Mexico’s longstanding drug war has made for some stellar visual media in the last few years, influencing aspects of shows like Breaking Bad and providing a blueprint for films like 2012’s Savages or, much more recently, The Counselor; sitting pretty from afar, the ultra-violence that punctuates the wheeling and dealings of this outrageously lucrative business makes for a viscerally captivating narrative, allowing us to portray the realities of cartel brutality while skirting around genuinely confronting them. It’s human tragedy made into slick entertainment, not necessarily ignorant of the legitimate suffering they’re cashing in on but almost always woefully reluctant to fully confront it.

Shaul Schwarz, however, isn’t satisfied with addressing the bloodshed through fiction, and in his debut documentary, Narco Cultura, he faces all of it head on and at street level. Coming into a release year that’s overflowing with gutsy, daring docs – start with Blackfish, end with The Act of Killing – Schwarz’s film may be the ballsiest offering on 2013’s slate. He’s fashioned a big-picture perspective on an alarming, all-too-current event, but he’s also wisely attached himself to two very different men on polar opposite ends of the seemingly endless conflict that’s been consuming Juarez – the murder capital of Mexico and one of the most dangerous cities on the planet – since 2008, blurring the lines in a way that blunts and provokes our ire at the same time.

Shaul Schwarz, however, isn’t satisfied with addressing the bloodshed through fiction, and in his debut documentary, Narco Cultura, he faces all of it head on and at street level. Coming into a release year that’s overflowing with gutsy, daring docs – start with Blackfish, end with The Act of Killing – Schwarz’s film may be the ballsiest offering on 2013’s slate. He’s fashioned a big-picture perspective on an alarming, all-too-current event, but he’s also wisely attached himself to two very different men on polar opposite ends of the seemingly endless conflict that’s been consuming Juarez – the murder capital of Mexico and one of the most dangerous cities on the planet – since 2008, blurring the lines in a way that blunts and provokes our ire at the same time.

Without showing much by way of hesitation or fear, Schwarz and his crew settle themselves in proximity of Richi Soto and Edgar Quintero. The former is a crime scene investigator and Juarez local, crestfallen at how far his hometown has fallen during gruesome rise of the Sinaloa Cartel, one of Mexico’s most prominent crime syndicates; the latter, a musician who plies his trade writing narcocorridos, songs that romanticize and glorify the ruthless barbarity that encompasses the daily existence of cartel gangs and the innocent civilians who get caught in their path and chewed up like so much gristle. It’s music that continues to gain traction in Mexico and the US even today, despite a ban preventing it from being played over Mexican airwaves.

In a film littered with images of actual victims of actual cartel savagery – some so graphic as to be stomach churning – the greatest ignominy Schwarz captures is in the disparity in how Soto and Quintero live out their days. While Soto’s life essentially occurs only between his office, Juarez’s crimson-streaked street corners (there’s a scene where a man mops a literal river of blood into a catch basin) and the iron-barred confines of his house, Quintero receives fat wads of cash from killers who commission his talents; he’s revered almost as much as the men he sings about. Kids wear T-shirts with his and his band mates’ likenesses emblazoned on them, while members of the Sinaloa Cartel upload video shout-outs on Youtube, replete with an assault rifle salute. Injustice of injustices.

Quintero might be the most contemptible human being in the piece if Schwarz were a less considerate filmmaker. His income adds up to a whole lot of blood money, and – perhaps worst of all – he and his compatriots in musical outfit BuKnas de Culiacan are a bunch of posers. None of them has ever set foot in Mexico; Narco Cultura gives them a chance to visit the Sinaloa’s home turf, an opportunity they embrace by snorting coke and touring an opulent city of tombs, where deceased narcos are interred alongside their most prized possessions (including, but not limited to, their trucks). It would be disgraceful if it wasn’t so goddamn appalling.

Admittedly, Schwarz has the decency to show where Quintero comes from; he’s a family man, and from what we see of his life at home, his aspirations are his own. His wife appears to tolerate what he does only because it pays the bills and then some, and she never comes close to embracing the narco culture like Quintero does. That tempers some of the acrimony we feel toward the man, but after a point, Narco Cultura starts to suggest that part of what gives the cartels comes from how much people like Quintero turn their exploits into product, and turn that into revenue. The comparisons made between narcocorridos and gangster rap feel like a joke; maybe both categories treat outlaws like contemporary Robin Hoods, but the former doesn’t find its roots in non-discriminant slaughter.

On some level, there is a kinship present there: Schwarz contrasts the horror of Sinaloa with the cognitive dissonance seen in dance halls, where blissfully ignorant crowds groove to the polka-influenced cadence of the narcocorridos without ever really connecting with what each ditty is actually about. People won’t hesitate to buy into image if that image projects an attractive enough lifestyle, fie upon the ugly truth lying beneath its surface. Narco Cultura shows off so much footage of the dead and their surviving relatives that we only assume that patrons of groups like BuKnas de Culiacan don’t even have the faintest clue what’s happening south of the border – they just care about the never-ending party and the indulgence that comes part and parcel with the music. Whatever helps them sleep at night.

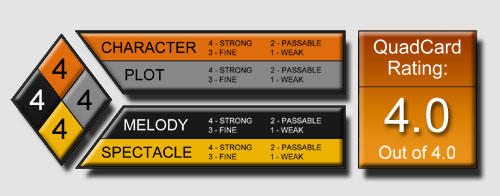

G-S-T Ruling:

The heart that silently beats beneath all of Schwarz’s efforts, though, is Soto. He’s the very definition of an unsung hero; the people he theoretically serves through his profession (only 3% of the incidents processed in his line of work actually get investigated) don’t even hold the cartels responsible for the genocide occurring around them, accusing the police of executions and gang collusion. The hell of it is that they’re not wrong, but they’re wrong about honest cops like Soto. He’s the cheese left standing alone – we learn, through a cleverly executed sequence of photographic fade-outs, that his colleagues and friends have been dropping like flies around him for years, with each assassination simply ratcheting up Juarez’s staggering homicide statistics – and there’s no light at the end of the tunnel for him or for his city.

We want to assign blame to somebody – whether it’s the “artists” behind the narcocorridos or the men pulling the triggers – and sure enough, there’s plenty to go around. But as the camera captures one last shot of Juarez’s decrepit, corrupted urban wasteland, finger-pointing feels utterly fruitless. The narcos have won.