Blackfish director Gabriela Cowperthwaite throws a lot of information at us in less than an hour and a half, and it’s all crucial to making sense of the narrative she follows in her searing, heartbreaking, somber film. The good news is that she’s an ace filmmaker, and she knows how to convey everything that we need to know effectively, efficiently, and with clarity, but that knowledge must be served with a simple caveat: you can’t unlearn what Blackfish teaches, and that’s both a blessing and a curse. Cowperthwaite’s picture documents inhuman abuses inflicted upon non-human creatures in stunning enough detail to turn even the most dedicated SeaWorld fanatic into an outraged protester.

Blackfish director Gabriela Cowperthwaite throws a lot of information at us in less than an hour and a half, and it’s all crucial to making sense of the narrative she follows in her searing, heartbreaking, somber film. The good news is that she’s an ace filmmaker, and she knows how to convey everything that we need to know effectively, efficiently, and with clarity, but that knowledge must be served with a simple caveat: you can’t unlearn what Blackfish teaches, and that’s both a blessing and a curse. Cowperthwaite’s picture documents inhuman abuses inflicted upon non-human creatures in stunning enough detail to turn even the most dedicated SeaWorld fanatic into an outraged protester.

In fact, even a casual patron of oceanariums and zoos of any stripe may experience a twinge of guilt or a sense of culpability while watching Blackfish. Cowperthwaite has no one but SeaWorld in her sights, of course, but her film makes such a strong condemnation of their barbaric lack of ethics that it’s difficult not to project her grievances onto other similar establishments just a little bit. Not every menagerie has the power necessary to carry out the atrocities Blackfish documents, though, to say nothing of the deep-rooted depravity required to rip a young orca away from its family. What we witness here quite precisely adds up to nothing less than rank kidnapping and torture, though there’s always room to argue that animals and humans don’t equate.

In fact, even a casual patron of oceanariums and zoos of any stripe may experience a twinge of guilt or a sense of culpability while watching Blackfish. Cowperthwaite has no one but SeaWorld in her sights, of course, but her film makes such a strong condemnation of their barbaric lack of ethics that it’s difficult not to project her grievances onto other similar establishments just a little bit. Not every menagerie has the power necessary to carry out the atrocities Blackfish documents, though, to say nothing of the deep-rooted depravity required to rip a young orca away from its family. What we witness here quite precisely adds up to nothing less than rank kidnapping and torture, though there’s always room to argue that animals and humans don’t equate.

Yet Blackfish articulates the exact opposite idea, and with such passion and skill that the film’s perspective becomes impossible to ignore or even refute (though I’m not sure why anyone other than SeaWorld cronies would want to). Centrally, Cowperthwaite is concerned with the story of Tilikum, the infamous killer whale who has earned that unflattering nickname by taking the lives of three different people during his life in captivity; before she gets to him in the specific, though, she takes us forty years in the past to understand why. The film’s emphasis on misdeeds of the past require the greater part of our attention – herein is where the most data is offered to us at the fastest clip – but it doesn’t take a whale researcher, trainer, or neuroscientist to figure out where Tilikum went bad and for what reasons.

Blackfish makes the case, repeatedly, that orcas and people aren’t terribly unalike; they’re capable of forming emotional bonds, for one, though the bonds that they form with each other are even stronger than our own. (So maybe in that way they’re better than people.) Their bonds are so deep-set as to be beyond our ken, which makes the suffering Tilikum – and his mother – endured in his adolescence at least as horrific as if it had been inflicted on a human child. Indeed, when we hear the tale of Kalina and Katina, the first Baby Shamu and her mother, respectively, it becomes clear that a very real, very serious crime has been committed against them, and it slowly becomes more and more obvious how a beast like Tilikum can be driven to kill.

Isolation, neglect, exposure to physical harm…these are the transformative factors in Tilikum’s shift from gentle seafaring mammal to murderer. Separated from his family unit – we learn that a juvenile male orca will stay by his mother’s side until she dies – and put in a cramped tank with females from another “pod” entirely, Tilkum has never had a chance to live even a close facsimile to the life of a whale in the wild. Ultimately, Blackfish becomes a cautionary note about the effects alienation can have on a living being as much as a protest song against SeaWorld, a company that exposes the animals it callously yanks from their natural habitats to unfriendly environments so casually as to be appalling.

It goes without saying, then, that SeaWorld isn’t going to like this film. They’ve probably already begun railing against it with deceptive campaigns that fudge reality in big, ugly ways, but Cowperthwaite has done her homework very well and taken the time to consider the opposition. This is not a film saddled with an endless parade of yes-men lined up to obligingly validate its premise; though few and far between, and often used in service of solidifying her own thesis, Cowperthwaite refers to people on the other side of the debate, giving them a voice even though they may not strictly deserve one. It’s a sign of a shrewd filmmaker; she knows that she’s taking a stand, albeit one that’s not going to be popular in Florida, and she clearly recognizes that documentary pictures are about more than just stumping for a single viewpoint.

In the end, her bipartisan approach probably doesn’t matter; people are either going to shed tears of grief and anger over Blackfish or write it off as granola-mongering hippie claptrap. (The effort is certainly admirable.) How anyone could arrive at the latter conclusion after watching the film is a question unto itself, but SeaWorld and business like it – notably Marineland, the dingy, tin-walled prison where Tilikum got his start as a performing animal – will have their proponents regardless of how firmly Blackfish condemns them. In some respects, they even have the right idea. There are good reasons for oceanariums to exist; they’re educational, and they can be used to preserve endangered species, both noble goals that should be encouraged.

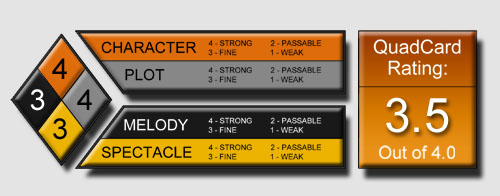

G-S-T Ruling:

But not at the cost of compassion. Early on in the film’s running time, we meet a former whaler who tells the camera straight-on and shame-faced about his experiences hunting and capturing orcas in exchange for fistfuls of cash; he exudes regret and chokes on his own words as he struggles through recollections of the wrongs he helped perpetrate. Blackfish will imbed any number of lasting images in your brain, but it’s the face of the transgressor turned remorseful old man that may linger with you longest. Whatever justifications can be made for the cruelties the film chronicles, there’s no getting around the fact that they’re simply immoral.