If Jackie Robinson’s fate had seen him turn out an unsung hero, 42 might be more worthy of protest. Taken at face value, it’s strictly inoffensive; it’s the tale of how Jackie Robinson broke the glass ceiling in baseball, diluted into a series of uplifting bullet points before coming to an abrupt and all-too-convenient close (because nobody wants to end a feel-good movie with reality). There’s a blueprint to this sort of cinema, and Brian Helgeland follows it doggedly in his third- technically fourth, if you count Payback*- directorial outing, hitting beat after crowd-pleasing, expected beat. Maybe that’s not a crime worthy of filmmaker jail, but it’s certainly not a guaranteed path to great, memorable cinema.

And Robinson’s story should be precisely that: memorable, gripping, and resonant. It probably bears mentioning that 42 hardly marks the first time the entertainment biz has had the bright idea to commit his struggle to celluloid; David Alan Grier and Andre Braugher (among several others) have portrayed him in Broadway shows and TV films dating back to the 80s and 90s, respectively, and over half a century ago Robinson starred as himself in a 1950 biographical picture. What Helgeland had here was a chance to make the definitive Jackie Robinson film, an opus standing head and shoulders above all its predecessors and a monumental reminder of the man’s inspirational impact and cultural importance.

And Robinson’s story should be precisely that: memorable, gripping, and resonant. It probably bears mentioning that 42 hardly marks the first time the entertainment biz has had the bright idea to commit his struggle to celluloid; David Alan Grier and Andre Braugher (among several others) have portrayed him in Broadway shows and TV films dating back to the 80s and 90s, respectively, and over half a century ago Robinson starred as himself in a 1950 biographical picture. What Helgeland had here was a chance to make the definitive Jackie Robinson film, an opus standing head and shoulders above all its predecessors and a monumental reminder of the man’s inspirational impact and cultural importance.

Which makes his failure to do so sting all the more. It’s possible, but improbable, that that film already exists in the annals of cinema, but little is more frustrating than the sight of an opportunity squandered. 42 takes us from Robinson’s time in the Negro leagues to his rise into the Minors and, eventually, the Majors while documenting the resistance and outright hatred he ran into along the way; it’s a narrative interwoven with the efforts made by a cadre of white people to protect him nurture him along the way, so much so that at points it feels like Helgeland almost wants us to empathize less with Robinson himself more with his Caucasian guardians. Helgeland doesn’t whitewash, but he does mix up his priorities here and there.

Admittedly, that’s a nitpick. We might never have known Robinson’s name without the efforts of men like Leo Durocher, Pee-Wee Reese, and, most of all, Branch Rickey, but they’re supporting characters. We’re not here for their story. Durocher, here perfectly embodied by the too-rarely-seen Christopher Meloni, at least gets ejected halfway through the film (though Helgeland fudges the facts behind his suspension, swapping real-life scandals for dramatic effect); he contributes, and then he’s gone. Rickey’s more of a presence, sauntering into frame and giving Robinson a spirited pep talk before the plot lurches forward once more. More than once, Jackie threatens to become a minor figure in his own movie.

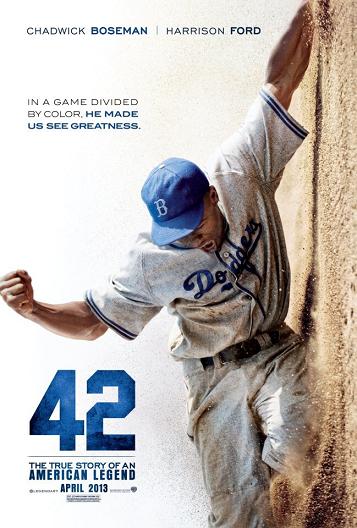

It’s a blessing, then, that Helgeland found a good leading man to give the role some vitality and authority. You probably aren’t familiar with Chadwick Boseman- he has one other film credit to his name, 2008’s The Express, and has mostly appeared in one-offs on television (save for the unfortunate Persons Unknown, which he committed thirteen episodes worth of his time to). That’s a good thing, though. Like Robinson, Boseman’s a rookie with something to prove, and though the stakes are astronomically different for actor and subject, it’s easy to wonder if he used that as motivation in his performance. The short version: the kid’s good, energetic and charismatic enough to maintain his visibility in the forefront.

He’s held up by a number of random cameos and supporting performances- Hamish Linklater, Lucas Black, Alan Tudyk (in a role that makes him unlikable for once), the aforementioned Meloni, Toby Huss, Andre Holland, John C. McGinley- but he shares the most screen time with Harrison Ford and Nicole Beharie. Beharie plays Rachel Robinson (nee Isum); Ford brings Branch Rickey to life, but to think of these performances in the same fashion would be a mistake. Beharie has a strength and a charisma to her that makes it easy for us to see why Jackie loves her- she’s playing with earnestness, vulnerability and even bravery, here, fighting the fight for equality and the cessation of bigotry as much as her husband does.

Ford, on the other hand, sketches himself like a cartoon character, which he can get away with because he’s Harrison Ford. Nothing he does here jibes with the sort of honesty a biopic should shoot for- he’s over-the-top in the truest sense of the phrase. His face entire trembles and quivers with melodramatic energy in every single one of his scenes; he looks like he’s having a jowl movement. It’s to his benefit that Helgeland isn’t on the authenticity wavelength, either. In a more genuine attempt to articulate Robinson’s travails and triumphs on screen, Ford would throw off the entire production, but that’s not the sort of film 42 is, so his histrionics give the movie a measure of oomph.

G-S-T Ruling:

None of that is to say that 42 shouldn’t have aspired to be something better than what it is. Robinson’s influence doesn’t begin in 1945 and end in 1947 with the Dodgers winning the National League title; the film tells us that he went on to be named the very first Rookie of the Year in a post-script montage, but we don’t see that, or witness his World Series victory in 1955. (And you can forget about a single mention of his involvement in the Paul Robeson Congressional hearings in 1949, which were, in short, a pretty damn big deal.) Can we go back to the 1990s and rally behind Spike Lee’s attempt to craft a more truthful cinematic rendition of Robinson’s life? Maybe box office success for 42 will spur him to revisit that failed project, but in the meantime, what we’re left with is saccharine, cheesy fakery that doesn’t do enough to honor Robinson and his legacy.

*You probably don’t.