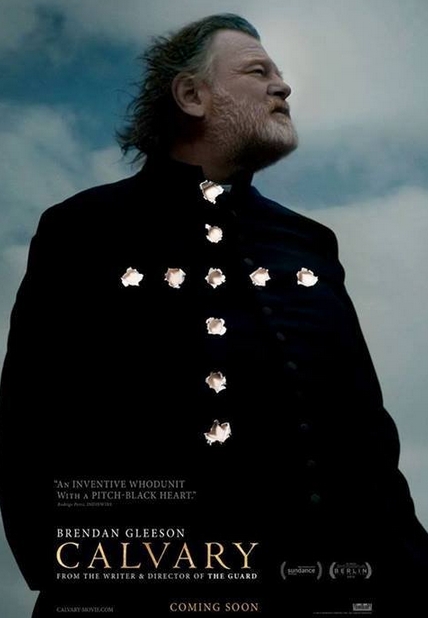

John Michael McDonagh’s film Calvary is a deeply emotional and moral character study that asks a lot of the audience. McDonagh, through the central character Father James (played by Brendan Gleeson), asks how (and why) would you continue to help others if, ultimately, they can be no help to you, especially in time of need. Beyond that, Father James learns, in a confessional booth no less, that his life is about to expire. His end will not be the cause of old age, or poor health, but murder. He even knows who will pull the trigger in a week’s time and so the film tells the story of the things he sets to do in the seven days he has left. He’s powerless to help save himself and therein lies the odd duality which finds him struggling with his obligation to the church and his religion even if doing so will send him to, quite literally, meet his maker.

John Michael McDonagh’s film Calvary is a deeply emotional and moral character study that asks a lot of the audience. McDonagh, through the central character Father James (played by Brendan Gleeson), asks how (and why) would you continue to help others if, ultimately, they can be no help to you, especially in time of need. Beyond that, Father James learns, in a confessional booth no less, that his life is about to expire. His end will not be the cause of old age, or poor health, but murder. He even knows who will pull the trigger in a week’s time and so the film tells the story of the things he sets to do in the seven days he has left. He’s powerless to help save himself and therein lies the odd duality which finds him struggling with his obligation to the church and his religion even if doing so will send him to, quite literally, meet his maker.

Calvary hinges on many characters. First and foremost is Father James’ daughter (played by Kelly Reilly) who, because of her own continually questionable mental and physical problems, has come to stay with her father. How does a priest have a daughter you ask? Well as the film explains, it is possible. The daughter of a relationship prior to his decision to join the clergy, Father James is not quite removed from people’s issues and problems (he’s lived parenthood before priesthood), he however as a  priest must find a way to distance himself and stay purely objective. It is Gleeson’s matter of fact delivery that makes the film feel so real. He really is interacting with an agnostic doctor, he really is dealing with a jaded bartender, he really is dealing with a removed and unethical banker, etc., etc.

priest must find a way to distance himself and stay purely objective. It is Gleeson’s matter of fact delivery that makes the film feel so real. He really is interacting with an agnostic doctor, he really is dealing with a jaded bartender, he really is dealing with a removed and unethical banker, etc., etc.

The film is a series of situations that finds each scene cutting to the core of an interaction. You won’t find people walking in or out of rooms, or establishing shots of locations, and this very nearly could exist as a play. What makes Calvary really interesting, beyond the timeless look and classical style of shooting, is that we following this character to his inevitable demise and yet never seem him waver. He doesn’t run away, he doesn’t call the cops, in fact he keeps the death threat to himself as he continues to deal with and, somewhat, accept the eccentricities and idiosyncrasies of every seemingly crazy person in his life.

It’s almost unbelievable, and yet at the same time hilarious, that so many people, all the characters in the story, can be so weird and colorful. What makes them more than superficial is the fact they are all damaged and they look to Father James for help. Some want it, some claim they don’t need it, but they all have problems they are wrestling with. There’s an almost surreal quality to the successive encounter. As Alice famously stated, each exchange between Father James and the citizens of the town are “curiouser and curiouser“. As they’re already at the end of their respective ropes, you get the feeling that each of these people would be completely helpless without Father James’ presence in their lives to keep them from completely losing it.

Of all the lines Gleeson gets to deliver, one seems the hardest to preach. Telling a younger priest that “You have to detach yourself from it. We are here to provide solace. Your personal feelings don’t come into it” we see it’s not that he struggles to give the advice, but more Gleeson’s struggle to believe in the words in the first place. Sure Father James is actively engaging these troubled people but, as a human being, can you truly remove compassion from your interactions because your profession demands it of you? Yielding to your job instead of your physiology is not an easy task. In a way McDonagh is touting the same message to us as if to say “get to know people despite their quirks and off-putting personalities”. Further these interactions offer an opportunity to constantly ask ourselves what we might do in each situation.

Not only is the writing razor sharp but it makes you think about issues on a multitude of levels. Everything from the questionable rationale behind joining the Army in non-war times, to the universal idea that “all souls are sacred” yet interestingly enough is that counterpoint that finds that some souls are less so. As a film, Calvary is also about forgiveness and letting go, in more than one sense of the word.

Much like a Western, in fact the classic High Noon is the film which McDonagh uses for inspiration (or “rips off” so he says in our interview), the townsfolk are equally troubled and struggling about a much as the central character. The rye twist is that we the audience don’t know who is out to get Father James. Yet as we meet them, and they take on a Stanley Kubrick style of quirk, we constantly wonder just who Father James will meet on a beach in a week’s time. It adds tension to every banal, or whimsical, or even hilarious exchange in this dark drama. The ‘whodunit’ phrase used in the pull quote is a bit misleading but the mystery of the shooter’s identity is just an added layer of interest in an already fascinating story.

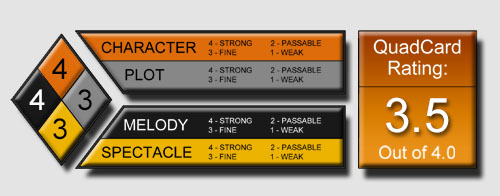

G-S-T RULING:

Even when you find out which character has it in for Father James Calvary warrants many more trips down the religious rabbit hole for you to experience the narrative on different and overlapping levels. This could be one of Brendan Gleeson’s best films to date. McDonagh gives him a canvas on which to paint a nearly career defining performance that is so subtle, save for some key scenes, some may overlook the brilliance in the simplicity in this portrait of such a interesting and equally damaged character.