Following Cloud Atlas, viewers will invariably find themselves armed with a variety of useful adjectives to describe the film in a single word: grand, towering, epic, inspiring, heartbreaking, heartwarming, hodgepodge. But in adapting David Mitchell’s 2004 novel of the same name, siblings Andy and Lana Wachowski and Tom Tykwer have created a singular, unique work that majestically shrugs off attempts at quick, careless classification. Cloud Atlas is a cinematic medley of narratives connected together through time and space, driven by a sense of enterprise and purpose, and defined by its advocacy of basic, simple morality and human compassion; fitting the film into traditional categories would not be unlike forcing a square peg into a round hole.

Following Cloud Atlas, viewers will invariably find themselves armed with a variety of useful adjectives to describe the film in a single word: grand, towering, epic, inspiring, heartbreaking, heartwarming, hodgepodge. But in adapting David Mitchell’s 2004 novel of the same name, siblings Andy and Lana Wachowski and Tom Tykwer have created a singular, unique work that majestically shrugs off attempts at quick, careless classification. Cloud Atlas is a cinematic medley of narratives connected together through time and space, driven by a sense of enterprise and purpose, and defined by its advocacy of basic, simple morality and human compassion; fitting the film into traditional categories would not be unlike forcing a square peg into a round hole.

Those exact qualities, in turn, render Cloud Atlas an enormously difficult film to succinctly and easily write about in a  review format. It’s a film that on a single screening encourages rambling more than concise, focused analysis. It’s also a reminder of how good the Wachowskis can be at the height of their powers, though that does a disservice to Tykwer’s contributions as their partner in artful blockbusting crime. In fact, if I can offer any statement that communicates the essence Cloud Atlas precisely, it’s that the film happens to be the big, ambitious, idea-driven blockbuster the year has been missing. Forget the spectacle-oriented pictures of the summer, some of which do admittedly mine astounding value from their whiz-bang proclivities; Cloud Atlas operates on such sincere, emotional levels that all instances of eye candy end up reading as incidentally necessary. They exist to support theme, rather than the other way around.

review format. It’s a film that on a single screening encourages rambling more than concise, focused analysis. It’s also a reminder of how good the Wachowskis can be at the height of their powers, though that does a disservice to Tykwer’s contributions as their partner in artful blockbusting crime. In fact, if I can offer any statement that communicates the essence Cloud Atlas precisely, it’s that the film happens to be the big, ambitious, idea-driven blockbuster the year has been missing. Forget the spectacle-oriented pictures of the summer, some of which do admittedly mine astounding value from their whiz-bang proclivities; Cloud Atlas operates on such sincere, emotional levels that all instances of eye candy end up reading as incidentally necessary. They exist to support theme, rather than the other way around.

But the question of what, exactly Cloud Atlas actually is still remains. It is not a film into which futuristic gun fights figure heavily, but one in which they inevitably must occur. It’s not a chronicle of corporate espionage and intrigue, yet just such a story serves as one of its many through-lines. And it’s not a yarn about a post-apocalyptic world that resembles a future we may be heading toward, although that particular thread serves as as a bookend to the entire presentation. The most straightforward way of conveying the “stuff” of Cloud Atlas to others is to paint it as a non-linear sequence of vignettes which all explore the same concepts and motifs, but even that’s a shortchange.

Because ultimately, Cloud Atlas‘ strength doesn’t lie in its verve and daring so much as its nuance in craftsmanship. Linking together six disparate narratives over the course of a near-three-hour running time, and weaving them together with perfect cohesion are two different feats; the Wachowskis and Tykwer effortlessly succeed in the latter, far trickier endeavor, and that’s where Cloud Atlas finds its worth. For its scope, scale, and boldness, the film’s true spirit houses itself comfortably in the thematic realms that lie between and beneath every second of lush visual extravagance.

The more amazing accomplishment, then, may be that those subtler, quieter properties nevertheless assert themselves firmly in the plot even when the film ascends the highest peaks of sensory indulgence. Cloud Atlas peddles such elementary messages as “love and friendship conquer all”, “treat others the way you want to be treated”, and “be kind to people”, common sense axioms for living life that are so obviously fundamental that the opulent, enormous packaging they’re wrapped up in threatens to drown them out entirely. Yet that doesn’t happen; Cloud Atlas maintains its ideals at its forefront, and delivers them to its audience in big, powerful, affecting ways across its sextet of interrelated stories.

From the Chatham Islands in the 1850s, to 1930s Belgium, to 1970s San Francisco, to a rough approximation of the present set in England, to a dystopic near future we experience in “Neo-Seoul”, to the primitive world formed by an unnamed global disaster in a much more distant future, Cloud Atlas‘ reach is long. That’s the film’s challenge to its directing team, though: finding anchoring characteristics that resonate and afford the film an affirming sense of continuity. The Wachowskis and Tykwer answer the call with deft skill, tying together each of the innumerable threads that comprise its complex skein with an exacting cohesion. Some of the tools they employ to that end are physical, a diary here or a journal there that’s birthed in one era and harmlessly crops up in another; others are invisible, recurring motifs and scenarios that ripple across time and space– battles against injustice and corruption, portrayals of the weak triumphing over the strong.

The cast, of course, may be the strongest, or at least most notable, binding force Cloud Atlas possesses. Much has been made in the film’s marketing campaign about the presence of Hollywood luminaries like Tom Hanks and Halle Barry, but no matter how many recognizable names Cloud Atlas can claim to its credit, it’s actually a different breed of ensemble, one whose interpretation of “performance” gives the contributions of every actor an essential vitality. They shoulder anywhere between three and six roles apiece, appearing in each of the film’s timelines with either bluntly exposed obviousness (Hugo Weaving as a Nurse Ratched type) or total invisibility (none of which I’ll shed light on, because the surprise of realization is nothing short of a delight); when the disguises work, they’re seamless, and when they don’t they’re jarring, but that’s absolutely germane to the point Cloud Atlas makes.

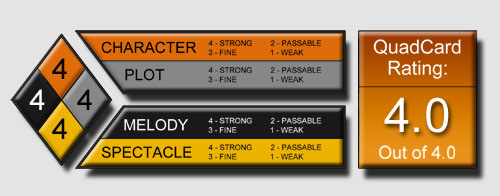

G-S-T RULING:

That point, of course, is made as loudly and brilliantly as possible, with reserves of breathtaking flare and style to assail your attention. We’re all connected, or so the film argues, but the method of debate used to make that point can only be described as harmoniously aggressive. But that’s the joy of Cloud Atlas; the Wachowskis and Tykwer go big, bigger than that, bigger still, and with no fear for the repercussions of their magniloquence. It’s impossible not to respect the fact that they’re working without a safety net no matter how one reacts to the film’s eccentricities and quirks, but Cloud Atlas is so earnestly intentioned and uncompromisingly visionary that it seems equally impossible that one could walk away from it and deem it a failure.

8 Comments

Jessica Tomberlin

awesome review, Andrew. Super excited for this one!

Andrew Crump

Thanks Jessica! I’m excited for you to see it– you’ll have to let me know what you think once you do.

Dan Fogarty

“Cloud Atlas is so earnestly intentioned and uncompromisingly visionary that it seems equally impossible that one could walk away from it and deem it a failure.”

Absolutely true. I wasn’t anywhere near as big a fan of it as you are, but I couldn’t dream of failing it, mainly for that exact reason. It’s super hard not to respect what this movie is trying to do.

I dont think it all came together. We would need a flow chart and three hours in order to discuss how story 1 led to story 2 which led to story 3, etc. But I think the connections between them all are too slight at times. Which undermines the “Causality” that they’re so intent on trying to impart. I mean, at the end of the day, this story is an epic illustration of the butterfly effect, no? Person X smiles, and 300 years later a revolution changes the world?

It just didnt all come together, even though I saw how it was supposed to. And individually I wasn’t that taken in by any of the stories, even though, collectively I did have to respect what they were trying.

It’s gonna make its fans, and its haters too. But Im with you. At the very least you have to respect the hell out of this film for trying what it tried.

Andrew Crump

I’m actually not sure about the “butterfly effect” thing. I know that the synopsis reads like a basic summary of that exact phenomenon, but the film doesn’t really do anything to support the notion that the actions that, say, Adam Ewing takes in the 1840s directly lead to the revolution in Neo-Seoul. (Not that that’s a notion you’re actually projecting, but allow me to play devil’s advocate.) I think the real thrust of film is that these situations recur and replay themselves all over the span of time, and it invites us to examine the ways in which, say, the segments that comprise the “Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing” thread reflect the plot points of the “An Orison of Sonmi-451” tale.

Surprised you weren’t taken in by the stories individually– I actually think most of them would make excellent standalone films. (Particularly “The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish” and “Sloosha’s Crossin’ an’ Ev’rythin’ After” bits. Though “Letters From Zedelghem” comes close, too.)

But I’m glad you feel the same way about the film’s respectability. It’s just too big and too eccentric and too different to be discarded.

Thanks for stopping by, Fogs!

Dan Fogarty

Its a pleasure as always bro. This was one of those films where I needed to see what you had to say. LOL. So kudos to the film in that regard, as well.

I would argue that it should either be a Events recur until someone breaks them or that one thing leads to the next leads to the next. Otherwise, whats the point?

And unfortunately, I dont see either. I think I see the “Dominoes” effect better than the skipping record. But I dont see either clearly enough to say that it all ties together on a large scale, and without that, I have to call it a huge flaw. A major weakness.

All of the tales were alright, I definitely liked the futuristic waitress clone tale. But I thought the gibberish in “Sloosha’s Crossin’ an’ Ev’rythin’ After” was a terrible distraction, to be honest. 🙁

Andrew Crump

Well, is it a matter of what it should or shouldn’t be or what it is? The film goes to great lengths to tie every story together by using recurring elements from cast members to objects (the diary, the letters, the sextet, etc). That’s the entire point and I think the only point the movie needs to be making; we’re all connected through time, space, and experience. The elderly man trying to break out of a nursing home is fighting the same battle of weak against strong as the Pidgin-speaking future dwellers in Zachry’s tale, for example– they’re echoes of each other. And I think the point in all of that is to show that humans do repeat the same behaviors and make the same mistakes, which is either harrowing and distressing or inspiring and encouraging.

I can see the Pidgin being a distracting element. I stopped trying to translate it precisely and just started worrying about picking up on context and greater meaning, but I can see how that would be kind of off-putting.

And I would LOVE to see a whole film set in Neo-Seoul. I don’t know, these worlds were so well-developed for the most part that I just want to see more of them. Though I found it somewhat surprising, honestly, that the Wachowskis felt as at home in the Chatham Islands as they do in Future Land with winged bird gunships and cloning factories.

Andrew Crump

Well, is it a matter of what it should or shouldn’t be or what it is? The film goes to great lengths to tie every story together by using recurring elements from cast members to objects (the diary, the letters, the sextet, etc). That’s the entire point and I think the only point the movie needs to be making; we’re all connected through time, space, and experience. The elderly man trying to break out of a nursing home is fighting the same battle of weak against strong as the Pidgin-speaking future dwellers in Zachry’s tale, for example– they’re echoes of each other. And I think the point in all of that is to show that humans do repeat the same behaviors and make the same mistakes, which is either harrowing and distressing or inspiring and encouraging.

I can see the Pidgin being a distracting element. I stopped trying to translate it precisely and just started worrying about picking up on context and greater meaning, but I can see how that would be kind of off-putting.

And I would LOVE to see a whole film set in Neo-Seoul. I don’t know, these worlds were so well-developed for the most part that I just want to see more of them. Though I found it somewhat surprising, honestly, that the Wachowskis felt as at home in the Chatham Islands as they do in Future Land with winged bird gunships and cloning factories.

Assorted Anomalies

Though it muses over freedom, life,

purpose of all humanity, karma and the cyclic nature of our own

existence, Cloud Atlas at its core is a beautiful love story spanning

over a period of 500 years. Some of the themes which were only hinted

in the book are made completely explicit in the movie. Especially in the

Letters to Zedelghem story Robert Frobisher is made a complete bisexual

as we see him waking up with Sixsmith at the beginning of the movie and

later falling in love with Joacsta Ayers. Similarly Hae-Joo dies while

protecting Sonmi instead of betraying her, as described in the book.

Meronym and Zachry live together happily ever after in the end. The

Luisa Rey story also ends differently on positive note. True to the

book, Adam Ewing becomes an abolitionist in a similar chain of events

and Timothy Cavendish ends up in an old age home providing some laugh

out loud moments.

Acting wise the movie is brilliant. Each

of the principal actors play five to six characters on screen and all of

them do justice to their respective role. Special mention must be made

of Tom Hanks who has simply given some of his finest performances of his career and Doona Bae, the acclaimed Asian actor who shows her polished acting skills as Sonmi. Halle Berry

and others stand out as the supporting cast. Cloud Atlas also shows

some of the best make-up work I’ve ever seen in movies. For instance, in

the Cavendish story Hugo Weaving plays a Nurse Ratched

like character without you even doubting it. The end credits are

equally innovative where we see montage of the characters played by an

actor. The cinematography, editing (as good as Memento) and art direction are top notch. Tykwer & Co. have also composed a mesmerizingly haunting score as the Cloud Atlas Sextet which stands out.

A little longer review here

http://assortedanomalies.wordpress.com/