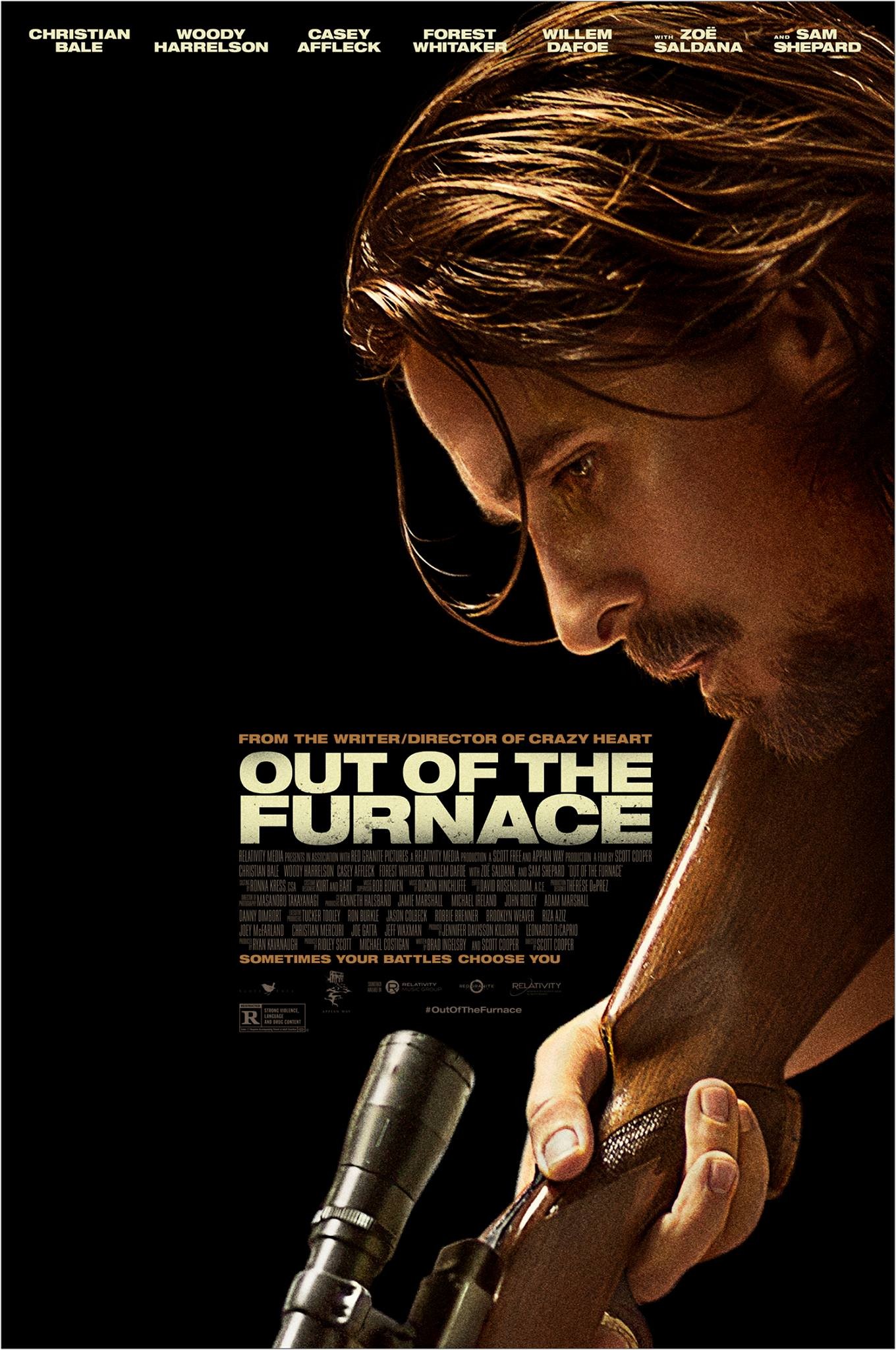

You can take the Oscar bait out of the gritty revenge thriller, but you can’t take the gritty revenge thriller out of the Oscar bait. So goes Out of the Furnace, Scott Cooper’s latest film since 2009’s deplorably hackneyed Crazy Heart; in just under two hours of running time, Cooper never makes the effort to determine whether he’s making a sweeping, important piece of arthouse cinema, or a good old fashioned genre picture. Truthfully, that’s by design – he’s very clearly bent on mashing these two pursuits together from the very start, hoping that by adding two and two he’ll come out the other side with a handsome bit of archetypal blending.

You can take the Oscar bait out of the gritty revenge thriller, but you can’t take the gritty revenge thriller out of the Oscar bait. So goes Out of the Furnace, Scott Cooper’s latest film since 2009’s deplorably hackneyed Crazy Heart; in just under two hours of running time, Cooper never makes the effort to determine whether he’s making a sweeping, important piece of arthouse cinema, or a good old fashioned genre picture. Truthfully, that’s by design – he’s very clearly bent on mashing these two pursuits together from the very start, hoping that by adding two and two he’ll come out the other side with a handsome bit of archetypal blending.

The problem, though, is that he’s a seriously klutzy storyteller, and he lacks the requisite filmmaking chops to reconcile one angle against the other. In his hands, Out of the Furnace turns out ghoulishly, a poorly stitched project that doesn’t even manage to get its disparate halves correct on their own terms; as vengeance-fueled exploitation yarn, it’s antiseptic and anticlimactic, and as a sorrowful, grimy, slice of life awards magnet, it’s unimaginative and tragically dull. There’s almost no level on which this movie succeeds, in other words, and “almost” applies as a qualifier due solely to an absolutely fantastic opening scene involving Woody Harrelson, a Ryuhei Kitamura joint, and a hot dog.

The problem, though, is that he’s a seriously klutzy storyteller, and he lacks the requisite filmmaking chops to reconcile one angle against the other. In his hands, Out of the Furnace turns out ghoulishly, a poorly stitched project that doesn’t even manage to get its disparate halves correct on their own terms; as vengeance-fueled exploitation yarn, it’s antiseptic and anticlimactic, and as a sorrowful, grimy, slice of life awards magnet, it’s unimaginative and tragically dull. There’s almost no level on which this movie succeeds, in other words, and “almost” applies as a qualifier due solely to an absolutely fantastic opening scene involving Woody Harrelson, a Ryuhei Kitamura joint, and a hot dog.

If that sounds like a great start to any movie, it is, but only a handful of the sequences that follow present a pulse at all. Harrelson isn’t even the hero of the piece – that honor goes to Christian Bale, gone full-on blue collar as Russell Baze, a Pennsylvania steel mill worker struggling to make ends meet and keep his younger brother, Army veteran Rodney (Casey Affleck), out of trouble in the state’s economically depressed Rust Belt. A drunken car accident derails Russell’s plans, though, and when he eventually gets out of the clink, he finds he’s too late to keep Rodney from making the worst decision of his life: tangling with the Wrong People in an illegal bare knuckle boxing racket.

That’s where Harrelson’s character, redneck lunatic Harlan DeGroat, comes in: he’s the Wrong Person at the head of a pack of Wrong People, the kind of guy who happily wakes up every the morning to a needle and a spoon. Cooper layers neat movie references over our first encounter with Harlan- he’s watching Midnight Meat Train at a drive-in in 2008 (because The Dark Knight would have been too obvious), while doing a pretty stellar impression of the titular character from Killer Joe using a Ballpark Frank (because Harrelson just can’t resist mimicking best buddy Matthew McConaughey). Had Out of the Furnace gone forward with Harlan as the primary character, Cooper might have had something interesting on his hands, but nothing in the rest of the film lives up to this introduction in the slightest.

In fact, practically nothing that happens in that scene actually ends up matter in the long run; the only relevant information provided is that Harlan is a hyper aggressive jerk, and anyone who gets in his way ends up flattened on the ground. Russell and Rodney, by contrast, receive much, much less characterization, most of it half-baked and cribbed straight from the headlines. America mistreats its military vets! Times are tough for trades guys and factory employees! Obama, Obama, Obama! Coooper’s trying to be sharp and relevant but there’s never a moment where any of his Wikipedia talking points cohere to make a statement. They barely even matter as far as setting tone and establishing time. If anything, these elements read as arbitrary when they should be instrumental toward giving the film cultural identity.

Of course, Out of the Furnace remains unmistakably American, but only in the most irrelevant ways possible; the stronger identifier here is an over-trumped sense of gravity, seen in the broad flourishes the cast brings to their individual performances as well as the overall aesthetic quality of the film. Out of the Furnace wants to be taken seriously, craves recognition as a work of towering value; it demands your attention, in other words, but Cooper has no gift for drama, and so the entire production plays like an awkward stage play. His basic concept of what makes a movie dramatic comes down to mumbled line readings and muted color palettes. Apparently the less you can understand dialogue and the uglier a picture looks, the more meaningful it becomes.

The burden of coherence can’t be put entirely on Cooper’s shoulders, mind; it’s up to his actors to articulate and enunciate, but only Zoe Saldana and Forest Whitaker (respectively playing Russ’s ex and her new beau following the elder Baze’s stint in prison) manage to achieve the miracle of clear speech here. Assume that Cooper bears partial responsibility for the muddy, raspy twangs adopted by the leading men of his cast, but put the rest of the burden on them – they’re the ones trying to affect a specific colloquial dialect with only jumbled precision. They’re capable performers, all, but neither Bale nor Affleck figure out how to make this work; Harrelson gets away with it, mostly, but only because he’s going full-crazy. His peers, meanwhile, aim for soulful and land somewhere in the vicinity of maudlin.

G-S-T Ruling:

To a degree, that feels appropriate: they can’t figure out their characters just like Cooper can’t figure out his movie. Out of the Furnace is colored solely by tonal dissonance, such that when Russell’s quest for retribution begins, it practically comes out of left field. It’s an arbitrary gear shift rather than a logical, organic conclusion to Cooper’s narrative that ends with frustrating abruptness. After a hundred or so minutes of spinning its wheels in a poor attempt at echoing The Deer Hunter, the film simply ends, no coda, no denouement, no nothing. While that’s something of an act of mercy, it’s also a slap in the face; why should we suffer through so much nothing with zip for payoff?