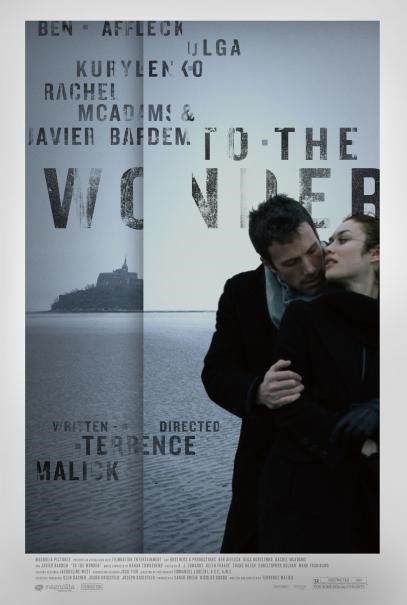

To the Wonder‘s very existence serves as a topic of conversation unto itself, never mind the wholly singular experience of watching Terrence Malick’s cinema. Since when does this man have the gumption needed to make and release two films in as many years? A cursory glance over his working history should prepare even a novice viewer to wait for at least twice that amount of time in between Malick projects, and yet here we are with 2011’s The Tree of Life barely in our collective rear view and To the Wonder looming right in front of us (and two more films, which Malick apparently shot back-to-back, lurking in the shadows for potential mid-decade releases). When did he become this prolific?

To the Wonder‘s very existence serves as a topic of conversation unto itself, never mind the wholly singular experience of watching Terrence Malick’s cinema. Since when does this man have the gumption needed to make and release two films in as many years? A cursory glance over his working history should prepare even a novice viewer to wait for at least twice that amount of time in between Malick projects, and yet here we are with 2011’s The Tree of Life barely in our collective rear view and To the Wonder looming right in front of us (and two more films, which Malick apparently shot back-to-back, lurking in the shadows for potential mid-decade releases). When did he become this prolific?

If the frequency of his creative output has changed, his sense of aesthetics most certainly has not. From the hushed cloisters and tide-kissed shores of Mont Saint-Michel to the spread out lowlands of middle America, from the unbridled joys of familial bliss to the tears of a jaded lover, To the Wonder once again demonstrates Malick’s command over his camera and the landscapes and people he captures with it. Very few filmmakers working today have such a preternatural talent for depicting unadulterated life through a cinematographer’s lens with such gorgeous precision; Malick instills every shot Emmanuel Lubezki takes with purpose and a highly intentional sense of composition, capturing controlled naturalism and pristine beauty in frame after frame.

If the frequency of his creative output has changed, his sense of aesthetics most certainly has not. From the hushed cloisters and tide-kissed shores of Mont Saint-Michel to the spread out lowlands of middle America, from the unbridled joys of familial bliss to the tears of a jaded lover, To the Wonder once again demonstrates Malick’s command over his camera and the landscapes and people he captures with it. Very few filmmakers working today have such a preternatural talent for depicting unadulterated life through a cinematographer’s lens with such gorgeous precision; Malick instills every shot Emmanuel Lubezki takes with purpose and a highly intentional sense of composition, capturing controlled naturalism and pristine beauty in frame after frame.

That may well be the best defense of the divisive auteur’s body of work. It’s stunning to behold on the screen no matter what our individual reactions to his non-traditional, highly elliptical approach to storytelling might be. Here, as in The Tree of Life, Malick employs his traditional poetic, mercurial narrative style, flowing seamlessly from one moment to the next in the telling of his tale. Good news for those confounded and frustrated by his previous effort: dinosaurs don’t ever enter into the picture and we don’t bear witness to the birth of the universe. Instead, we’re anchored between Paris and Kansas and entrenched in the alternately tumultuous and euphoric romance of Neil (Ben Affleck) and Marinna (Olga Kurylenko), though simply boiling To the Wonder down to so simple a categorization as “love story” does it little justice.

In a literal sense, of course, the film is a love story in that it’s a story about love itself. Neil’s and Marinna’s tempestuous relationship gives Malick’s narrative central grounding, but he’s not interested in more typically romantic storybook conceits; we may invest ourselves in the sustainability of their love, but To the Wonder ultimately doesn’t concern itself with garden variety “will they or won’t they” soapiness. In fact, it’s less interested in asking questions as much as it is in presenting ideas and crafting a philosophy of love that’s inspired by the inner musings of its cast, which eventually expands to include Father Quintana (Javier Bardem), a priest struggling with his personal crisis of faith, and Jane (Rachel McAdams), one of Neil’s former flames and his source of comfort when Marinna’s visa expires halfway through the film.

Observing the credits, would anyone be inclined to peg Bardem and Kurylenko as the film’s leads? Affleck and especially McAdams play second fiddle to their European co-stars here, though the raw emotion of love may be To the Wonder‘s true protagonist. One can only imagine how differently the film would play had the positions been reversed. With two ex-pats taking the principal roles, the film becomes one of isolation and alienation from not only the culture which Marinna and Quintana inhabit, but from the feelings of love that they crave. Grant that they’re both after different things; Marinna, utterly alive even at her most sorrowful, needs to feel the more distant Neil’s adoration, while Quintana, a man of the cloth, struggles through his days feeling that he’s been denied the divine, more parental affection of God himself.

So To the Wonder, for the dizzying peaks of artistry it attains, primarily examines spiritual desolation and the fragments of shattered relationships. As in Malick’s other work, the cinematic spaces his characters inhabit serve both to provide them refuge from their suffering and amplify it. A suburban home can be a focal point for a family’s happiness and a lightning rod for its dissolution; a tidal island can nurture fledgling amour and later remind us how far removed from the ups and downs of reality said infatuation really was. Malick infuses the natural world with a reflective quality, too, mirroring the characteristics that define these people the more we come to understand them. (It’s not an accident that Neil, an environmental tester, concerns himself with the toxicity simmering beneath the earth’s surface but proves incapable of pondering the emotions that lie beneath his.)

The real challenge of the film, as in much of Malick’s work, lies in untangling its meaning from its poetic structure; put another way, your mileage may vary, which could very well be a rule for everything Malick creates. To the Wonder is an enigma. Even though it’s so easy to find a common framework within its ambiguities and obscurities, it’s the kind of picture that eludes simple comprehension and refuses to hold its viewers’ hands. Malick doesn’t tell a story so much as present us with the most important pieces of one. In point of fact, that might be To the Wonder‘s greatest distinction- more than any other movie he has shot to date, this one, however the individual viewer receives it (and plenty have piled derision on it to date), has continued the fine-tuning of Malick’s style. It’s a film with no fat, only the barest of essentials.

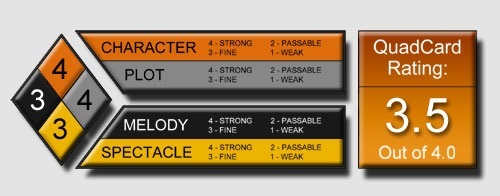

G-S-T Ruling:

And that’s naturally going to leave a number of people feeling frustrated or cheated, but what can anybody expect from Malick at this point? Criticizing him for being obtuse feels akin to criticizing Spielberg for his unabashed sentimentality or Peckinpah for his interest in violence; you’re getting what you pay for, though that’s certainly not to say you have to like it. Given the chance, though, To the Wonder has the power to captivate and spellbind. Maybe it’s his most reticent film to date, but it’s one of his most purely cinematic, perhaps his most visually, evocatively sublime (indeed, Malick’s movies function on completely instinctual, personal levels), and without a doubt one of his most rewarding.

4 Comments

Dan Fogarty

Well, good to see you approve of it. It’s Malick, so it’ll be divisive, no matter. I probably wont get a chance to see this in theatres, but I’ll snatch it up on Blu as soon as I can.

Looking forward to it, I really loved Tree of Life…

Andrew Crump

It’s on VOD bud! Check it out! Don’t hesitate for Blu! (Though I will probably get it on Blu myself.) I’ll be curious to see what you think.

I’m still mixed on The Tree of Life but it’s a good kind of mixed, the kind that calls me back to the film to watch it again. Which I’ll have to do someday.

Colin Biggs

This right here is why I put you down for Best Movie Reviewer on the LAMMY Ballot. Enjoyed reading this, Andrew.

Andrew Crump

Hey, wow- thanks man. Much appreciated!