For most of us, a day out in the cities we live in doesn’t represent a strictly dangerous prospect. From street to street, familiarity engulfs us and fosters in us a sense of mundane security; the haunts and locales we visit and patronize become so commonplace that we could never construe them as harmful to our well-being. For Anders, the principal character of Norwegian director Joachim Trier’s sophomore effort, Oslo, August 31st, a single twenty four hour span of time is fraught with the perils of temptation, populated with ghosts from his past, and resonant with the echoes of his guilt and shame. Such are the circumstances of a recovering addict. No person or place is quite the same as it once was.

For most of us, a day out in the cities we live in doesn’t represent a strictly dangerous prospect. From street to street, familiarity engulfs us and fosters in us a sense of mundane security; the haunts and locales we visit and patronize become so commonplace that we could never construe them as harmful to our well-being. For Anders, the principal character of Norwegian director Joachim Trier’s sophomore effort, Oslo, August 31st, a single twenty four hour span of time is fraught with the perils of temptation, populated with ghosts from his past, and resonant with the echoes of his guilt and shame. Such are the circumstances of a recovering addict. No person or place is quite the same as it once was.

We meet Anders as he’s temporarily released into the world from the rehab facility that has taken custodianship of him. His return to real life is intended to be brief; as part of his program, he’s allowed one day to visit the eponymous city in order to attend a job interview set up for him by his counselor. Of course, that’s easier said than done. Simply permitting Anders to set foot in Oslo is itself deceptively tantalizing, and maybe it’s not much of a surprise that the young man ends up spending more time catching up with his friends and family than he does on his appointment. If the trip down memory lane doesn’t appear to be all that dangerous at first blush, it becomes clear that every run-in with an acquaintance– his best friend, his sister’s girlfriend, his own ex-lover– serves as a testing ground for Anders’ willpower and presents a potential trigger for his addiction.

We meet Anders as he’s temporarily released into the world from the rehab facility that has taken custodianship of him. His return to real life is intended to be brief; as part of his program, he’s allowed one day to visit the eponymous city in order to attend a job interview set up for him by his counselor. Of course, that’s easier said than done. Simply permitting Anders to set foot in Oslo is itself deceptively tantalizing, and maybe it’s not much of a surprise that the young man ends up spending more time catching up with his friends and family than he does on his appointment. If the trip down memory lane doesn’t appear to be all that dangerous at first blush, it becomes clear that every run-in with an acquaintance– his best friend, his sister’s girlfriend, his own ex-lover– serves as a testing ground for Anders’ willpower and presents a potential trigger for his addiction.

Somewhat surprisingly, addiction isn’t Oslo, August 31st‘s primary focus. Trier uses it more as a foundation on which to build an examination of Anders’ crushing guilt. This isn’t Requiem For a Dream: Norway, but a smaller, more personal story, one that deals specifically with the fallout of addiction instead of the process. Anders, on the path to recovery, is hounded by demons everywhere he goes; his transgression hangs over his head like a funeral pall, influencing the way others perceive him (or, more accurately, the way he assumes other people perceive him). He wrestles constantly with existential despondency, laboring under the belief that his friends, family, and society at large won’t accept him as a former junkie.

And watching him struggle to shoulder the burden of his discontent is heartbreaking. Oslo, August 31st is characterized foremost by a sense of separation from its subject, and the distance Trier places between himself, Anders, and their audience only serves to heighten the sense of isolation Anders experiences from frame to frame. It’s a ripple effect; the farther Anders falls, the more stolid Trier’s filmmaking becomes, the further we feel removed from the proceedings. The greater result is that we come to feel helpless ourselves when faced with the enormity of Anders’ plight by virtue of how much space lies between us and him.

That’s not a slight against Trier’s talents as a director, or a remark on his failure to invest us in his film, however. If Oslo, August 31st is clinically made, it’s emotionally well-realized. Trier’s dispassionate camera exists to capture the very human, very real performances of the movie’s cast, notably that of leading man Anders Danielsen Lie (who also starred in Trier’s 2006 debut, Reprise). No tension exists between Oslo, August 31st‘s clean, detached aesthetic and the involved, veracious timbre of the acting; the sense is that Trier is making a document as much as he’s putting on a show, though it may go without saying that there’s nothing glitzy about his film at all.

Oslo, August 31st exists in the realm of stark, unforgiving realism, where redemption and damnation lie within a hair’s breadth of one another. Perhaps that’s overstating the film’s case– it’s much quieter and more restrained than that– but Anders walks a fine line as he traverses the path to freedom from his drug dependency. Every moment presents an opportunity for him to crumble over his regret, or to better himself and move forward.

But the tragedy of Oslo, August 31st is that Anders entrenches himself in the past. A remarkable non-professional actor, Lie portrays Anders as an earnest, anguished hangdog; he’s genuinely remorseful for his misdeeds and how they’ve affected the people he cares about. He almost feels too bad about his errors, an attribute built into the character and not simply born out of Lie’s efforts. Anders’ shame keeps him stuck in neutral, and practically makes him a phantom presence in every setting he wanders into. Responding to each moment of his day with either stubborn, concrete nihilism or gallows humor, it becomes apparent quickly that Anders’ feeling of hopelessness is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

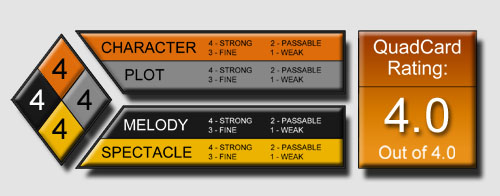

G-S-T RULING:

Yet Trier isn’t wallowing in lugubrious oblivion. Quite the opposite, in fact. Each scene is actually an invitation for compassion. Trier’s approach belies how much he cares about his protagonist, and how much he intends his audience to empathize with Anders as well. Oslo, August 31st is a bleak picture, but one of supreme beauty that bears a great deal of sympathy for the rehabilitated. It’s the film’s through-line, though Trier does not attempt to delude or mislead his audiences with the promise of a strictly pretty outcome. All the while, Anders roams the streets of Oslo (itself an integral character in the film), listens to the whispers of its inhabitants, and tunes in to the city’s memories. They’re the commonplace murmurs of daily life that we take for granted, but which Anders, whose existence differs so vastly from our own, inwardly cherishes in his austere way.