The glamour and excitement of Tinseltown come alive when the DSO presents famous movie soundtracks from films like Star Wars, Jaws, Goldfinger, Silverado, Pirates of the Caribbean and more. Take your seat for the best in entertainment with music that ignites the senses in sonic splendor only heard at the Meyerson Symphony Center. But before the lights go down on the evenings of June 6-8, here’s a little glimpse of what to expect from the world-renowned Dallas Symphony Orchestra.

The glamour and excitement of Tinseltown come alive when the DSO presents famous movie soundtracks from films like Star Wars, Jaws, Goldfinger, Silverado, Pirates of the Caribbean and more. Take your seat for the best in entertainment with music that ignites the senses in sonic splendor only heard at the Meyerson Symphony Center. But before the lights go down on the evenings of June 6-8, here’s a little glimpse of what to expect from the world-renowned Dallas Symphony Orchestra.

The following text is from the essay we contributed to the playbill for this Pops concert.

The Hollywood Golden era was a wondrous time in cinema history. The period between the 1930s and the 1950s is fondly remembered for great films, classic scenes, iconic characters and star-making performances. It is similarly held in high regard for the endearing and lavish music composed by great titans of the industry, masters such as Max Steiner, Bernard Hermann, Erich Korngold, Alfred Newman, Dmitri Tiomkin, Miklós Rózsa, Maurice Jarre and others. They were music making machines, sometimes composing close to a dozen film scores a year.

As with anything, though, cinematic tastes changed and the studio system evolved. But as the Golden Age faded into memory, music remained a bedrock of Hollywood myth-making. Tastes change, technology advances, new stars are born – and movie music remains, thrilling us and haunting us, helping directors create new iconic characters and classic scenes.

There’s an idea that the best music is the kind that achieves the desired emotional effect – happiness, sadness, excitement, terror, etc. You feel it but don’t necessarily hear it. Although a score has also done its job if you find yourself humming a few bars afterwards.

John Williams, John Barry and, recently, Klaus Badelt have become synonymous with today’s big Hollywood sound. They are successful Hollywood composers because their music helps audiences get to the core of the film. Their scores become one with the action and are so tailored to character, tone and plot that their music complements the picture in every single frame. They are grafted to the DNA of the story and whether the silver screen glows with tales of gruff archaeologists, cursed swashbucklers, super cool super spies or a looming carcharodon carcharias, the movie is made better because of its music.

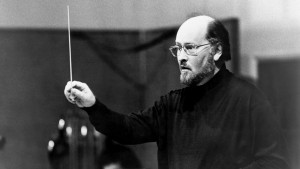

Of the featured composers in this concert one musician stands out more than the rest and that’s no surprise. He is a household name but who is John Williams? Should you ask anyone today you ‘ll likely get a range of answers but perhaps the simplest and most flattering opinion of the legendary and Juilliard-trained composer, conductor, orchestrator is Hans Zimmer’s answer, “John Williams [is] the greatest living composer — full stop.” But John Williams is more than a name; he’s the modern embodiment of film music and to say he’s an inspiration is a gross understatement.

A consummate professional, Williams carries the torch of the composers who have come before him. After all, he got his start at the end of that Golden Age, working as an orchestrator for Franz Waxman, Bernard Herrmann and Alfred Newman and as a studio pianist on film scores by Jerry Goldsmith, Elmer Bernstein and Henry Mancini.

He is known for being the best not only because of the magical music he writes but for what he gets out of the musicians under his supervision. Richard Kaufman, the Dallas Symphony’s Pops Conductor Laureate, in more than 10 years as a Los Angeles studio musician, played on five John Williams scores, including Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

“Working on sessions for John is unique, exciting, challenging, and always memorable. It’s very hard work because you want to do your best for him and the music he’s written. And what makes it so amazing…and different from most sessions with other composers…is the degree of respect and appreciation the musicians have for this great composer. And it’s not only an appreciation of the music, but of the man himself. One really has to be sitting in the orchestra on a John Williams session to know what it means to be part his musical vision, and experience the dignity and creativity he inspires in everyone around him.“

But what Williams and the others featured in this concert piece have done with their compositions is that they’ve nearly transcended the film medium. The respective works of Williams, Barry and Badelt far outweigh the story, plot and characters etc. More than a casual or arbitrary auditory attachment to the onscreen antics, these scores have become their own entities; they’re able to exist with and without you accompaniment of fantasy or truth to the narrative playing out on screen.

Whether it’s a suite, a march, or a concerto Williams’ music is one of a kind and easily recognizable. As William Shakespeare said, “Brevity is the soul of wit,” and it’s that sensibility and simplicity that endows the famous Shark Theme from Jaws (1975). Williams unleashes primal fear with two repeating notes. Jaws is remembered not simply for being an amazing piece of cinema (one that scared people out of the water for years), but also because it gave Williams the canvas on which to paint a modern high seas adventure and show the might and persistence of the world’s foremost oceanic predator. Those two notes are still instantly recognizable, simple music that telegraphs ominous approaching danger – and goes straight to the heart of the film’s story.

Barry, John Barry, and his soundtracks for the James Bond films set the standard for what fans expect in a spy film. If there’s a martini, a Bond girl and a gadget or two, the adventure is not complete without Barry’s musical accompaniment. Though Barry penned other great scores for Zulu, The Lion In Winter, Somewhere In Time and Dances With Wolves, it is his big, brassy, swaggering music to eleven James Bond films that most instantly resonates.

Famous title sequences set the tone for each and every Bond film, with theme songs performed by popular stars of the day, from Shirley Bassey (Goldfinger, 1964; Diamonds Are Forever, 1971; and Moonraker, 1979) and Tom Jones (Thunderball, 1965) to Duran Duran (A View to a Kill, 1985), Tina Turner (GoldenEye, 1995) and, most recently, Adele (Skyfall, 2012). Live and Let Die (1973) got a super shot of energy from Paul McCartney & Wings. Yet these symphonies of visuals by Maurice Binder would be nothing more than fancy montages without beefy compositions by Barry and others.

“Por una Cabeza”, is a tango with music and lyrics written in 1935 by Carlos Gardel and Alfredo Le Pera. Used in multiple films including True Lies its most famous modern use on the big screen is 1992’s Scent of A Woman. On many occasions, some of the most famous virtuoso musicians have performed for Hollywood and there’s the idea that they thought they “degraded themselves by taking Hollywood’s money…” so said Gene Shalit (while interviewing John Williams prior to Williams and Itzhak Perlman performing their own arrangement of the famous composition). Yet before Shalit could finish the sentence Williams responded “…and thereby reaching billions of people when they’re doing it“. Williams understands that film music allows musicians the grandest stage of all from on which to play music so why not seize that opportunity? After all it was Erich Korngold who said, “music is music whether it’s for the movie theater or the concert hall“.

Now it’s not just an issue of the composer writing a great theme for the film but sometimes writing a theme for great musicians, like Issac Stern for Fiddler on the Roof (for which Williams won an Oscar). In Schindler’s List Williams enlisted the help of Itzhak Perlman because he believed that the story required “the sort of ambiance that a great violinist could bring to it“.

It’s obvious that working in film requires a chameleon-like approach to move from story to story and cater to the needs of each picture. Whether the story is set in galaxy far far away or in crucial time in history Williams, Barry, and others provide stirring arrangements that show such reverence for each and every script.

William’s themes have such resonance and popularity with the audience such that they, as Ray Bradbury put it, “live lives outside of the projection room“. Films and music live off, and for, each other and retain their impact be it in the symphony or in a pair of ear buds. Simply put, good music is good music. Yet great and sweeping musical themes and compositions are meant to be presented in the grandest way possible.

William’s themes have such resonance and popularity with the audience such that they, as Ray Bradbury put it, “live lives outside of the projection room“. Films and music live off, and for, each other and retain their impact be it in the symphony or in a pair of ear buds. Simply put, good music is good music. Yet great and sweeping musical themes and compositions are meant to be presented in the grandest way possible.

While film music did not, as Bradbury hypothesized in a crazy scenario, come to exist as a cloned off extrusion from films, it has been enjoyed in multiplexes, including home theaters of varying size and quality, and played by orchestras sans the cinema eye for decades. Williams’ work with similarly versed and musically-minded filmmakers contributes to the impact and eventually the legacy of his work.

Film music is never created in a vacuum. Cultivating joint effort, creative energy and a healthy back-and-forth amongst a production’s creative team allows musical ideas to unfold during a necessary and critical development process. It’s no secret that Steven Spielberg and John Williams work well together – Williams has scored all but one of the remarkable run of films Spielberg has directed since 1974. “John has literally transformed and uplifted every film we’ve made together,” Spielberg has said.

One of the best stories about the success of their collaboration came out of Williams’s efforts in crafting the iconic “Raiders March,” the main theme of Raiders of the Lost Ark. Williams was torn between two variations of the march. It was Spielberg who simply asked why both versions couldn’t be used together. Perhaps it was prescience on Spielberg’s part or just a case of not wanting to let anything Williams came up with go to waste. Regardless that one suggestion helped make the adventures of Indiana Jones all the more indelible and iconic.

Writing music for film, be it drama, comedy, action or sci-fi all starts with the most essential goal of a composer – suit the needs of story, but stay out of its way. Yet in many respects Williams’ music tells the story and it is the visuals that support it…and that’s what makes him so great. Could you imagine Star Wars without Williams’ contributions? It could easily have been a forgettable sci-fi yarn but Williams’ tendency to over-score the picture makes anything we experience on screen that much grander. That’s what each of the composers featured in this concert have achieved.

Their music gets to the heart of the story without obviously manipulating the audience. Williams is Indiana Jones’ cracking whip, John Barry is the sassy big band swing that announces James Bond’s entrance, Klaus Badelt is the wind blowing through Jack Sparrow’s hair. Regardless of the setting, it’s a stirring composition which causes our hearts and pulses to race. All these classic film scores effortlessly evoke a sense of wonder, adventure, danger and excitement….even if you’ve never seen any of the films.

For more info about the performances and events like this at the Meyerson Symphony Center head over to the official website for the Dallas Symphony.

If you’re a fan of the above mentioned composers, click these links to listen to some impressive retrospective concerts similarly honoring the work and careers of John Williams and John Barry.