Joshua Michael Stern’s Jobs has one question to answer, and one question only: can the towering genius of the late Steve Jobs be adequately embodied by Michael Kelso on the big screen? Every critic reviewing the film will inevitably struggle to utter, “yes”, if only because no one wants to risk their credibility by going to bat for an Ashton Kutcher performance. But, miracle of miracles, he’s actually pretty good, good enough at least to warrant real praise instead of yawning skepticism or begrudging acceptance, but not necessarily good enough to raise Jobs above the sub-standard, thoroughly muddled biopic Stern crafts around his lead’s portrayal of Apple’s driven, visionary, and utterly ruthless co-founder.

In truth, showcasing Jobs’ more dispassionate qualities may well be the best decision that the film makes outside of casting Kutcher. (That’s a sentence nobody ever expects to write.) We’re still only two years out from his death, after all, and so there’s greater temptation to lionize him instead of illustrate his better and worse qualities in two hours of storytelling. Stern wisely chooses to offer us moments of Jobs at his most heartless, from the 1970s – where our story starts, with a young Jobs who’s literally too cool for school – all the way up to the 90s, when he returned to the company he helped create after being ousted by his shareholders in 1985.

In truth, showcasing Jobs’ more dispassionate qualities may well be the best decision that the film makes outside of casting Kutcher. (That’s a sentence nobody ever expects to write.) We’re still only two years out from his death, after all, and so there’s greater temptation to lionize him instead of illustrate his better and worse qualities in two hours of storytelling. Stern wisely chooses to offer us moments of Jobs at his most heartless, from the 1970s – where our story starts, with a young Jobs who’s literally too cool for school – all the way up to the 90s, when he returned to the company he helped create after being ousted by his shareholders in 1985.

Which brings us full circle to Jobs‘ most significant problem: it’s too damn ambitious. This is a film that bears a passing family resemblance to The Social Network and tries very, very hard to get its audience to notice it; the problem is that Stern and screenwriter Matthew Whiteley bit off more than they could chew at the script level, and nobody could decide on what the narrative needed to cover and what it needed to overlook. The Social Network can get away with dramatizing the entire history of Facebook thanks to its recency and minute time span (and even then it’s still akin to Cliff Notes), but Jobs foolishly tries to distill twenty plus years of technological progress and development – told as a board room thriller – into one hundred and twenty minutes of cinema.

It’s too much. Too, too much. Then again, maybe a Fincher and a Sorkin could have done it; Stern doesn’t present himself as a particularly adept filmmaker, wasting an absurd amount of time on inconsequential detail and nonsensical faux-artistic flourishes. Do we need to spend five minutes experiencing one of Jobs’ collegiate acid trips as the camera cuts between ill-contextualized moments of his travels to India and whirling shots of Kutcher frolicking through a field of grass? Probably not. Arguably, these are the beats that give the man he’s playing pathos, but the end result is nothing more than a lot of silliness brought to bear by terrible filmmaking. (There’s a scene right out of Batman Begins where Jobs, in a fit of pique, makes the transformation from hippie idealist to uptight inventor by tucking in his shirt while brooding into a mirror.)

Frustratingly, we never end up really learning who Steve Jobs is or what motivates him. To his great credit, Kutcher strives to convey the inner workings of the man and give us a glimpse into his mind. Your mileage may vary over whether his efforts are well-spent or not; every smart choice he makes is ultimately in service of an appallingly underwritten production, which is a nice way of saying that he’s wasted on the material. Don’t go into Jobs expecting Oscar-caliber work from the once and future Punk’d purveyor – he’s legitimately good, adopting all kinds of nifty physical ticks and flourishes (like his slouching stance and awkward gait) as part of the transformation, but this isn’t his Lincoln.

Thankfully, it’s not his Hitchcock, either. (It could be his Infamous, though, at least if Aaron Sorkin’s own impending Steve Jobs biopic has anything to say about it.) Kutcher’s craft doesn’t go full-on ham-handed, and he’s surrounded by a very able supporting cast. The real star here might actually be Josh Gad, the man responsible for originating the role of Elder Cunningham in The Book of Mormon and a network TV fixture. As good as Kutcher is, Gad is ever so slightly better as Steve Wozniak, the unsung hero of Apple’s rise to prominence; when he departs from the narrative, we’re poorer for it. That still leaves Kutcher with a plethora of other talented people to play off of – Dermot Mulroney, Matthew Modine, J.K. Simmons, Nelson Franklin, Kevin Dunn – but Jobs is never more watchable than when it holds him and Gad in the frame together.

And that’s it. That’s what viewers get. Good performances in an aimless, scattered, dishonest movie. Everything that Stern gets right comes in tandem with a lot of whitewashing and outright fabrication about what Steve Jobs accomplished in his life as a businessman and innovator; contrary to what Jobs tells us, he invented neither the MP3 player, nor the mouse, and he liberally borrowed ideas from Xerox to create the graphical interface that Bill Gates ‘steals’ from him in the film. (Interpret the words “borrow” and “steal” only in the loosest sense possible.) The film skirts reality. Admittedly, this is for good narrative reasons, but that only emphasizes how loudly Jobs cries out for a more surgical editing session.

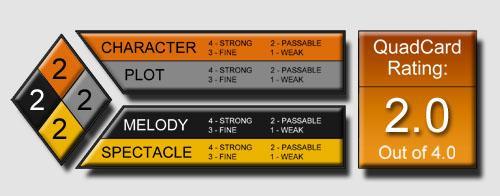

G-S-T Ruling:

More importantly, Jobs doesn’t bother to say anything about what any of Jobs’ contributions really mean, and as a consequence it loses the value of a central message. Is this a cautionary tale about doing whatever it takes to succeed? Is it a portrait of how callousness and next-level talent often come packaged together? Whether he’s denying parentage of his firstborn daughter or quietly cutting Apple’s other co-founder out of stock options, Steve never fails to undermine his brilliance with his cold inhumanity. Maybe, then, there’s at least something to the latter query, but it’s still not enough to give Jobs anything to stand on other than the shoulders of its subject.

2 Comments

Colin Biggs

With such a divisive figure and a lot of ground to cover, I’ll be waiting for the Sorkin penned film to hit theatres.

Good for Kutcher though, I’m sure he’ll need more palette cleansers after a few more years of 2 1/2 Men.

Andrew Crump

Definitely. If he can turn out work like this, he should really consider getting away from bad TV and starring in good movies.

The Sorkin version has me in the thralls of anticipation, though.