As a young lad, my measure of acquaintance with Diana, Princess of Wales started and stopped with the following details: she was British, beautiful, and a hair’s breadth from sainthood. Her death in 1997 meant little to me as a sheltered American boy, and only signified that the people I saw on television weren’t immune to harm or free from danger. The vulturous ethics of the paparazzi culture that was so thoroughly alien to my thirteen year old self, of course, has become much more familiar to me since, so today, at the very least, I can appreciate the cultural significance of her demise more than a decade and a half ago.

But that awareness ends up working against Oliver Hirschbiegel and his attempts at honoring Lady Di in his latest film. Diana is risible for a number of reasons, but as Hirschbiegel’s movie documents the final two years of its subject’s tragically short life, there’s a duality that comes into play: he’s tarring and feathering the parasitic, aggressively trigger-happy (“shutter release-happy” doesn’t quite roll off the tongue as smoothly) tabloid creeps whose incessant flash photography has made them guilty of killing Diana in the public eye, all while indulging himself in the same sort of frenzied, glitzy carrion feeding at the exact same time. The message appears to be that violating celebrity privacy is a crime, unless you’re trying to make “art”.

But that awareness ends up working against Oliver Hirschbiegel and his attempts at honoring Lady Di in his latest film. Diana is risible for a number of reasons, but as Hirschbiegel’s movie documents the final two years of its subject’s tragically short life, there’s a duality that comes into play: he’s tarring and feathering the parasitic, aggressively trigger-happy (“shutter release-happy” doesn’t quite roll off the tongue as smoothly) tabloid creeps whose incessant flash photography has made them guilty of killing Diana in the public eye, all while indulging himself in the same sort of frenzied, glitzy carrion feeding at the exact same time. The message appears to be that violating celebrity privacy is a crime, unless you’re trying to make “art”.

Of course, Hirschbiegel deserves the benefit of the doubt – perhaps none of this is his intention whatsoever. If so, then he’s still culpable for making a very bad movie, one that trades on any sense of responsibility to truth and realism to paint an embarrassingly schmaltzy portrait of a very real human being. That’s a very bitter irony; no matter what his ancillary aims may have been, Hirschbiegel undoubtedly wanted to humanize Diana, to peel back the layers of her persona so as to show the vulnerable, fractured person beneath. Funny that anyone would undertake such an endeavor by making what essentially amounts to a coltish, ham-handed romantic drama.

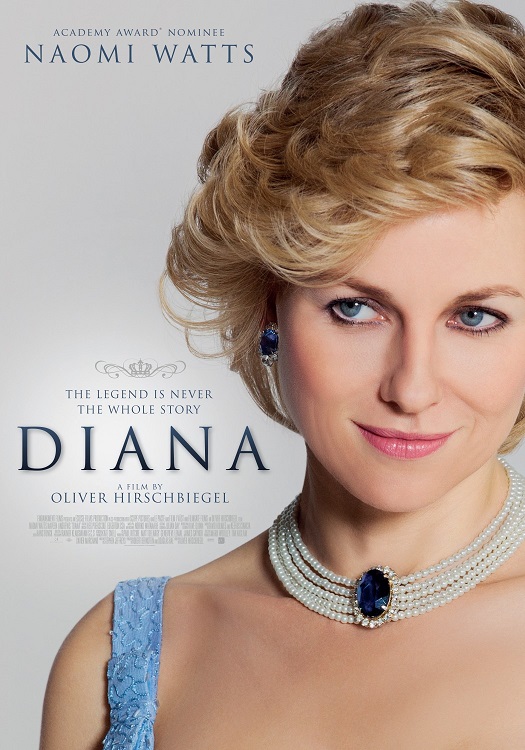

Everything about Diana reads disingenuously. Its liveliest elements come packaged within the slender, luminous frame of Naomi Watts, stepping into the Princess’s shoes, and the smoldering manliness of Naveen Andrews, here playing Hasnat Khan, the Pakistani lung surgeon thought by many to be the love of Diana’s life. Watching them act is painful, not because they’re bad – occasionally blustering, but never appalling – but because they’re saddled with material that’s tragically beneath them; they deserve all the credit in the world for making the best of a saccharine situation. As envisioned by Hirschbiegel, Diana adds up to little more than a tittering, love-struck school girl, while Hasnat’s just a hunky medical genius with an affinity for jazz and an inclination toward minor hypocrisy.

To an extent, that characterization is unfair; Hirschbiegel paints Diana with more layered brushstrokes than that, but the qualities that resonate most strongly are the ones he lifts straight out of rom-com territory. This is Diana of Wales! She deserves a far better artistic commemoration than this! At the very least, Diana feels obligated enough to depict the charity she did as the princess of our hearts – notably the strives she made and the risks she took to eliminate the manufacturing and deploying of anti-personnel landmines in Angola – but these bits feel like gimmes. They exist to remind us that Diana accomplished great things in her life, but they’re never made into core issues of importance.

Primarily this is a scandal picture. It’s a film that’s all too happy to mire itself in the gossip-mongering that hounded Diana for the rest of her days after her split with Prince Charles; Hirschbiegel only contextualizes all of that boring stuff about royal responsibility and human compassion – you know, all of those good things that made Diana matter to her people – within the framework of her love life. I imagine that there’s actually a good movie to be made about the inherent tension between being a public figure, known to everyone across the globe, and being a person who just wants to find intimate companionship. This isn’t it. Someone might have the gall to argue that using this conflict as a focal point makes Diana more real, but all that results from Hirschbiegel’s pursuit of “the story” is a hundred and twenty minutes of irresponsible filmmaking.

Diana crashes and burns in such spectacular fashion that imagining how anyone involved didn’t foresee its tragically inevitable failure is simply impossible. As a made-for-TV movie, Hirschbiegel’s efforts might have been better appreciated; he doesn’t do much more than scratch at the surface, flitting by details that could have made for a more arresting film. This is a woman driven to self-mutilation despite the comfort and luxury that shaped her existence (or perhaps because of it), something that Diana touches on but briefly before sweeping it under the rug. There’s such a wealth of material to be spun out of the events of her life that the decision to lean on the most rote, acceptably mainstream elements feels like a hackish cheat.

G-S-T Ruling:

Maybe the big problem here is that Hirschbiegel walks right into the number one pitfall most biopics contend with by choice: he takes on far too much, going broad instead of going narrow. His film always comes back to when Hasnat met Di, but one wonders if Diana would have been significantly improved if it had just invested itself in its two central characters and shoved everything else off to the side. (We don’t need to speculate on whether doing the reverse would have been a smart move – of course it would have.) We’re left wondering whether Hirschbiegel’s work represents a greater slight against Diana or the talented actress portraying her, though this is such a disgraceful movie that it hardly matters in the end; Diana doesn’t seem to think much of them either way.

2 Comments

Colin Biggs

This reeked of the tabloid frenzy that the film proposes to be against. I’m sorry you had to sit through it, I couldn’t even muster the energy for a review.

Andrew Crump

Didn’t take me much time to write this up – my feelings on it were that clear and that strong. Boy, I did not like it. I feel so sorry for Andrews and Watts.