There’s nothing worse than reviewing a mediocre film made up of a trio of elements I actually like. In that respect, Black Nativity is a compressed version of my personal hell; it’s helmed by Kasi Lemmons, the gifted director behind such treasures as Talk to Me and Eve’s Bayou, it boasts a phenomenal cast that begins with Forest Whitaker (nearly ubiquitous in 2013) and ends with Angela Bassett, and it calls on the works of the great Langston Hughes to serve as its foundation. But none of that winds up mattering much, because ultimately Black Nativity winds up doing little more than just existing; it’s there, but it’s not especially good.

There’s nothing worse than reviewing a mediocre film made up of a trio of elements I actually like. In that respect, Black Nativity is a compressed version of my personal hell; it’s helmed by Kasi Lemmons, the gifted director behind such treasures as Talk to Me and Eve’s Bayou, it boasts a phenomenal cast that begins with Forest Whitaker (nearly ubiquitous in 2013) and ends with Angela Bassett, and it calls on the works of the great Langston Hughes to serve as its foundation. But none of that winds up mattering much, because ultimately Black Nativity winds up doing little more than just existing; it’s there, but it’s not especially good.

If you’re a glass half-full type, that suggests the film isn’t especially bad, either, and that’s more or less true. As a stirring, sentimental holiday picture, Black Nativity tugs heartstrings and jerks tears with saccharine majesty; as an attempted update on Hughes’ stage play of the same name, itself a reinterpretation of the nativity story told through gospel music by traditionally all-black casts, it’s a missed opportunity. In point of fact, Lemmons appears to be more interested in paying tribute to Hughes as a poet and as font of inspiration to black communities across the country, a worthy endeavor and an honor he most certainly deserves for his social activism and his contributions to the Harlem Renaissance.

If you’re a glass half-full type, that suggests the film isn’t especially bad, either, and that’s more or less true. As a stirring, sentimental holiday picture, Black Nativity tugs heartstrings and jerks tears with saccharine majesty; as an attempted update on Hughes’ stage play of the same name, itself a reinterpretation of the nativity story told through gospel music by traditionally all-black casts, it’s a missed opportunity. In point of fact, Lemmons appears to be more interested in paying tribute to Hughes as a poet and as font of inspiration to black communities across the country, a worthy endeavor and an honor he most certainly deserves for his social activism and his contributions to the Harlem Renaissance.

The problem is that in telling the story of Langston Cobbs (Jacob Latimore), Black Nativity chooses to explore both of these pursuits. There’s a distinct sense that Lemmons’ film could have sustained one or the other with ease, but intertwining them has a muddling effect that hamstrings her tightly condensed plot. It’s a kind of stilted mess, then, one that still manages to hit us in all the right places when it matters but which ultimately falls far short of establishing a cogent identity as a narrative. On one hand, there’s Lemmons riffing on the true meaning of Christmas via Red Hook Summer; on the other, a vision of Black Nativity filtered through a contemporary lens. Unfortunately, there’s only room enough for one of the two, and neither is given enough elbow room in the movie’s sub-ninety minute running time.

We start with the aforementioned young man, naturally named for Hughes himself, as he’s shipped off to New York by his mother, Naima (Jennifer Hudson), to live with her folks – Reverend Cornell Cobbs (Whitaker) and Angela Cobbs (Bassett). Grandpa and grandma (titles that they admit never comfortably fit them) have been incommunicado with their daughter for ages; the “why” is a big family secret, and one that tumbles into the open in Black Nativity‘s last act after being teased for its preceding two. Cornell is upright and uptight while Angela gets to be a bit looser, though Bassett – always fabulous no matter what mode she’s in – articulates so much thought just by pursing her lips that we get the measure of her character within minutes of meeting her.

Langston (heretofore a reference to the protagonist of the picture and not to Hughes himself), understandably, maintains reserves of deep-rooted youthful anger over his circumstances. He feels he’s to blame for the struggles Naima endures as she faces eviction and as she reluctantly involves her parents in her life after years of silence; he lacks an identifiable father figure to look up to, and only has unflattering mentions of the man who sired him to go by; he’s even racially profiled in one of the film’s greatest flourishes, suggesting that we live in a world where black youths can never break white America’s negative, media-fueled impressions of them. No wonder the kid is so pissed off.

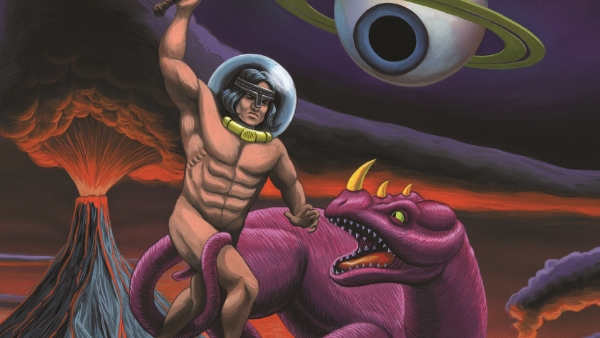

And so the mission of Black Nativity becomes one of redemption and spiritual nourishing. Lemmons hits all of the expected notes that come prepackaged with this sort of picture; call it corny and hammy, because it is, but she’s more than up to the task of making all of the expected “stuff” of its archetype work. Put simply, Black Nativity is every bit the holiday movie it should be; there’s singing, there’s dancing, everyone learns a valuable lesson in the end, and rap and R&B luminaries like Nas and Mary J. Blige show up to portray prophets and angels. Langston, partaking in the age-old tradition of nodding off in church, even experiences a vision in which he witnesses Jesus’ birth. No stone gets unturned here, though your sappy mileage may vary depending on how stony a heart beats beneath your breast.

The cast has fun, at least – they’re engaged with the material, Whitaker, Bassett, and Hudson most of all. Latimore’s a mostly untested talent, unless you consider Tyler Perry films and post-Transsiberian Brand Anderson efforts to be reasonable proving grounds (note: they aren’t), and he gives the lesser performance of the film’s primary actor core. All the same, he avails himself fine, and if he’s a bit stiff it’s hard to notice given that he’s almost always in-frame with a more veteran actor. Everyone, from a street-hustling Tyrese Gibson to the decidedly petite Bassett, towers over him through sheer force of presence; they all know how to get into their roles with better ease, and they’re more aware of the quality of the movie they’re starring in.

G-S-T Ruling:

Yet the film proves frustrating for all the glimpses we catch of what could have been. A wholesale adaptation of Hughes’ show, colored with all the requisite flourishes of modernity, could have been breathtaking; a straight-up Christmas tale infused with Hughes’ soul could have hit the most dizzying heights unabashed holiday schmaltz is capable of reaching. In truth, Black Nativity plays closely to the latter, but then there’s a question of why Lemmons felt bothered to bring Hughes into the picture at all except as a reference point – hinting at Hughes’ stage work feels like nothing more than a huge tease, the frequency with which his spirit is invoked a distraction. If the goal is to memorialize Hughes, memorialize him. Don’t simply use him as window dressing.