How can anyone review, much less watch, Fruitvale Station without bringing up the 18th Florida circuit court’s verdict in the George Zimmerman trial? The film, which comes courtesy of newcomer Ryan Coogler and marks one of 2013’s most noteworthy debuts, doesn’t reignite national discourse on social justice, race, and the second amendment in the US so much as it reinforces it; to call Fruitvale Station “timely” would be an understatement, though that’s not at all to imply shrewd, heartless planning on Coogler’s or the studio’s behalf. Chalk the picture’s release up to a happy (or unhappy, depending on how you look at it) coincidence, and then gird yourself for a thorough and complex harrowing.

How can anyone review, much less watch, Fruitvale Station without bringing up the 18th Florida circuit court’s verdict in the George Zimmerman trial? The film, which comes courtesy of newcomer Ryan Coogler and marks one of 2013’s most noteworthy debuts, doesn’t reignite national discourse on social justice, race, and the second amendment in the US so much as it reinforces it; to call Fruitvale Station “timely” would be an understatement, though that’s not at all to imply shrewd, heartless planning on Coogler’s or the studio’s behalf. Chalk the picture’s release up to a happy (or unhappy, depending on how you look at it) coincidence, and then gird yourself for a thorough and complex harrowing.

Admittedly, describing Fruitvale Station in terms of its capacity to rile and distress us does something of a disservice to the range of emotions Coogler hits in the film’s brief running time. At times, the story of Oscar Grant ascends peaks of inexpressible joy; at others, quite obviously, it plumbs the depths of human callousness and cruelty, painting a portrait of a cold world in which the threat of violent death is an everyday part of living. But Fruitvale Station makes no attempts to falsely uplift us as it arrives at its inevitable conclusion, ending on a series of somber notes before mercifully fading to black. Whatever else Coogler’s work conveys apart from sorrow and outrage, it’s the sorrow and outrage that remains with us once it’s over.

Admittedly, describing Fruitvale Station in terms of its capacity to rile and distress us does something of a disservice to the range of emotions Coogler hits in the film’s brief running time. At times, the story of Oscar Grant ascends peaks of inexpressible joy; at others, quite obviously, it plumbs the depths of human callousness and cruelty, painting a portrait of a cold world in which the threat of violent death is an everyday part of living. But Fruitvale Station makes no attempts to falsely uplift us as it arrives at its inevitable conclusion, ending on a series of somber notes before mercifully fading to black. Whatever else Coogler’s work conveys apart from sorrow and outrage, it’s the sorrow and outrage that remains with us once it’s over.

And that’s why many, many people will discuss the film in conjunction with Zimmerman’s acquittal for the killing of Trayvon Martin: much like Oscar’s death at the hands of overzealous Bay Area Rapid Transit officer Johannes Mehserle, the event represents a backward step in racial politics in our country and a fresh wound on our collective conscience. But contextualizing Fruitvale Station with the Martin case both dissolves the particulars of Trayvon’s and Oscar’s respective, equally appalling murders, and also overrides Coogler’s efforts to capture a moment in time and tell the latter young man’s story to an audience who may not even know his name. We all bring baggage to the films we watch, but before Fruitvale Station can be analyzed in overarching dialogues about race, it deserves to be processed on its own plentiful merits first.

For those unfamiliar with the tale of Oscar Grant, Fruitvale Station acts as an artful, stylized, and yet wholly down to Earth document of how he chose to spend the final twenty four hours of his life before being murdered at the eponymous Oakland train stop in the early morning of New Year’s Day, 2009. In fact, boiled away of its particulars, Fruitvale Station is just a story about a man trying to turn his life around before dinner, a redemption yarn whose hero determines to become the best father to his daughter, the best boyfriend to his girlfriend, Sophina (Melonie Diaz, no-nonsense but tender and vulnerable), and the best son to his mother, Wanda (Octavia Spencer, reminding us why she has an Oscar), that he can be.

Invariably, that’s going to be a problem for some people, who may see a number of Fruitvale Station‘s plot beats as contrivances and conveniences and subsequently accuse Coogler of falsifying the truth. Happily, those people are incredibly wrong; Coogler does take some dramatic license here and there, cherry-picking incidents that occurred prior to Oscar’s last day on Earth and using them as threads in his personal narrative, but he otherwise sticks to the truth – at least, the truth as it stands in public record as well as first and second hand accounts of the film’s events and Oscar’s character.

There’s no other truth for Coogler to build from, of course, so he’s entirely within his rights to fudge reality where he needs to. But Fruitvale Station draws so much from reality that he overwhelmingly succeeds at approximating it. Unlike the conversations sparked in the wake of Oscar’s death, which alternated between canonizing him and desecrating his character, the film takes aim at his innate humanity and captures a very real snapshot of a flawed person trying to overcome his own demons. Oscar isn’t perfect; he’s hotheaded, he’s unfaithful, and we see him in jail in a flashback sequence, presumably for selling the drugs he later dumps into the ocean in the film’s present tense. Yet he has the desire to change all of that, and if society exists to do anything, it’s to permit people the opportunity to better themselves.

And therein lies Oscar’s journey, one cut short by racially-fueled gun violence. Coogler anchors that quest in the frame of one Michael B. Jordan, who you may recognize as The Wire‘s Wallace all grown up. (He’s in Friday Night Lights and last year’s excellent Chronicle as well, but guess which of these three properties feels the most appropriate as a piece of connective tissue.) It’s a lot of hubris and pressure to describe Jordan’s work here as career-defining – and a bit reductive – but there’s no better way to illustrate the earnest and exceptional qualities of verisimilitude in his work here. I hope that someday, I can look back over Jordan’s body of work and point to Fruitvale Station as the moment where he became a big, huge star; if not, then the guy can claim a truly stellar performance to his credit, which is probably reward enough.

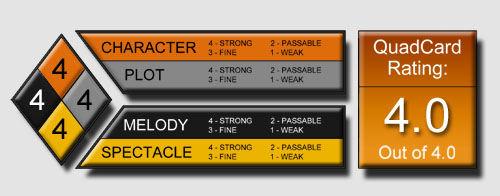

G-S-T Ruling:

For as loudly as Fruitvale Station proclaims Jordan’s talent, it announces Coogler as an emerging filmmaker to watch even more so. This is an assured picture, in part due to the amount of homework Coogler – himself an Oakland native – did in preparation for filming, and in part due to his deep-rooted interest in both the subject and the subtext. Filmed with a poetic yet lilting crispness, his vision of Oscar Grant’s tragedy – and of a world in which such a tragedy can happen – reveal a passionate and topical artist who cares immensely about the social transgressions that shape and define American culture, for better or for worse. Put another way, he has made a film that speaks not simply to a specific event but to contemporary, ongoing travesties, and which demands your attention as well as your patronage.

3 Comments

Squasher88

Great review.

Andrew Crump

Thank you kindly! Glad you enjoyed it. Hope you like the film as much, too!

Squasher88

Yep, I was a fan. http://filmactually.blogspot.com/2013/07/oscar-watch-fruitvale-station.html