For roughly half of my life, I have been a died-in-the-wool J.R.R. Tolkien fan and a frequent visitor to the fantasy realm of Middle Earth. I’ve read each of Tolkien’s significant works which take place in that fantasy world– The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings novels, and The Silmarillion— several dozen times in total, and I’ve seen each of the films based on the Rings books numerous times in theaters. (True story: I watched The Two Towers thirteen times in its theatrical run. I am capable of being that guy.) When China Miéville described Tolkien as, “the wen on the arse of fantasy

For roughly half of my life, I have been a died-in-the-wool J.R.R. Tolkien fan and a frequent visitor to the fantasy realm of Middle Earth. I’ve read each of Tolkien’s significant works which take place in that fantasy world– The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings novels, and The Silmarillion— several dozen times in total, and I’ve seen each of the films based on the Rings books numerous times in theaters. (True story: I watched The Two Towers thirteen times in its theatrical run. I am capable of being that guy.) When China Miéville described Tolkien as, “the wen on the arse of fantasy  literature”, I felt a sudden need to take a pin to his head so as to deflate his absurdly over-inflated sense of importance and ego*. Some geeks love Gene Roddenberry; others, George Lucas; others still, Stan Lee. I lay my allegiance at the throne of Tolkien.

literature”, I felt a sudden need to take a pin to his head so as to deflate his absurdly over-inflated sense of importance and ego*. Some geeks love Gene Roddenberry; others, George Lucas; others still, Stan Lee. I lay my allegiance at the throne of Tolkien.

I’m telling you all of this in the interest of full disclosure. When I talk about the various degrees of backlash facing Peter Jackson’s film adaptation of The Hobbit, which is just two weeks away from release, you deserve to know without a shadow of a doubt that I do in fact have a dog in this fight. That dog happens to be the precursor to one of the best fantasy stories set to celluloid nearly a decade ago as well as their literary primogenitors. Put another way, I have a very clear bias, and it’s important that you know as much so that you may make the conscious choice to take my words here well-salted. Leave it to a loyal Rings fan to come to the aid of that rarest of creatures: a big-scale studio blockbuster in desperate need of defending**.

If any such contemporary picture needed a champion, though, it’s certainly The Hobbit— and in fact, the entire planned trilogy of Hobbit films. There’s been a degree of unrest floating around the project for some time, but the most recent kerfuffle over claims of animal cruelty on the set have given other complaints about the series a chance to crystallize. Concerns abound over the fact that Jackson and New Line will tell the tale of Bilbo Baggins in three films rather than two, as originally stated when the film was first announced, as well as the use of new technology called “High Frame Rate 3D (HFR 3D)”, which runs at 48 FPS– twice that of conventional movie frame rates. While I think it’s fair to write off that first issue as nothing more than an attempt to garner free publicity and undeserved attention on the accusers’ behalf, questions of format and scope demand a great deal more of our effort and energy to confront satisfactorily– which makes both the strong outcry against the three-film structure and the use of HFR tech feel frustratingly preemptive.

Not to say I don’t understand the reservations held against one element or the other. I’m familiar with the sort of aesthetic HFR 3D allegedly lends to a picture– that natural, smooth sense of movement, that fluid visual rhythm. Watch any standard soap opera and you’ll see a version of the effect yourself (or most any British television program, a’la Torchwood); it’s a reduction in the qualities that make American TV shows look so cinematic. Of course, the effect of watching The Hobbit in HFR 3D on a big screen will be far more dramatic than anything you’ll find on TV, so watching an episode of Dr. Who or three or four likely won’t serve to fully prepare you for what’s surely going to be far, far more noticeable in Jackson’s film. Put in simpler terms, I get the resistance to the presentation; it’s very much unlike what we’re accustomed to in our cinematic diet.

I’m also sympathetic to fears that stretching The Hobbit— a book that clocks in at a trim 310 pages–into a trio of separate movies could damage the integrity of Tolkien’s story. That kind of approach makes much more sense at first blush when used in adapting something like The Lord of the Rings, an epic yarn about good, evil, a smorgasbord of battles and skirmishes, talking trees, elves, orcs, kings, friendship, and loyalty told over three novels that each range between 400 and 600 pages apiece; meanwhile The Hobbit enjoys a more minute page length and also tells a far more close-knit, intimate story about one person’s (well, hobbit’s) journey toward self-confidence in which he broadens his horizons and opens himself up to a world he previously had zero experience with. Yes, yes, there’s a dragon, and a man who shapeshifts into a bear, and goblins galore, but there’s no denying that The Hobbit resides within a micro plane rather than a macro plane.

And yet the hand-wringing over Jackson’s treatment of the text reads as exceptionally reactionary, the HFR criticisms in particular because they’re so much more superficial. Let’s recall 2009, back when 3D really began trending in blockbusters and the sky began its slow descent; since then, many of us have adopted the practice of entirely skipping 3D releases for their 2D variants, unless audience and/or critical response tells us to behave otherwise (as in the case of films like Avatar, Hugo, and Coraline) If we can make the decision to ignore the 3D presentation in favor of the 2D, with noted exceptions, we can make the same choices with HFR 3D and The Hobbit, which will screen in regular 2D formats too. In blunter terms, if HFR 3D isn’t your cup of tea, don’t pay to see The Hobbit in HFR 3D.

Audiences and film enthusiasts often find a way to make a mountain out of a molehill when it comes to matters of presentation– for example, arguments and discussions about the merits of other non-traditional formats like IMAX are still ongoing even with the passage of time and the slow acclimation to its effects. So the devious case of the HFR 3D format represents more of the same, and to an extent all wariness over unconventional film formats makes sense. Audiences are universally used to watching films one way. When filmmakers strive to reshape or outright shatter the standard mold, we historically tend toward caution and defensiveness. Once upon a time, cinema-goers were perfectly content with silent, black and white films; fast forward to the present, and silent films are non-existent while black and white films are very, very rare (and forget movies that are both silent and black and white, save for The Artist, a pure nostalgia picture). We were of change, but change happened anyways. Such is the case with The Hobbit, though today we also have the luxury of being able to choose between the old and the new***, and the existence of choice puts criticisms of HFR 3D into a less defensible light.

The greater point of contention, then, is Jackson’s and New Line’s decision to sunder Tolkien’s single novel into a trilogy of films. As a Jackson supporter, my knee-jerk reaction is to say, “sack up and deal with it’, but knee-jerk reactions hardly make for good, valid criticism and rarely if ever provide positive contributions to a debate. And the truth, of course, is that admirers of Tolkien’s book have a few very real reasons to worry over three-part Hobbit film, though I imagine that the most tangible reasons represent the least explored in most discussions on the subject. How does one go about inflating such a lean text to suit a three-film structure? And to what purpose?

The implication is one of avarice: make more movies, earn more money****. Frankly, this sort of accusation is hard to deflect; money drives everything in Hollywood, so it’s impossible to argue with a straight face that nobody at the studio had dollar signs cavorting through their heads at the mere suggestion that The Hobbit could be split into three films. Yes, the decision likely was motivated by revenue, but that doesn’t mean the bottom line has more influence over the production than Jackson himself, who looks lively and ecstatic and energetic in each of his appearances in the Hobbit video production diaries. Compare the Jackson we see here– animated, cheerful, enthusiastic– to the Jackson of the King Kong production diaries from seven years past– worn down, burnt out, simply exhausted. Just as he was with The Lord of the Rings, Jackson is the key to The Hobbit‘s success; it will live or die on his conviction and his zeal. Perhaps the sight of a charged-up Jackson isn’t a surefire sign that the film will be any good, but it’s encouraging nonetheless.

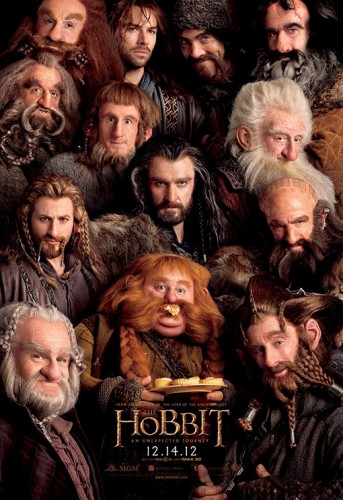

Which brings us to matters of length. Yes, The Hobbit is utterly miniscule compared to The Lord of the Rings; even on an individual basis, the book is still smaller than any single entry in that entire epic. The idea that three hundred pages of writing could be expanded not simply into three films, but three films that will run at just shy of three hours each, stretches credulity, but it should be noted that Tolkien isn’t a man well-noted for his brevity. He can spend as much time describing a hobbit-hole as a massive battle between nearly a half dozen armies. In a way, his work is extremely cinematic by virtue of being so detailed and descriptive and it lends itself to extrapolation because it’s set in such a vivid fantasy world populated by rich fantasy characters. In short, three hours gives a great deal of room for Jackson to let the story, the cast, and the settings breathe, and given that the world-building and character development were the two best qualities of the Rings pictures, this should only be seen as a good thing, especially given the inclusion of veteran Rings players (McKellen, Blanchett, Weaving, Serkis) and the overall depth of talent in the rest of the cast, from Martin Freeman to Richard Armitage.

That’s to say nothing of the appendices, either. There were degrees of hemming and also hawing over whether the trio of Hobbit movies would be fleshed out with the introduction of material from The Silmarillion; while Jackson never managed to snag the rights to that tome, he did acquire rights to some of the appendices, which should only be taken as a good thing. From previews we already know that Saruman appears in the first picture, presumably to convene with Gandalf, Galadriel, and Elrond to discuss assaulting Dol Guldur; we’ve also seen snippets of what looks like moments from the War of the Dwarves and Orcs in the most recent TV spot, and all of this is in addition to the stuff that comes right off the pages of the book, too. Consider what’s been displayed in trailers and teasers– much of it involves dwarves and introductions, with moments from the goblin tunnels. While it’s not certain where the first installment will end, that still represents a microcosm of its content in totality. It might be odd to see The Hobbit cut into thirds, but that doesn’t necessitate immediate negative perceptions of the first movie before it’s even screened for critics.

It’s much more odd for The Hobbit to be in the position of nearly being an underdog with mere weeks until it hits theaters. Several years ago, there was an atmosphere of excitement at the prospect of PJ returning to the Middle Earth cinematic sandbox once more to complete the story of the One Ring for good and all. With Guillermo Del Toro’s departure from the project, the addition of the third movie, and the constant hyping of the HFR 3D format, what feels like a large percentage of that initial goodwill seems to have turned to scorn. Maybe there’s a dash of iconoclasm to the sudden turnaround, or maybe people are genuinely anxious that Jackson won’t be able to maintain continuity between The Hobbit and his Rings films; whatever the case may be, there’s more reason to be excited for the picture’s impending arrival in theaters than not .

*Hey, the guy can write. I like Kraken and Perdido Street Station, even if the latter gets pathetically self-indulgent for very long stretches and has more fat than a season of The Biggest Loser. But Miéville’s pompous audacity never fails to leave me awestruck.

**Because look: most blockbusters really don’t need anyone to stick up for them. The really bad ones (Battleship) fail miserably as they deserve, while the higher quality but more contentious ones (The Avengers, The Dark Knight Rises) make money hand over fist despite receiving their share of criticisms. That’s because they’re designed to succeed and generate revenue. They generally don’t need to be defended outside the context of their content. Realistically The Hobbit is probably going to make a kajillion dollars no matter what, but I can’t think of a single spectacle film this year that has had to suffer anywhere as much bad publicity over production-based concerns. Admittedly, yes, maybe Cloud Atlas needed some defending too, but The Hobbit hasn’t even screened for most critics yet and people are boycotting it.

***For now anyways. Maybe someday we won’t.

****And if you hold this against The Hobbit, you have to hold it against Harry Potter, The Hunger Games, and Twilight. Not that anyone needs motivation to pile abuse on Twilight.