If Warm Bodies is a sly mockery of everything Stephanie Meyer started when she wrote Twilight and assisted in its transition from novel to screen, then what can we make of Beautiful Creatures? The lesson here, I think, is that not every post-Twilight YA movie will improve on the formula; in point of fact, some of them will wallow in it. Beautiful Creatures, lacking all of the heart and wit Levine brought to his own spin on the young adult blueprint, blithely tumbles into the latter category; it’s almost impossible to enjoy even on a trashy, so-bad-it’s-good level, though bless Jeremy Irons and Emma Thompson for trying to bring the film to that sort of plateau.

If Warm Bodies is a sly mockery of everything Stephanie Meyer started when she wrote Twilight and assisted in its transition from novel to screen, then what can we make of Beautiful Creatures? The lesson here, I think, is that not every post-Twilight YA movie will improve on the formula; in point of fact, some of them will wallow in it. Beautiful Creatures, lacking all of the heart and wit Levine brought to his own spin on the young adult blueprint, blithely tumbles into the latter category; it’s almost impossible to enjoy even on a trashy, so-bad-it’s-good level, though bless Jeremy Irons and Emma Thompson for trying to bring the film to that sort of plateau.

Of course, this isn’t their film. Beautiful Creatures belongs to Alden Ehrenreich and Alice Englert, two attractive young talents who I have less than zero familiarity with (though Ms. Englert does happen to be the daughter of director Jane Campion, one of the most under-celebrated women working in film today). That’s another lesson in and of itself: not every YA film will have the good fortune to feature a Jennifer Lawrence or even a Nicholas Hoult. Truthfully, I’m damning Ehrenreich and Englert with faint praise– they’re actually quite a screen pair, brimming with chemistry and their respective brands of charisma. Trouble is, they’re acting in service to a very, very poor film with few pleasures to offer even the jaded adults of the audience.

Beautiful Creatures anchors us to the fictitious South Carolina town of Gatlin by way of Ethan Wate (Ehrenreich), a charming, sweet, too-good-to-be-true teenager itching to break free of his home and go to college somewhere exotic, like New York. Ten minutes into the story, we can’t blame him at all; Gatlin epitomizes the most stereotypical visions of the sticks. One suspects that director Richard LaGravenese (yes, the same Richard LaGravenese who wrote The Ref and The Fisher King, among other greats) had a strong urge to just rename the place Hicksville, for all the subtlety with which he develops the place and its inhabitants. Gatlin’s the sort of place where To Kill a Mockingbird is considered a work of the devil, and where the belief is strongly held that Democrats, homosexuals, and all liberals should burn. The need to establish Alden’s backwater burg as a location worth getting away from is understandable, but Beautiful Creatures lays it on molasses-thick.

Before long, Ethan encounters Lena (Englert), the new girl in Gatlin. We can tell she’s new because she’s pale, she adorns herself in modest dress, and she’s not constantly praying to Jesus for aid against Satan. Plus, she shatters windows without lifting a finger. Yes, Lena’s arrival signals the beginnings of some odd happenings indeed, and Ethan can’t help but find himself drawn to her, if not for her enigmatic countenance then because she’s an avid reader like him. She has a secret, though: she’s actually a witch. (The school’s Christian fellowship at least gets that right.) Not the good kind or the bad kind, either, but the undecided kind. She doesn’t get to pick a side– Light or Dark– until her sixteenth birthday, and even then, the choice is going to be made for her through a process called the Claiming.

Romancing a teenage girl with magical powers she can’t readily control seems like a dangerous prospect, but Ethan sticks by her, and the adventure begins. I’ll admit that on paper, nothing about Beautiful Creatures is any more repulsive than what’s usually found in the synopsis of your average YA novel. Structurally, these stories all follow very similar molds; it’s difficult to hold their tropes against them, especially as a guy who loves bad action flicks and even worse slasher movies. Imagine my surprise when at the start, Beautiful Creatures actually manages a measure of beguilement, mostly in its two leads and, eventually, in the scenery-chewing of the aforementioned Mr. Irons and Ms. Thompson. It’s light, slight, airy stuff without much of an edge or anything resembling nuance or delicacy, but that’s fine– it doesn’t need to be either in order to be fun.

Irons and Thompson understand that, so as soon as they get introduced into Beautiful Creatures‘ plot, the film picks up even more hammy steam. They know what kind of picture they’re in, and they chow down on the material with gusto. Englert and Ehrenreich don’t really seem to care one way or another, but they also feel like they belong. If anything, it’s refreshing to see the male play the unsuspecting mortal while the young lady holds all the supernatural cards, but as Beautiful Creatures‘ conceits and turns are made clear, the reversal starts to feel like a novelty. Lena, unsure of how she’ll be categorized after her coming of age, is nearly as disempowered as Ethan.

That’s one of the film’s real problems: the rules that Lena and her family of witches and warlocks (their preferred nomenclature is “caster”) live by don’t make a whole lot of sense, and nor does their kinship. It’s a challenge even at the best of times to figure out how these characters are all related, or why men can choose to be Dark or Light but women can’t, or why either designation matters at all when expectations demand that good or bad, everybody has to sit down and behave civilly at dinner. The further Beautiful Creatures delves into its own mythology, the sillier it feels despite how seriously the film takes itself. Of course there’s more to Lena’s Claiming (and her potential as a caster) than meets the eye; of course Ethan and Lena are connected through the hackish, drama-robbing machinations of destiny.

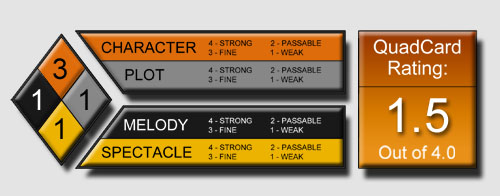

G-S-T Ruling:

As soon as Beautiful Creatures begins lumbering down the home stretch, we begin to yearn for those first thirty or so minutes where the magical hoopla still held mystery. Heavy-handed metaphors for adolescence, after all, can only be stretched so far. If the subtext to Lena’s plight makes sense, the amount of fate-based nonsense injected into said ordeal makes the rest of the film feel like a ridiculous, humorless slog. In any other circumstance, this would just render Beautiful Creatures “average”, but the film begins promisingly enough; that it ends so inexplicably is bitterly disappointing.