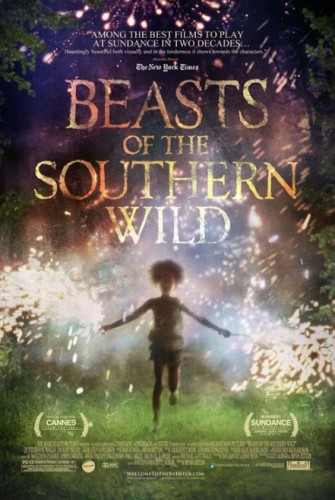

Benh Zeitlin‘s acclaimed Sundance and Cannes bayou fantasy hit Beasts of the Southern Wild is more than a unique exploration of familiar themes in extraordinary situations. It stands as one of the few current films sure to inspire formal discussion and wide-ranging opinions. Earlier this month I had the chance to sit down with the film’s two stars and director for a roundtable discussion and, below, you can find a talk with director Benh Zeitlin — it covers working with Quvenzhané Wallis, the affect of the BP oil spill on the set, difficulties in editing, favorite moments, and getting to work at Skywalker Sound.

Benh Zeitlin‘s acclaimed Sundance and Cannes bayou fantasy hit Beasts of the Southern Wild is more than a unique exploration of familiar themes in extraordinary situations. It stands as one of the few current films sure to inspire formal discussion and wide-ranging opinions. Earlier this month I had the chance to sit down with the film’s two stars and director for a roundtable discussion and, below, you can find a talk with director Benh Zeitlin — it covers working with Quvenzhané Wallis, the affect of the BP oil spill on the set, difficulties in editing, favorite moments, and getting to work at Skywalker Sound.

———————————————————————————————————————-

When dealing with this young cast — especially so many that haven’t acted before — did you try to get [star Quvenzhané Wallis] to come into the atmosphere, mood, and the setting, or did you just let that naturally progress and allow her to do her thing?

Benh Zeitlin: No, she was in training. Whether she remembers it, I don’t know. Or whether it seemed like training, I don’t know. We would have different things for her to do in pre-production; we had a long, long rehearsal process. My sister built the house where Wink lives in the movie, so I would send her back with my sister and they would hang out with the animals, and she would slowly get comfortable hanging out with the pig. Touching the pig. Holding a chicken, which isn’t something she normally does. We would put her inside boxes and have her draw things. We would have her and [Dwight] Henry cook meals together and get to know each other and bond in different ways. So there were all kinds of things we did that were sort of games that got her building relationships with the other characters and got her acclimated to the world of the movie.

She told us how she worked with you making changes in the script. When she started, how did she learn her lines?

She’s incredibly intelligent, as you guys can tell. But it was the biggest challenge, just retaining information. We had to redesign the script. If she was supposed to say a long line in sequence, a lot of times we would look at it at night, which is what she is talking about. I’d sit her at the computer, and we’d look at a line, and she’d say, ‘This line is too long. I need a break in the middle of this line.’

So then I’d think of something for someone else to say, at that moment, or some reason for us to cut away. We’d break it up in that way, and also if any words she didn’t recognize or phrases she didn’t think she would say, I’d let her change it and put it in her own words. And that process happened, really, for every single character in the film. But for her, I let her actually type because she was just learning how to type, so it was fun for her.

How did you come to this source material? How did you hear about the play and how did it evolve?

The play is by a friend of mine who I met while at a playwriting camp when I was 13 years old. It was sort of produced once, but mostly I knew it because I knew her work. She’d send me all her stories and plays and we were really close friends all of our lives. I was actually working on doing something with her work — separate from the idea of this film. Sometimes, as you work on things, you discover what you’re interested in because of commonalities. And I realized there was this thread between her story — which is about a little girl losing her father and the end of the world coming as that happens — and, then, my story, which was this group of holdouts in this community that was losing its place. So, it was that kind of similarity in the emotion between the two stories that made me realize that they should be told as one story. Her story became a way into a

vaguer concept of the film I wanted to make.

She lives in Georgia?

She’s from north Florida, but sometimes she says Georgia because it’s literally right over the border. It’s a lot more like Georgia than Florida.

So did you go there to work with her on the script?

We did that for one part. We stayed with her parents. Her father is a big inspiration for Wink and her animals are a big part of the inspiration for the animals in the movie. So I went out there for a couple of weeks, but I very quickly realized I wanted to make a picture about Louisiana, so one of the first things was translating that story into the geographic and cultural context of Louisiana.

So the main place we wrote the script was at the end of this marina way down a road in Louisiana. If you look at a map it just looks like marsh and water, but this road stretches all the way down, and there’s a marina at the end of it. So we had a room at that place, and we would write on the docks. When we’re writing, we’re casting, location scouting, and researching all at the same time. Things that we discover. Rewrite the script and modify the script so it’s sort of always evolving as we look for the elements that are going to be the movie.

The oil spill aspects: Is it just a coincidence that it was in there?

Well, we wrote the film three and a half years ago, and we started shooting two years ago, and the actual first day of photography was the same day as when Deep Water exploded. So it wasn’t something that was consciously in the script, initially, but it was this very visceral parallel that was happening as we shot. We shot largely in sequence, so as nature dies in the film, that was happening in the water. The town where we were was one of the closest places to Deep Water, if not the closest.

The marina I’m talking about, where we wrote the film, was taken over by BP as the base of their operations for the cleanup. Several of our locations were on the wrong side of the boom, so they were contaminated. We had to negotiate with BP to get out boats past the booms and into the areas we were planning to shoot. It’s one of those things that makes you feel like you’ve written a story that is real and important.

Life imitating art?

Yeah, life imitating art — or something like that.

Did that extend the shoot significantly?

It’s really interesting, because BP was in such deep shit that they were incredibly cooperative with anybody who wanted to do anything pro-community. It was really hard to get them to cooperate with us, because there’s a thousand people you need to talk to, but their whole mandate was to be the nicest guys you can imagine.

They didn’t double your budget?

No, they opened the booms for us; they let us through. It just was surreal. But, more than anything, it was an obstacle. We didn’t have to fight with BP to make the film or anything like that. But, for the town, there’s sort of a lag in the effect. But things are getting really bad, right now. We thought it was going to be bad immediately, but the last two fishing seasons have been the worst in their history. All that stuff is really coming home to roost right now. It’s pretty tragic.

You mentioned that this was one of your friend’s plays that you were brought up knowing. Hindsight is always going to be 20/20, but what kind of pressure did you have to put in this film from her work? Was it anything unique, because it was your friend? Or was it a good working relationship?

Oh, yeah. We fought about story elements and what we thought would happen and not — but it’s not like the film is an adaptation of the play. It’s really just inspired by the play. There’s no scene from the play that’s in the movie. It’s really the characters and the tone and the idea. So there was never a thing of ‘We have to keep this scene in.’ It was always going to be a total reinvention of what the source material was.

Being your first feature, is this your statement style or just the way that this film came about?

I hope my style is always evolving. I don’t ever want to get stuck on one thing, but I think it wasn’t an accident the way the film feels. I think we sort of think of this film as… not the culmination of something. We’ve sort of, as a group, developed a set of tools that are pretty different from the kind of tools you would use to make a film normally. Our production process is totally unconventional; largely out of inexperience, but also by believing in certain ways of going about production. So I think that we consider this the first — and we hope to make more films that are completely different — but with the same sort of principles and process.

Is there a favorite moment that you look forward to seeing over and over again?

There’s a few. I don’t know if anything was in the first draft that’s in the final draft; it was completely destroyed over and over again. There’s a couple things in it that you always try to explain on paper — and no one could ever understand why they were in the movie — but I held onto a couple. Probably my favorite is when the little girls swim to the floating brothel and kind of experience this heaven of mothers. It didn’t really make a lot of narrative sense. It’s all the things that don’t make narrative sense but make emotional sense. That was really the guiding principle of the structure of the film.

You can have an active movie, with lots of action. Things that are exploding or setting on fire, and beasts coming. All of these things that are sort of part of narrative cinema traditionally, but you didn’t need a plot-based structure. You could have an emotional structure. The development of her emotions and the development of her feelings would be what caused one event to follow the next one. I always felt like, at this moment in the film, when you get this sort of feminine love, that’s in such stark contrast to the male-dominated love of the rest of the film; it balances this movie in a way that I always felt was really satisfying.

He’s always like, ‘You’re the man’ to her.

Always, yeah. He’s teaching her the only way he knows how, which is how to be a man. The only way he knows how to survive is through muscle and grit and strength.

With such an organic pre-production and production, editing a film is a very secluded thing. Were they still involved at that point, or was it very much secluded, and did you miss that interaction?

Definitely. Yeah, I mean you, like, shrivel up in post-production. It’s a funny process. I get real pale and fat.

[Everyone laughs]

The film is this physical thing where you come out of it strong and weathered and you just kind of shrivel up. I mean, it took us two years to edit the film, so it was a long, long process. The editors don’t get as much credit as they’re due. As film with this amount of chaos embedded into the production, we don’t get everything we go after. You try to overcome all of these things but, sometimes, you make it and sometimes you don’t. So you end up with a script with holes in it. Lots of gaps in what you thought was going to be exposition.

It took a long time to get the film into her head. To get the subjectivity right, where you felt you were always experiencing things through her. So that process took an unbelievable amount of time and work. So, my two editors, Crockett Doob and Affonso Gonçalves, don’t get enough credit for bringing all of these rickety elements to this point where you can watch the film and never think about it.

Were there people in your life that were beacons for you growing up to want to do film, that shaped your creative life?

Kusturica. Emir Kusturica is this Serbian filmmaker that makes these kind of wild, gypsy, mystical adventure comedies, and I think that type of reality in my films is probably the most similar to his. Also, the type of production. You watch those films and there are animals running all over the place; I remember seeing 300 geese running across screen. There’s just this chaos about it that both looked like something I wanted to do and, aesthetically, but also wanted to do on a personal level. It looked like so much fun and an adventure to make those films. So that was a huge inspiration for me.

And then I’m just a movie addict. Stuff from when I was born… I grew up on Disney movies and watched The Princess Bride 300 times and Willow like 180 times. I have astounding viewcounts on every VHS tape that was ever in my house. And I love film from all eras and all types of high art film and lowbrow film. I don’t really make distinctions between them and I always feel like this film is a real mix between a more lyrical type of cinema and the dumbest AMC Palace stuff that I love going to see every weekend.

So was it fun, having your own pre-historic beasts in this one?

Oh, yeah. We also developed the sound at Skywalker [Sound], so we’ve hidden some sounds from Jurassic Park inside of the movie. Yeah, that footstep is in there — you can search for it. And people always ask if it was an add-on, but it was always embedded in the fabric of the film. You kind of get a first couple of key images when you realize ‘I’m going to make this movie.’ Her staring down that beast was always… that was the poster, to me. ‘This is what this film is somehow about.’ A lot of it, you sort of backtrack out of it. What is it about this image? What does this image mean? Getting to create those things.

The special effects are all archaic. It’s almost all practical, with the exception of some green screen stuff at the end. But nothing is CGIed or animated. You get to go back and read about Terry Gilliam movies, and how they did the miniatures and building cloud tanks based on photos. We get to relive the ’80s and ’90s ILM world in our little garage that we made the film in.

Any upcoming projects you’re going to do or ones you want to tackle?

Yeah, the next film I’m going to do is going to be the next of these movies, basically. It will be hopefully bigger and better. But the same people, same production. Hopefully we can use a lot of the same cast. It’ll come from the same world, but it will be a new story. But another big, epic folk tale that’s built by hand.

Coming from Sundance and then Cannes — and having such critical success and praise, but not yet having a release — are you being given more money or more opportunities just based on that? Or are you still working and building in that direction?

[Laughs] Well, I’m still shoving all the free food in my pockets.

[Everyone laughs]

Certainly there’s opportunities to go direct Final Destination 7 if I wanted to, but I don’t. But the exciting thing is that it is going to give us… if no one had ever seen this film, I don’t know if we could have gone and done this again. You use up every favor that you have making a film like this. I think this will be something that allows us to do it again, and we can leverage to protect the method and be able to feed ourselves while we do it next time.

Beasts of the Southern Wild is now playing in limited release.