narrative collapse, either, which speaks highly to the strength ofJohn Carter‘s numerous better merits. Stanton has transitioned to live action with little trouble, though the sensibilities of his work with Pixar crop up here nevertheless. John’s Martian dog sidekick, Woola, for example, feels deeply rooted in Pixar sensibilities– he’s sweet, loyal, lovable, incredibly alive, and handy in a fight– while the film boasts a sense of humor that’s used to great effect in softening the blow of expository dialogue while also attenuating the more grave characteristics of its plot.

And when the time for action comes, John Carter soars. Carter’s battle against a legion of enraged Thark warriors should stick in the cinematic collective unconscious immediately and remain for a very, very long time; it’s one of the best sequences in the film, and years from now should rank among Stanton’s best work. The fact that he gets it right in just about every other action set piece in the film is almost gravy– that’s how good the Thark fight is. Stanton’s approach to filmmaking isn’t fancy, but it is effective. There are no fast, hectic cuts here, just careful, planned shots that cut when they need to and linger when they don’t. Maybe it helps that the effects here are pretty marvelous, but nothing beats measured, precise, and intentional filmmaking, which Stanton uses to John Carter‘s frequent benefit.

As strong as the film is technically, nothing here trumps the performance of Lynn Collins. Collins plays Dejah Thoris, a Princess of Helium and an archetype-shattering female character. Dejah’s royal standing might leave some to assume she’s nothing more than a damsel in distress; like the Princess Leias and the Ripleys of cinema, though, she can more than take care of herself. Not just in combat– though Dejah can fight, and fight very well as John learns to his embarrassment when they first meet– but in the realm of politics as well. Dejah’s powerful, authoritative, and deductive and brilliant; Collins, clearly, gets that, and plays her just big enough without tripping over the line of camp. In the end, Collins’ portrayal of Dejah outshines the rest of the cast– including Taylor Kitsch, her leading man, who’s solid when physicality calls and stumbles the rest of the time– which is no small feat considering the raw talent of the supporting cast. Willem DaFoe, James Purefoy, West, and Ciaran Hinds all turn out good work, but with the exception of Dafoe they’re used too little and never attain the same presence as Collins.

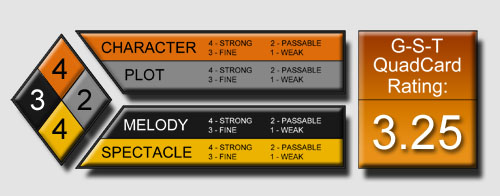

G-S-T RULING:

The problems that stymie John Carter aren’t insurmountable. Nor should they be forgiven, either; they keep the film from being as good as it could be. On that same token they don’t render the picture bad or even mediocre. As to be expected this Old Hollywood style epic is chock full of grandeur and it looks beyond stunning on Blu-Ray; no surprise there. But new to the John Carter experience is an “alternate opening” included in the deleted scenes. In a narrative sense it probably would have served the story better had they used it. Never hurts to give a little history lesson/scientific exposition to get people acclimated to such a foreign world, does it?. Yet for all of the polish the script lacks, there’s vision and ambition here, and for the most part, those two elements carry through with great success. Indeed, it’d be nothing short of a crime if the efforts of Stanton, his cast, and his crew were to be overlooked and ultimately forgotten.