If seeing history filtered through a melodramatic lens of dishonesty is your idea of a good time, then you may want to consider buying a ticket to The Attorney; you won’t learn very much about the events it depicts, but at least you’ll be entertained by the film’s almost completely decontextualized content. Or maybe you won’t. Anybody who has a weakness for moral courtroom dramas should find themselves thoroughly engaged by first-time South Korean director Yang Woo-seok, who appears to be merrily cherry picking his way toward crafting a thesis on the abuses of government corruption and the moral imperative of lawyers in a society tainted by it.

If seeing history filtered through a melodramatic lens of dishonesty is your idea of a good time, then you may want to consider buying a ticket to The Attorney; you won’t learn very much about the events it depicts, but at least you’ll be entertained by the film’s almost completely decontextualized content. Or maybe you won’t. Anybody who has a weakness for moral courtroom dramas should find themselves thoroughly engaged by first-time South Korean director Yang Woo-seok, who appears to be merrily cherry picking his way toward crafting a thesis on the abuses of government corruption and the moral imperative of lawyers in a society tainted by it.

Everyone else, on the other hand, might be slightly less taken by Yang’s work, which trades on nuance and realism for broad caricature in tandem with soaring theatrics. It’s hard to hold some of these tendencies against The Attorney; secret police who willfully torture innocent college students into false confessions of communism and treason are pretty damn evil, so much so that an alternate, even-handed rendition of this film would probably reach the exact same conclusion. But it would do so, perhaps, with a prodigious reduction in bluster and self-satisfied, one-sided political theater and by rejecting the more overwrought details that define Yang’s production.

Everyone else, on the other hand, might be slightly less taken by Yang’s work, which trades on nuance and realism for broad caricature in tandem with soaring theatrics. It’s hard to hold some of these tendencies against The Attorney; secret police who willfully torture innocent college students into false confessions of communism and treason are pretty damn evil, so much so that an alternate, even-handed rendition of this film would probably reach the exact same conclusion. But it would do so, perhaps, with a prodigious reduction in bluster and self-satisfied, one-sided political theater and by rejecting the more overwrought details that define Yang’s production.

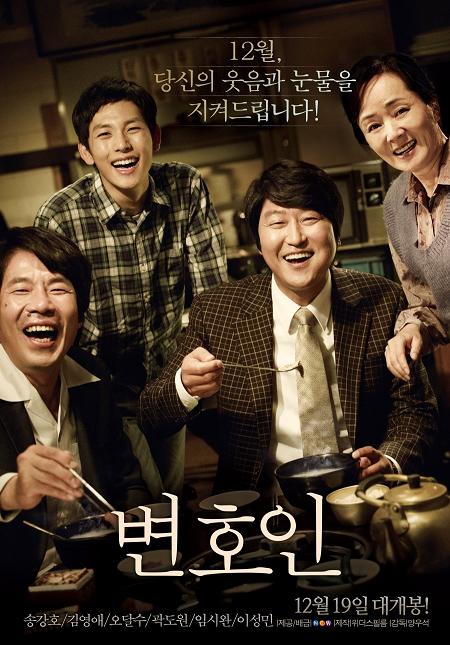

Maybe someday, we’ll get to see that film come to fruition. For now, we can only accept Yang’s version of The Attorney for what it is: a character piece cum love note to the late Roh Moo-hyun, South Korea’s ninth president. The film finds its basis in the early years of Roh’s life before he involved himself in political activism, though his name is never invoked. He’s represented instead by a surrogate screen figure, Song Woo-seok (the great Song Kang-ho), a gregarious sort of scoundrel who’s only in the law game for the money; he leaps from one specialization to another as trends dictate, starting with real estate and continuing with taxes, before ultimately ending up as a defender of the people and champion of democracy.

Woo-seok hustles, but he’s not a totally unscrupulous fellow; he just wants to make bank so he can provide for his family and feast to his heart’s delight on endless bowls of pork stew. (The man eats almost as much as he litigates here. It’s kind of awe-inspiring.) He’s happy to let life’s passing parade trundle onward without giving it so much as a glance. But then Jin-woo (South Korean pop star Im Siwan), student activist and son of Woo-seok’s favorite restauranteur, gets in deep with South Korea’s brutal political police, embodied by merciless jingoist Cha Dong-young (Kwak Do-won), and Woo-seok finds himself moved to take up arms against the regime of then-president Chun Doo-hwan.

Legal arms, that is. The Attorney goes through a rapid change of heart once Jin-woo (along with twenty one other students) gets nicked, whisked away to a makeshift prison, and horribly tortured over a period of months; the film goes from being an upbeat underdog story about Woo-seok hawking his lawyerly talents to whomever he can, to a relatively po-faced courtroom pageant that’s actually about bourgeois gasconade rather than the real circumstances it’s meant to portray. In synthesizing one endeavor with the other, Yang has come up with something that feels almost like propaganda rather than a genuine, insightful account into the moment in time he’s sought to capture.

On some level, that might even be okay; art doesn’t always have to be fair and balanced, after all, and it’s really clear where Yang has laid down his ideological roots. But the tenor of The Attorney suggests that he’s not truly all that interested in exploring the central issue of his narrative. At two hours in length, there’s almost not enough respect paid to the student protests that define the era the film is set in. We see them on TV, Woo-seok and a friend argue over their necessity, but there’s very little sense given of South Korea’s cultural and political climate at the time. The film glosses over the truth, excising the grimmer qualities of the incident; Yang’s preaching to the choir, and all of that sanctimony makes a poor replacement for reality.

Thank goodness, then, for Song Kang-ho. Anyone with even a passing interest in Korean cinema has likely made the acquaintance of Mr. Song through movies like Sympathy For Mr. Vengeance, The Quiet Family, and The Host; across his body of work, he tends to alternate between playing dopey, well-meaning types and serious men of means. He gets to play to both sides here, portraying Woo-seok as affable by nature but fiery in his temperament when the spirit moves him. He’s a sight to behold in either mode, even if he does seem slightly more comfortable when the former part; his versatility is a boon to the film, giving each scene something worth watching at almost every point of its running time. If Woo-seok’s arc is a bit cliched, Song certainly knows how to work its angles.

G-S-T Ruling:

That’s much more than can be said for Yang, who’s determined to work only one throughout the film. His passion for social justice and his outrage toward the atrocities that serve to drive his movie’s plot are both admirable; no one can really fault the guy for making a pissed-off work of art about fighting against blatant governmental injustices. But he’s so caught up in his passionate, righteous indignation that he forgets to tell a cohesive story. The Attorney could have been the vocal piece of protest art Yang wanted it to be and still been executed thoughtfully and with a sense of craft. It’s a shame that we’ve wound up with a film that in the end is just shouting for the sake of hearing its own voice.