If A Late Quartet, the second feature by Yaron Zilberman and his first film since his 2004 documentary Watermarks, proves anything, it’s that good performances can elevate average movies. To say that Zilberman’s cast saves his picture would be somewhat generous, though. They only distract us from its inadequacies, which are numerous, though perhaps this is a harsher judgment than the film really deserves. A Late Quartet is harmless, airy fluff, small-scale prestige cinema that smartly gathers together a group of very gifted actors in the service of exploring life lessons filtered through the overarching motif of Beethoven’s Opus 131 String Quartet (in C-sharp minor); it’s also painfully undercooked to the point of being nearly unpalatable.

So in this culinary metaphor, consider Phillip Seymour Hoffman, Catherine Keener, Christopher Walken, Mark Ivanir, and Imogen Poots the seasoning that helps mask the aggressive mediocrity of the whole meal. They’re at the center of A Late Quartet‘s dramatics, which revolve around the sudden and emotional turmoil experienced by the members of a veteran world-renowned string quartet when their cellist, Peter (Walken), announces that he’s been diagnosed with Parkinson’s as the group prepares for an upcoming performance of that aforementioned masterpiece. His declaration, made with quiet dignity, has gravity and power, yet for all the celerity with which the others– husband and wife duo Robert and Juliete Gelbart (Hoffman and Keener respectively), and Daniel (Ivanir)– ease into turning on one another, it’s not hard to assume that just about any garden variety stresses might have set them off.

So in this culinary metaphor, consider Phillip Seymour Hoffman, Catherine Keener, Christopher Walken, Mark Ivanir, and Imogen Poots the seasoning that helps mask the aggressive mediocrity of the whole meal. They’re at the center of A Late Quartet‘s dramatics, which revolve around the sudden and emotional turmoil experienced by the members of a veteran world-renowned string quartet when their cellist, Peter (Walken), announces that he’s been diagnosed with Parkinson’s as the group prepares for an upcoming performance of that aforementioned masterpiece. His declaration, made with quiet dignity, has gravity and power, yet for all the celerity with which the others– husband and wife duo Robert and Juliete Gelbart (Hoffman and Keener respectively), and Daniel (Ivanir)– ease into turning on one another, it’s not hard to assume that just about any garden variety stresses might have set them off.

That’s one of A Late Quartet‘s pratfalls– it’s drama for drama’s sake. Put more accurately, the conflicts that immediately surface following Peter’s heartfelt revelation occur inorganically. They happen only because the film demands that they happen. In a sense, this is true of any film, but good films are engineered so that their events play naturally and without calling to attention the grand illusion of the cinema. When Daniel, Juliette, and Robert step outside onto a snowy New York sidewalk, their bickering begins in earnest almost immediately and with jarring abruptness.

Of course, Zilberman has an answer for that. Everything that comes bubbling– well, roiling– to the surface after the opening scene, we quickly learn, has been simmering for a long, long time– Robert is jealous of Daniel, the first chair in the quartet, and sick of playing second fiddle to him (well, violin) as Robert is convinced he’s just as talented and more passionate than his soloist counterpart. Juliette’s marriage to Robert, meanwhile, is something of a mess; she neither regards him as highly nor loves him as much as he thinks she should, and the rift between them has set her in opposition to Alex (Poots), their daughter, who’s following in mom and dad’s footsteps as a violinist. Rounding things out, Daniel, the rigid perfectionist, is having an affair with Alex behind her parents’ back. Meanwhile, Peter has zero knowledge of any of this– but how could he? He spends most of the film off-screen.

Peter’s absence in the bulk of the film’s story reads as a puzzle. If A Late Quartet is meant to offer us insight into his story, then Zilberman fails in that area; if instead Peter is meant to serve as nothing more than the character who initiates plot and introduces conflict, then there’s still a piece of him missing that’s necessary for us to understand why his illness and his eventual departure from the quartet has opened up the doors for all of this infighting to occur. Juliette sees Peter as a father figure, and we can understand her ennui. But the scuffling between Daniel and Robert lacks any such connection, so Peter after a point stops being a character and instead comes to represent the cork keeping the wine bottled up.

Which makes him a much less interesting character, something Zilberman likely didn’t intend. Peter is the progenitor of all of A Late Quartet‘s strife; that he gets shuffled off to the side so often makes little sense, especially in consideration of the life-altering nature of the news he receives at the start of the film. Zilberman sets his story up as one about a man coming to terms with his descent into obsolescence and facing the inevitability that we learn has accompanied him throughout his tenure as the quartet’s cellist. Immediately, though, Peter becomes very nearly discarded in favor of sudden, artificial, selfish melodrama. There’s a good story to be found in the grudges and grievances the rest of the musicians bear, too, but it’s a story that isn’t at all given appropriate time to brew and develop.

So Zilberman’s cast is something of a blessing to him. While the material accorded them is thinly supported, Hoffman, Ivanir, Keener, Walken, and Poots– along with secondaries like Wallace Shawn– work tirelessly to mine their characters and their situations for value. In a better-plotted movie, the experience of watching these actors breathe life into their portrayals of half-written people would amount to something more substantial; in actuality, A Late Quartet presents its principals as so two-dimensional that its performers can really only play within a limited sandbox. They do so ably, but the result of their confinement is that their work can only numb the sting of the film’s flaws.

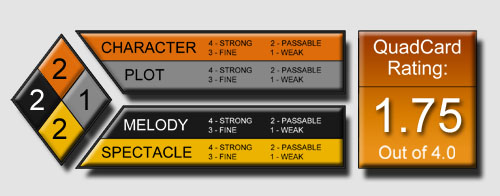

G-S-T Ruling:

Had there been more room for them to maneuver, though , A Late Quartet‘s collection of performances might have added up to more than merciful diversions from its warts. Regrettably, Zilberman never manages to pull his story together with coherency, giving the effect that the final cut was at one point or another mangled in the editing room; unlike the integral classical composition it is allegedly structured to reflect, A Late Quartet is ultimately disharmonious and dangerously condensed.