There’s little ingenious, clever, or new about a dark fairy tale; the grisly and the horrific have been hallmarks of such folkloric narratives since the Brothers Grimm put pen to paper two hundred years ago. In that same respect, there’s nothing overtly offensive about them either, at least not at face value, as a veneer of darkness in contemporary fairy tale fare can just be interpreted as a dedication to tradition. Faithfulness to either tone or detail does not comprise one of Snow White and the Huntsman‘s glaring flaws, however; for just shy of two hours, the film tries gamely to assert itself as worthy sword-and-sorcery filmmaking. At times, it even pulls it off, but mostly the picture can only tread water to remain afloat.

If Snow White and the Huntsman can be summed up in a word, it’s “overlong”. In fairness, stories of this sort tend to  demand respectable set-up by their very nature, so when Rupert Sanders, steering the ship, starts his picture off seventeen years in the past with a close iteration of the progenitor tale, he’s merely following protocol. Eventually, he brings us to the point: the evil false queen Ravenna (Charlize Theron), having ruled over the realm of King Magnus since orchestrating his downfall, learns that only Magnus’ daughter, Snow White (Kristen Stewart) has the power to destroy her. Of course, Snow White, resourceful girl that she is, escapes the queen’s clutches, and so Ravenna sends a rough and tumble Huntsman (Christopher Hemsworth) to fetch the girl back.

demand respectable set-up by their very nature, so when Rupert Sanders, steering the ship, starts his picture off seventeen years in the past with a close iteration of the progenitor tale, he’s merely following protocol. Eventually, he brings us to the point: the evil false queen Ravenna (Charlize Theron), having ruled over the realm of King Magnus since orchestrating his downfall, learns that only Magnus’ daughter, Snow White (Kristen Stewart) has the power to destroy her. Of course, Snow White, resourceful girl that she is, escapes the queen’s clutches, and so Ravenna sends a rough and tumble Huntsman (Christopher Hemsworth) to fetch the girl back.

In truth, all of that sounds awfully fun on paper. Surprisingly, some of it even works on celluloid. But the problem lies in getting to the successful bits. Snow White and the Huntsman suffers palpably from Sanders’ lopsided hand at pacing and from a lack of essential editing; the film is much longer than it needs to be, and it feels even longer than that. Clearly the editing bay didn’t get much use here, and so an over-abundance of indulgent, superfluous material winds up clogging the story.

Snow White and the Huntsman‘s sin of excess creates problems of redundancy and necessity. Admirably, the film’s screenplay eagerly strives to make more of its villains and heroes than hollow tropes; in some ways it succeeds. But it also overachieves. Fleshing out Ravenna into a bitter, wronged woman brimming with contempt for men, who use and discard her, proves to be an effective turn for the character. Making the Huntsman a bereaved, guilt-ridden loner allows him to resonate. Yet overstating these points with bullhorn subtlety robs them of power.

Clumsily, the film reminds us of their ennui at every opportunity in the most expository of ways. Sanders forgets that these emotions are so much more effective when they’re allowed to surface through actions rather than words. The film’s bloat originates in more than repetitive character beats, though– entire roles and story arcs that could have been cut without disrupting the primary plot’s advancement. Does Snow White need multiple love interests? Does she need to be destined by the stars and all nature to end Ravenna’s reign? One would think avenging her father and herself would be motivation enough.

In fairness, Snow White is plenty proactive on her own, but the film pilfers its protagonist’s sense of agency at every turn. Maybe that’s somewhat appropriate, given Stewart’s history of playing a certain passive female character, but the reductive brush Sanders paints her with is made no less frustrating by the actress’ other career choices. Snow White and the Huntsman deserves a better-respected heroine.

And it deserves more involving storytelling. Whether he’s letting the plot unfold with all the alacrity of molasses or putting roadblocks in the path of his overarching narrative, Sanders insists on keeping the film in neutral. When Snow White and the Huntsman moves, it’s affectingly magical, but “when” shouldn’t be part of the equation. Even as the film dives into the fantastical without an ounce of context, it’s still more colorful and alive than at any other moment of its 117 minute running time; if only every scene could pop as much as Snow White’s encounter with a white stag in the realm of the fairies. (It’s even stranger than it sounds. Delightfully so.)

There’s a real spark of life to be found in the effects work and design on display here. It’s a shame that Sanders couldn’t mine Snow White and the Huntsman‘s inherent grimness with as much efficacy. Theron and Hemsworth, at least, have fun, the former in particular being a complete hoot; she brings howling melodramatic gusto to every syllable she utters and every move she makes in a role with no room for nuance. Hemsworth, meanwhile, plays roguish and brooding so well that his performance feels more like math than anything else, but he’s emotional and charismatic enough to rise above formula.

But they’re surrounded by either wasted or absent talent. Stewart isn’t terrible here, but that’s almost entirely thanks to her being surrounded by truly capable supporting talents– and nothing can keep her from looking absurd in a suit of armor. Meanwhile, greats like Ian McShane and Bob Hoskins, appearing as two of eight dwarves, barely register courtesy of a dearth of screen time. They do plenty, and yet none of it matters.

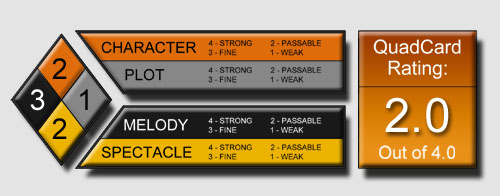

G-S-T RULING:

Ultimately, Snow White and the Huntsman hides behind a sheen of prestige. There’s pedigree here, and, yes, even some wonderful imagery and cinematography to dazzle audiences, but it’s something of a trick; the film has more in common with Alice in Wonderland than Lord of the Rings, though sweeping shots of our heroes traversing countryside are taken from Jackson’s playbook. In fact, Snow White very much reads like a collection of influences rather than an original vision– apart from Jackson, there’s some Scott and Del Toro in here as well. That I’d rather watch any of their films from which Sanders borrows proves to be Snow White‘s Achilles’ heel more than slipshod storytelling and uneven acting.