A bit of a foreword for Go, See, Talk! viewers who are unfamiliar with the Criterion Files: I started this series over at A Constant Visual Feast back in February of this year as a way of covering older ground as well as some contemporary territory in cinema by delving into the massive and varied assortment of films gathered together in the much-vaunted Criterion Collection. In each Files entry, I’ll talk about two different Criterion releases– not necessarily connected by anything other than bearing the Criterion seal of approval– speaking to the films themselves and possibly their contexts and positions in film history. Think of it as me doing my homework, only far more entertaining and satisfying.

——————————————————————————————————————————-

So, let’s not waste another moment here. In the GST inaugural edition of The Criterion Files, today we’ll be examining Roman Polanski’s Cul-de-Sac (1966) and Whit Stillman’s Metropolitan (1990), which play like night and day to one another. The former represents a dark comedy of the absurd, fraught with sexual politics, games, and frustrations; the latter, a relentlessly well-read vision of the haute monde, punctuated by gracefully static camerawork and dialogue constructed with grandiose formality. Arguably, matters of class could make these films immeasurably distant cousins, but their concerns and timbres differ too drastically for any such relationship to be anything more than superficial.

So, let’s not waste another moment here. In the GST inaugural edition of The Criterion Files, today we’ll be examining Roman Polanski’s Cul-de-Sac (1966) and Whit Stillman’s Metropolitan (1990), which play like night and day to one another. The former represents a dark comedy of the absurd, fraught with sexual politics, games, and frustrations; the latter, a relentlessly well-read vision of the haute monde, punctuated by gracefully static camerawork and dialogue constructed with grandiose formality. Arguably, matters of class could make these films immeasurably distant cousins, but their concerns and timbres differ too drastically for any such relationship to be anything more than superficial.

Fittingly enough, our first film, Metropolitan, drenches itself in that sort of shallowness that while maintaining an undercurrent of substance, creating something of a modern take on the Jane Austen novels (though Stillman’s hero represents someone closer to an F. Scott Fitzgerald-type more than anyone else) which it so frequently recalls and dissects. The film depicts the activities of children of old money, a group of young adults enjoying the benefits of monetary security by birth; throughout most of Metropolitan, these kids spend most of their free time either going to debutante balls or fussily preparing for them, and afterward engage in endurance rounds of intellectual discourse (which provide the greater part of the film’s settings).

There’s a strong temptation to describe these characters as nothing more than bored and hopelessly vain twenty-somethings, but I think that’s somewhat disingenuous. Such a description discounts the better merits of the film’s more prominent players– the quiet, old-fashioned Audrey, the incorrigible, self-aware Nick, and of course Tom, initially an unwilling participant in the debutante world and an outsider despite hailing from a moneyed background himself. Tom brings wide-eyed idealism to the group of eight young people Stillman introduces us to, as well as worldly inexperience and the ill-informed presumptions of youth; he doesn’t read books, but instead reads literary criticism as a means of killing two birds with one stone. He’s an essential force in the group dynamic, serving as the catalyst for the film’s plot and as a means of reflecting the self-absorption displayed by the people he interacts with throughout the course of the film.

That element of selfishness acts as something of a preservative for Metropolitan, keeping it remarkably fresh and relevant more than a decade after its release. In time, our group of uptight, philosophizing bon vivants run afoul of Rick Von Sloneker, a man so callously enamored of himself and indifferent to others that he makes our principals look charitable and altruistic by comparison. No character in Metropolitan falls outside of the 1%, but on that token, no character better symbolizes the 1% of today better than Von Sloneker, whose appearance and attitudes loudly proclaim his outrageous wealth and sense of entitlement; today in 2012, it’s not hard to see this utterly offensive character, minor though he may be, as the blueprint for the new money of today.

As a representative of that culture, Von Sloneker possesses so little appeal that I must ask myself if I missed an opportunity to be coy with this installment of the Criterion Files. Should I have paired Metropolitan with The Discrete Charm of the Bourgeois? The Bunuel film is, after all, referenced very directly by one of Stillman’s more pedantic and irritating characters, Charlie, a bespectacled young man who so obsessively opines the imminent decline of the upper class (which he dubs “urban haute bourgeois“, or “U.H.B” for short) that I rather think he anticipates that oft-mentioned class “doom” with a perverse sort of glee. Charlie, of course, misses the point; the lifestyle of the U.H.B. has allure, but not necessarily charm.

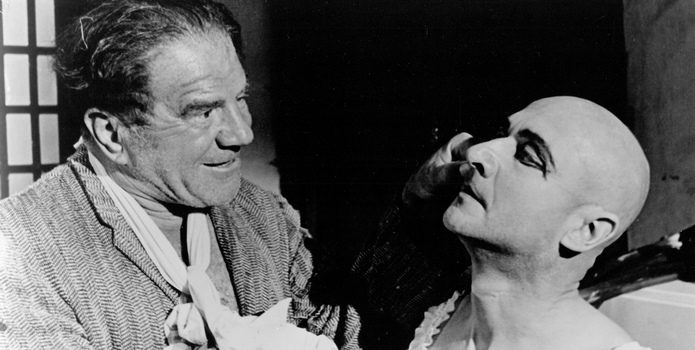

That’s a characteristic which Dickie, one-third of Cul-de-sac‘s primary cast, lacks. He’s such a boorish brute (or a brutish boor) that he almost deserves applause; after a time, his thuggish single-mindedness very nearly becomes endearing. Dickie’s on the run after a failed robbery, dragging his mortally wounded compatriot Albie in tow, but as we meet them their luck’s turning around. By chance, the two would-be crooks– unexpectedly cut off from the mainland by high tide– stumble upon a castle that serves as home to George and his much younger wife Teresa, who play unwilling hosts to Dickie and Albie while they wait out the night in anticipation of being rescued by their boss, Katelbach.

Cul-de-sac doesn’t bother structuring itself around a focal character, instead using the trio of George, Teresa, and Dickie as its joint protagonists. If anything, Dickie serves as the most central figure in the film; the entire narrative is driven by and revolves around his actions. Without him, Cul-de-sac never happens. At the same time, he’s a criminal, a real bear of a human being despite his bouts of childlike defensiveness, but he’s in fine company since neither George nor Teresa are particularly likable, either.

Therein lies the darkness at the heart of Cul-de-sac‘s humor. George, a neurotic milquetoast of a man, can’t stand up to Dickie and defend his wife from Dickie’s threats; Teresa, flighty and irresponsible, demeans and humiliates George while antagonizing Dickie at nearly every turn; and of course, Dickie’s a vulgar ruffian. Put them all together in one room (well, castle) for 111 minutes, and watch their personalities clash as Polanski uses their circumstances to examine the sadomasochistic sexual politics of George and Teresa’s marriage.

What ensues is at turns unsettling, uncomfortable to watch, blackly, bitterly funny, and ruthlessly absurd. For those familiar with Polanski’s body of work, Cul-de-sac (which the director once declared his favorite of his own films) is an echo of ideas and themes previously explored in the rest of his cinema; it’s likely no mistake that the leads of Cul-de-sac share a similar dynamic to that of the leads in Knife in the Water, a film released four years prior which also focused on an older man, his younger wife, and their interaction with a stranger who usurps the husband’s power. Arguably the only difference between the two lies in how Teresa and Dickie treat one another, but regardless all of the same themes present in Knife rear their heads here as well, sealing them as essential interests in Polanski’s career.