Contrary to what the title might suggest, Tim’s Vermeer, is not an art documentary, at least not in the traditional sense. Instead, it plays out like an epic tale of one man’s unusual and fascinating obsession, the promise of discovery it holds, and where this leads both him and the audience as they follow alongside him on this journey. It helps that the film’s subject is an enchanting, not to mention genius, character himself – a requisite for any good story – and it is Jenison’s passion and adamant enthusiasm that propels the film forward and with it, the audience.

Contrary to what the title might suggest, Tim’s Vermeer, is not an art documentary, at least not in the traditional sense. Instead, it plays out like an epic tale of one man’s unusual and fascinating obsession, the promise of discovery it holds, and where this leads both him and the audience as they follow alongside him on this journey. It helps that the film’s subject is an enchanting, not to mention genius, character himself – a requisite for any good story – and it is Jenison’s passion and adamant enthusiasm that propels the film forward and with it, the audience.

In desperate need of stimulating conversation and a break from the day-to-day Penn Jillette, of the illusionist duo Penn & Teller, asked his good friend Tim Jenison to lunch. When Penn leaves the conversation topic up to Jenison, he picks Johannes Vermeer, the 17th century Dutch painter revered for the photorealistic quality of his work. This conversation was the beginning of what would become the documentary, Tim’s Vermeer. With Teller as director and Penn producing, the three men set out to solve a fascinating mystery.

Curious about how Vermeer was able to accomplish such life-like depictions before the invention of photography Jenison developed a theory involving mirrors, lenses and optics tricks. While he’s not the first person to raise questions about Vermeer’s possible use of camera obscura techniques – a number of artists and art historians have theorized on the idea over the years, including “Secret Knowledge” artist David Hockney who Jenison enlists in the film to help test his theory– Jenison takes his methods of experimentation in proving his theory further than any of the previous skeptics.

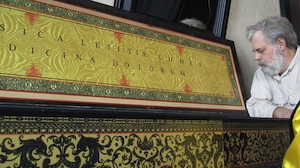

These experiments that result in a decade-long journey and incorporate techniques that include spending over two hundred days creating an exact replica of Vermeer’s studio portrayed in the artist’s painting, “The Music Lesson” – down to ever last detail including the elaborate designs of an ornate table clothe – and then attempting to reproduce the painting in its entirety through the use of a small mirror and a sort of paint-by-numbers method that allows him to copy the reflection of the scene onto the canvas in order to assimilate the painting process he believes Vermeer might have used.

An underlying theme that exists in the film – perhaps by accident – is one of middle aged boredom that borderlines on midlife crisis for both Penn, whose own boredom causes him to invest time and money into the project in the first place, and more obviously Tim, who is a Texas based inventor, technologist and founder of NewTek – a company that revolutionized the digital video and graphics – which affords him the luxury of indulging crazy theories like this one.

The filmmakers were left with around 2400 hours of footage, so one can only imagine the grueling editing process that took place to assemble these pieces together in order to turn it into a compelling story, and this is where the brilliance of the film comes into play. The questions Jenison’s findings raise about the nature of both artistry and storytelling, and the parallels between art and magic it alludes to with the use of mirrors, as a means of creating grand illusions of craft and trickery respectively, are just some of the complex ideas that work to capture the audiences attention. That being said, Penn and Teller’s fun filmmaking style promises a good time even on the most surface level.

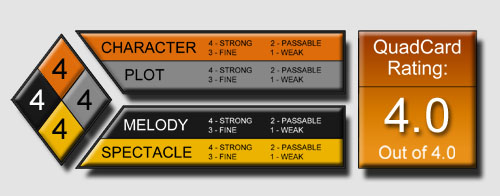

G-S-T Ruling:

With Tim’s Vermeer, Penn and Teller manage to perform one of their greatest tricks of all by teaching the audience about art, cinematic technology, mathematics and magic, all the while making it such a fun ride the viewer hardly realizes they’re learning along the way.