Sheldon Candis’ greatest coup in directing LUV, his debut feature, could well be securing rapper-turned-all-around-entertainer Common as his leading man. Common only started making moves in the acting world in the early 2000s before landing roles in Smokin’ Aces and American Gangster in 2007, but he’s been writing rhymes about manhood and the value of family since 1992; combining that background with his natural, easy charisma, he feels like a natural fit for a story about a young boy learning life lessons from his uncle over the course of a single day in inner city Baltimore. When Common speaks, he speaks with authority. Were we in Michael Rainey Jr.’s place, we would come to idolize him, too.

Sheldon Candis’ greatest coup in directing LUV, his debut feature, could well be securing rapper-turned-all-around-entertainer Common as his leading man. Common only started making moves in the acting world in the early 2000s before landing roles in Smokin’ Aces and American Gangster in 2007, but he’s been writing rhymes about manhood and the value of family since 1992; combining that background with his natural, easy charisma, he feels like a natural fit for a story about a young boy learning life lessons from his uncle over the course of a single day in inner city Baltimore. When Common speaks, he speaks with authority. Were we in Michael Rainey Jr.’s place, we would come to idolize him, too.

Unfortunately Candis doesn’t generate the same kind of gravitational pull with his own efforts here. LUV feels like an earnest effort to tell a genuine story, but Candis has his mind firmly trapped in the work of Antoine Fuqua and David Simon; he’s basically remade Training Day through the lens of The Wire, but without earning any of the violent sensationalism of the former or fostering the high verisimilitude of the latter (there’s more to Baltimore than the Ravens and crabs). He’s also established that he has a knack for working with his actors, but no matter how many strong performances (whether they’re simple cameos or more pivotal turns) LUV can claim credit for, they’re not enough to obscure the fact that Candis has no idea what kind of movie he wants to make.

Unfortunately Candis doesn’t generate the same kind of gravitational pull with his own efforts here. LUV feels like an earnest effort to tell a genuine story, but Candis has his mind firmly trapped in the work of Antoine Fuqua and David Simon; he’s basically remade Training Day through the lens of The Wire, but without earning any of the violent sensationalism of the former or fostering the high verisimilitude of the latter (there’s more to Baltimore than the Ravens and crabs). He’s also established that he has a knack for working with his actors, but no matter how many strong performances (whether they’re simple cameos or more pivotal turns) LUV can claim credit for, they’re not enough to obscure the fact that Candis has no idea what kind of movie he wants to make.

LUV begins promisingly enough: with Woody (Rainey Jr.) awakening from a dream where he’s in the woods with his mother before getting dressed while practicing his tough guy stance in the mirror. It’s economical filmmaking that gives way to a stiffer bit of set-up before Woody winds up skipping out on school to help his uncle, Vincent (Common), “take care of some business” around town. Vincent’s has an honest objective – he wants to open a restaurant on the waterfront– but you’ve probably heard that Satan’s public works guys paved his road with the good intentions of decent people a long, long time ago.

So a spanner gets thrown in Vincent’s works and he stoops to less pure methods of seeing his dream become a reality. Even when Vincent consciously begins exposing the impressionable Woody, torn between his love for comic books and the macho bravado his uncle embraces, to the life that put him in jail for almost a decade, LUV at least has something interesting to say about ends, means, and morality. There’s a question here as to whether Vincent’s actually doing right by his nephew or if he’s selfishly trying to achieve his own goals, consequences be damned; it isn’t earth-shattering stuff, but Candis clearly has an eye for relationships, and so the film works as long as he maintains the focal point of Vincent’s and Woody’s bond.

But then LUV makes a sharp left turn and becomes a bullet-addled, painfully standard tale of police procedural drama, criminal politics, and familial deception. The tone changes jarringly, and we start watching a very different movie from the one we were previously watching. There are similarities, of course– both movies are about Vincent and Woody, for example, but one of them explores the boy’s coming of age and his hero worship while the other positions both of them in matters of life and death as Vincent’s shady past catches up to them. Maybe if LUV didn’t treat Vincent’s crimes as surprising reveals, the film’s second half wouldn’t feel so disjointed; maybe if the ways in which the plot goes from bad to worse weren’t transplanted from another movie entirely, the conflict here wouldn’t feel so inorganic.

It’s a Frankenstein’s monster scenario. Candis stitches LUV together using too many disparate parts, and while the results occasionally work– either through emotional resonance or aesthetics– they’re far too uneven. By the time the film arrives at it climactic scene, a confrontation between Common, Dennis Haysbert, and Danny Glover, there’s an unshakable sense that something’s missing in the preceding hour of footage. Could LUV be the victim of over-editing? Part of me wonders if there’s material on the cutting room floor that better informs the pain and rage Common and Haysbert convey to one another. Another part of me suspects that Candis just didn’t know how to find harmony within the various genres and traditions he leans upon here.

If there’s a single area in which Candis excels, it’s directing his cast. The performances here are uniformly good, though Glover doesn’t have anything substantial to work with so he’s reduced to spurts of small talk and gruff laughter, while Charles S. Dutton is criminally wasted. Haysbert, however, avails himself well as one of Vincent’s former partners in crime; he’s a glimpse of what Vincent could be, and Haysbert’s booming voice carries an older sort of power that matches Common’s own. They work well together when they’re on-screen, but in the end it’s Common himself who comes out ahead, further proving himself as a performer even if the rest of the movie lets him down somewhat.

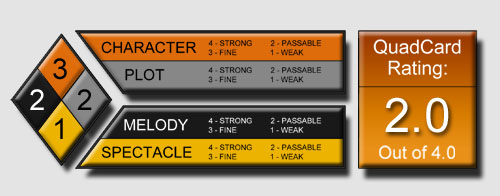

G-S-T RULING:

In the middle of it all is Rainey Jr., stuck between LUV‘s impressive cadre of actors (which also includes Michael K. Williams and Meagan Good, but they have so little screen time here they’re almost not worth mentioning). Wide-eyed and malleable, Rainey Jr. admirably blends into the crowd, which may be part of the point and is certainly no small feat standing next a cast this talented. Truthfully, LUV may be a better first outing for him than Candis, but that does a disservice to what Candis is able to pull off. His film may be lopsided and jagged, but he manages to avoid stereotypical pitfalls and cliches, and that’s worth some praise when so much American cinema embraces those exact elements.