Did you know about the corrupting influence money can have on a person, or several persons? Were you aware that the pleasures of the high life come at a dark price? The Taste of Money has both of these big, obvious questions on its mind among many others, and the film– the seventh to come from controversial South Korean filmmaker Sang-soo Im– tackles these ideas with melodramatic zeal, never once shooting for anything resembling graceful subtlety in its portrait of South Korea’s wealthy ruling class. Frankly, the film scarcely even seems interested in dealing with reality, instead engaging in brash, lurid mythmaking ripped straight from headlines chronicling the battle between the 99% and the omnipotent elites.

The Taste of Money isn’t really a protest film, mind; it’s more of a scathing indictment lobbed in a salvo of gorgeous filmmaking than it is an articulate political statement. But that shouldn’t be a surprise coming from Mr. Im, whose 2005 opus The President’s Last Bang registers as an inchoate howl of disgust toward South Korea’s third president-cum-dictator, Chung-hee Park, a man who by all accounts deserves few remembrances kinder than what Im chose to offer. In short, if The Taste of Money offends your social sensibilities or strikes you as being so overtly and intentionally broad as to verge on rank partisanship, then Im has made his point.

The Taste of Money isn’t really a protest film, mind; it’s more of a scathing indictment lobbed in a salvo of gorgeous filmmaking than it is an articulate political statement. But that shouldn’t be a surprise coming from Mr. Im, whose 2005 opus The President’s Last Bang registers as an inchoate howl of disgust toward South Korea’s third president-cum-dictator, Chung-hee Park, a man who by all accounts deserves few remembrances kinder than what Im chose to offer. In short, if The Taste of Money offends your social sensibilities or strikes you as being so overtly and intentionally broad as to verge on rank partisanship, then Im has made his point.

Here, the director follows the life and times of the ultra-rich and thoroughly crooked Yoon family as seen through the eyes of its patriarch’s private assistant. Young-jak Joon (Kang-woo Kim) gives us an anchor in the lavish extravagance of the Yoon’s world, though one gets the sense that Im sees the bewildered man as his own personal avatar as much as an audience surrogate. With each iniquity or act of debauchery he witnesses, Young-jak only responds with a curt quip to himself and a determined resignation to move forward and forget; one might argue that he’s culpable in his own way, since he sees all of the Yoon family’s treachery but does nothing to stop it. He’s a silent participant in their perfidious behavior, much like us or, perhaps, Im himself.

Maybe there’s something to that. The excess that the Yoons enjoy is attractive, even if their ceaseless deceptions and insatiable greed aren’t. Part of The Taste of Money‘s pleasures stem from its wanton indulgence in the opulent lifestyle it decries, though none of this is meant to accuse Im of moral or even artistic hypocrisy. If anything, he wallows in the Yoon clan’s affluence to make his point; as these characters enjoy the delights of a sumptuous afternoon picnic on a secluded beach, we become blinded to the details that grant them such luxuries. This is, perhaps, the most profound nuance The Taste of Money has to offer. Money and power can blind people to reality. We at least have the benefit of distance, but there’s no denying how temptingly gorgeous Im makes all of this look.

The real story here, however, is one of self-implosion. Im only delights in the Yoon’s riches in service of building toward their eventual downfall, which he carries out with theatrically sweeping overtures. It’s almost Shakespearean, and in fact key scenes that occur in the film’s final act– you’ll probably recognize them when you see them– feel like they were blocked and choreographed explicitly for the purpose of evoking the ecology of the stage. That actually works to Im’s advantage, affording him the freedom to heighten the dramatics of his narrative without piercing the veil and stumbling over the line from enhanced reality into preachy kitsch; it’s an effective tactic, though one that he doesn’t consistently use to his best advantage.

Case in point: the forced romance between Young-jak and Nami (Hyo-jin Kim), the only member of the Yoon family with a sense of moral decency. Perhaps it’s a given that the two youngest, hottest members of the principal cast should hook up with each other, but Im’s swinging for the fences in every other aspect of his film, and so their union ends up feeling pat. That prepackaged sense of expectation slithers right past his moments of grand theatricality. Of course Nami winds up finding herself attracted to Young-jak; he’s handsome and kind and as upright as his code of loyalty allows him to be, and besides that she kind of deserves a happy ending, even if she is position incorrectly as a supporting character.

Truthfully, Im’s biggest mistake with The Taste of Money lies in the connective tissue that binds it to his last film, The Housemaid. If the former is only meant to be a spiritual sequel to the latter, then the elements that loudly echo between the two feel far too insistent for Im’s own good. Take away those characteristics and nothing about The Taste of Money changes, save that it becomes far more self-contained and self-assured; as is, the film stands up well enough on its own two feet, but the muddled elements between The Taste of Money and The Housemaid undermine its individuality and dilute its incendiary satire.

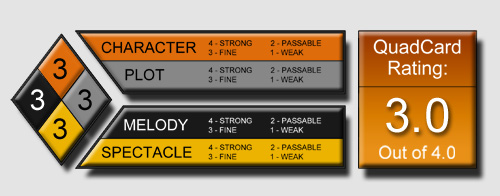

G-S-T Ruling:

But even as Im blurs the dividing lines between the two films, he nonetheless proves why he’s one of South Korea’s most successful provocateurs. While watching The Taste of Money, one gets the impression that on the other side of the lens, Im has an impish grin spread across his face; he relishes every beat he orchestrates, whether it’s a Bacchanal between teams of prostitutes and an unscrupulous American businessman (film critic and cultural gatekeeper Darcy Paquet) or po-faced press conferences punctuated by the flashes of legions of cameras. “Impartiality” doesn’t begin to enter into things. Beneath The Taste of Money‘s exorbitance and avarice, its rampant sexuality and spiritual vulgarity, there runs a current of furious unrest and a determination to hold people like the Yoons accountable for their actions. Occupy Wall Street may be dead, but the spirit it fostered in people the world over remains very much alive.