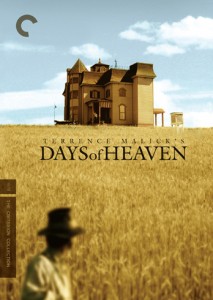

Days of Heaven:

Directed by: Terrence Malick

Written by: Terrence Malick

Starring: Richard Gere, Abby Brooks, Sam Shepard, Linda Manz

Cinematography by: Néstor Almendros, Haskell Wexler

Music by: Ennio Morricone

Released: September 13, 1973

Among the minute number of films Terrence Malick has directed over the course of his decade-spanning career, 1978’s Days of Heaven stands out as his most significant. Maybe it isn’t difficult to rise to the top of a five picture filmography (Malick’s sixth feature length release, To the Wonder, is allegedly due out later this year, and he has two more features tentatively planned to be shot back-to-back soon after), but the purpose of this exercise isn’t about competition; it’s about posterity and influence. Malick may have received more initial acclaim five years prior with the release of Badlands, but Days of Heaven— met with mixed fanfare before being evaluated by critics years later– serves as the better blueprint for what has come to define his aesthetic as a filmmaker.

Among the minute number of films Terrence Malick has directed over the course of his decade-spanning career, 1978’s Days of Heaven stands out as his most significant. Maybe it isn’t difficult to rise to the top of a five picture filmography (Malick’s sixth feature length release, To the Wonder, is allegedly due out later this year, and he has two more features tentatively planned to be shot back-to-back soon after), but the purpose of this exercise isn’t about competition; it’s about posterity and influence. Malick may have received more initial acclaim five years prior with the release of Badlands, but Days of Heaven— met with mixed fanfare before being evaluated by critics years later– serves as the better blueprint for what has come to define his aesthetic as a filmmaker.

The effect of watching Malick’s contemporary work against his fledgling efforts is eye-opening. For best comparison– arguably, at least– watch last year’s The Tree of Life in conjunction with Days of Heaven and observe just how deeply the latter film informs the visual grammar and the style of the dialogue of the former. When we think of Malick, we think of an abundance of striking, beautiful, fluid cinematography and a recurring disregard for spatial continuity; we think of narrative art that flirts with the concepts touted by pure cinema (though it most certainly is not pure cinema itself). In Malick’s cinema, images stand out as their own separate and distinct worlds within each movie instead of providing audiences with data that informs the progression of plot, rapidly flowing from one to the next.

That mercurial quality represents a break from traditional storytelling conventions, and Days of Heaven remains the best example from Malick’s body of work of that schism in action. Like Tree of Life, Days of Heaven rarely takes the time to hold still, airily hopping from one frame to the next like a cinematic stream of consciousness; as the film cuts across the daily operations of Sam Shepard’s farm and depicts the passing of the seasons, we get the strong sense that we’re only seeing partial scenes rather than complete sequences. All the while, the voice of Linda (Linda Manz) drawls over the scenery, offering the musings and insights of a child as she describes the events that occur within the film’s hour and a half running time. Like the wheat fields rustling in the wind, Days of Heaven reads as a breezy affair but for its contrarily morbid, apocalyptic characteristics.

Malick’s story begins in a Chicago steel mill, where we meet Bill (Richard Gere), a laborer who kills his boss in a dispute that’s vaguely defined. Seeking to evade justice, Bill hops on a train immediately following his crime, bringing along with him his girlfriend Abby (Brooke Adams) and his little sister (Manz). After a journey from Illinois to the Texas panhandle, the trio take on work as hired seasonal help on a farm run by a shy, quiet man (Sam Shepard), who takes a liking to Abby under the belief that she is also Bill’s sister (a trick straight out of Abraham and Sarah’s playbook). It spirals from there; the narrative that unfolds as the film arrives in Texas is one founded on dishonesty, and the romantic conflict Bill and the farmer eventually engage in burgeons out of their control. Despite the film’s title and many moments of idyll, Days of Heaven‘s climax much more closely resembles hell on earth.

As locusts swarm and an inferno rages across the farmer’s field of crops, Malick’s picture takes on a decidedly Biblical bent. Bill has spent the entire film outrunning his initial sin, but he never tries to atone for it; instead, he focuses his energy on transgressing further, spreading falsehoods (and convincing Abby and Linda to do the same) before attempting to execute an even greater con. The farmer, we learn, is dying, and Bill encourages Abby to marry him so as to inherit the wealthy agriculturalist’s money once he passes. By the time both men confront one another in the wake of the apocalyptic fire that consumes everything in its path (which Linda unwittingly predicts in an early narration), Bill has layered deceit upon deceit and stands exposed before the farmer’s wroth.

This is where Days of Heaven comes full circle. Pressed into a corner and with nowhere to run or hide from his adversary and from his guilt, Bill repeats history and kills the farmer. It’s a visceral, shocking moment, one that recalls the first scene of the film and invites us to reconsider the events Malick depicts in that brief opening sequence. We know very little about the steel mill foreman or the relationship that he and Bill have with one another, but maybe we can make inferences based on what unfolds between Bill and the farmer. Did Bill scheme against the mill boss? While it’s doubtful that Abby had even cursory involvement in Bill’s kerfuffle with the foreman , it’s certainly possible– maybe even probable– that Bill attempted to sucker him with a different ploy. Given that both Malick and Gere portray Bill as a man who creates his own circumstances, for better or worse, it seems likely that Bill’s own conduct incurred the ire of the foreman and that their scuffle isn’t as random as it appears at a glance.

Yet Bill’s superiors aren’t the only victims of his actions. As the seasons change and the long con Bill impels Abby to undertake against the farmer burgeons beyond their joint control, Days of Heaven quietly reveals itself as a narrative about how one person’s misdeeds can affect the lives of the people around him. Every movement Abby and Linda take is informed by Bill’s decisions and behavior; if not for him they might have remained living peacefully in Chicago. Of course, that takes some credit away from Bill, who at least tries to do right by his family even if his better intentions become tainted with avarice and he leads Linda and Abby down a path of fragmentation and destruction.

It’s appropriate that Bill’s sins should so significantly inform Days of Heaven‘s plot. The title, of course, refers to the time Abby, Linda, and Bill spend together on the farm, the serene and perfect times where their ills temporarily fade away. But Bill never repents for his initial sin, and willfully perpetuates additional transgressions against the farmer using Abby as his accomplice. If there is no sin in heaven, Bill’s very presence on the farm is something of an affront to celestial order, and so the picture climaxes with him being cast out of “heaven”– along with Linda and Abby– before being punished for his crimes by the farmer’s right hand man and a contingent of policemen. Abby and Linda endure; even they separate at the end, though, with Abby heading off on her own and Linda absconding from the boarding school where Abby deposits her. The parting of the ways between these two represents the final fracturing of the family unit as the two women strive to make new lives on earth after their fall.

Malick captures every moment of their journey in what has become his trademark style of filmmaking. Calling upon the expertise of Haskell Wexler and Néstor Almendros to capture the Alberta countryside (though the film is set in Texas, the exteriors were shot in Canada), Malick directs the camera’s gaze to lilting, unanchored effect. In maybe the truest way possible, Malick uses the tool of his trade to observe; the camera fairly floats through the proceedings, unbound by tethers of any sort. There’s something wonderfully appropriate about that now-trademarked approach Malick takes, something almost seraphic, as though we’re watching the film through the eyes of heaven’s custodians rather than its inhabitants. But that’s exactly what qualifies Malick as one of America’s great directors, and what qualifies Days of Heaven as one of his most accomplished works: the film maintains perfect equilibrium in its artistic pursuits and its craftsmanship, yielding a self-contained, fully connected work of harmonic grace.

4 Comments

Paul

I’m sorry but the only film of Malick’s that I might have enjoyed is Badlands. Sitting through Days of Heaven or Tree of Life is akin to having a root canal without anesthetic (that’s the only metaphor I could come up with at the moment). Painful and never ending. If I want to look at beautiful images (and his films do offer some beautiful images- can anyone spell Haskell Wexler?) I can go to a museum.

Andrew Crump

And not watch the work of a ton of great filmmakers who place an emphasis on imagery in their storytelling. Don’t get me wrong, I think Malick is an acquired taste myself, but I think writing him off on that criteria doesn’t do a disservice to him so much as it does the medium; beautiful images backed by substance drive great cinema. I think the problem a lot of people have with his work (and I base this statement on my own personal feelings toward the man before I turned around on him) is that it’s very, very non-traditional and difficult to get into. It’s what makes something like Tree of Life a tough pill to swallow for me.

Sam Fragoso

I’m looking forward to seeing “To the Wonder”. Your opening paragraph makes me think that I need to see “Badlands” before going into any other Malick films. Need to understand his aesthetic.

Glad this series has been renewed.

Andrew Crump

Honestly, I think Days of Heaven is the better starting point but people should see Badlands too, if only because it’s an excellent film.

I’m going to really try to keep this going on a more regular basis. I let it get too far away from me before; I think the new format ought to help me keep up with outputting these consistently.