Good news for fans of World War Z, Max Brooks’ brilliantly crafted mock-oral history detailing the events and aftermath of a worldwide zombie holocaust: Brad Pitt and Marc Forster have made their adaptation of the text in name only. World War Z, Pitt’s misguided attempt at building his very own action franchise through his very own production company, borrows little and less from the source, cherry picking only a handful of moments from a very short list of its innumerable perspectives and locations; readers will immediately recognize the material that made the cut, though the film veers such a sharp left from the book that they may also be left wondering why Pitt and Forster bothered turning to Brooks’ work in the first place.

So really, all of this may read like a death sentence to any dyed-in-the-wool World War Z purist, if such a thing exists. That’s the difficulty in translating a popular, lauded literary work from page to screen: someone, somewhere, is going to feel that something got lost in translation. The problem with World War Z, however, is that everything that makes Brooks’ novel worth reading gets left out, not simply a handful of flavorful but dispensable characteristics. On one level, that’s a good thing; through their differences, both properties remain separate and distinguishable across their respective mediums. Put another way, we’ll always have the book, which is a relief, because the movie is irredeemably horrendous, two hours of bombast and chaos utterly devoid of intelligent thought.

So really, all of this may read like a death sentence to any dyed-in-the-wool World War Z purist, if such a thing exists. That’s the difficulty in translating a popular, lauded literary work from page to screen: someone, somewhere, is going to feel that something got lost in translation. The problem with World War Z, however, is that everything that makes Brooks’ novel worth reading gets left out, not simply a handful of flavorful but dispensable characteristics. On one level, that’s a good thing; through their differences, both properties remain separate and distinguishable across their respective mediums. Put another way, we’ll always have the book, which is a relief, because the movie is irredeemably horrendous, two hours of bombast and chaos utterly devoid of intelligent thought.

Maybe that’s why advanced word of mouth on World War Z pegs it as the perfect summer movie: it practically requires its audiences to check their brains at the door. Breaking from the novel, the film anchors itself to Gerry Lane (Pitt), an ex-UN operative turned retired family man who finds himself smack-dab in the middle of a viral outbreak that transforms its victims into berserk zombies. He’s able to pull enough strings to arrange rescue for himself and his wife (Mireille Enos) and daughters, but not enough to stay out of the action, and soon he’s conscripted for a globetrotting mission to discover the origination of the pandemic and scrounge up a cure.

And so Pitt sallies forth to save the Earth with naught but his wits and a handful of expendable or lightly sketched sidekicks. Pitt’s prominence in the narrative makes sense in light of the production’s overarching goal, yet that only serves to make his lack of presence here all the more mystifying and stifling. From scene to scene, from ordeal to ordeal, Pitt remains inert, showcasing a shocking absence of the charisma that he’s built his career on; he’s stiffer than the undead hordes he outruns. If the film bothered to spend more time developing its supporting cast, Pitt’s apathy might not feel quite so noticeable. As is, he’s a complete drag, and he’s also the only major character in the entire film. Roll that around in your head for a moment or two.

The truth, of course, is that World War Z has bigger problems than a disinterested star. (Though one has to wonder how seriously Pitt wants to be an action hero.) In fact, so many issues both big and small hound the film that treating it as a sovereign entity wholly distinct from the book proves a surprisingly easy feat. Any review could be dedicated to ravaging Forster’s vision on a “failed adaptation” basis, and they wouldn’t be wrong or even without merit; how could anyone mine a blockbuster this thick from a story so rich and complex? How can all of the themes explored and questions raised in three hundred plus pages be excised so easily in the leap from one narrative form to another?

Those questions will frustrate readers familiar with Brooks’ faux-documentary tome, but in truth, World War Z sinks simply because it’s an ugly, dimwitted movie with nothing to offer. For a zombie movie, it lacks that essential ingredient of grue, and for a horror movie, it’s not especially scary. Forster has no experience with either the genre at large or the sub-genre, and it shows; he also apparently doesn’t have AMC, or else he might have learned a lesson or two from The Walking Dead. Uneven though that show may be, nobody can deny the impact it’s had on the archetype George A. Romero sired over forty years ago- zombie fiction can’t get away with being antiseptic and toothless. Maybe bloodshed doesn’t tell a story, but it does supply the kind of base thrills that give zombie fiction its shape. Bereft of viscera and fright, shambling mobs of the living dead become far less intense, and that’s felt in every frame of World War Z.

Of course, this film wasn’t made for zombie aficionados. It was made for the X-Box generation. World War Z feels like a series of missions in standard stealth-and-sneak or survival horror video games, rendering each decision Gerry makes into nothing more than a matter of pushing the right buttons in the right order. There’s no tension or suspense to speak of, just the pressing inevitability that he’s going to run into droves of zombies and escape their undulating CGI grasp (the swarms here function like meat grinders, bloodlessly and efficiently sweeping up passerby). Press X to duck and hide. Press left trigger to crawl. The end of the world has never felt so perfunctorily procedural.

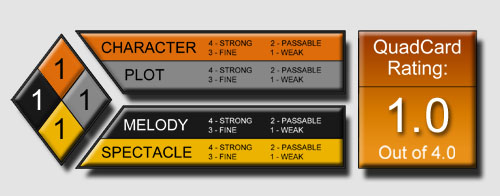

G-S-T Ruling:

Or this episodic. World War Z rolls from one location to the next as Gerry hightails it just in the nick of time and avoid being made into a meal; strangely, the rambling nature of the film leaves it feeling under-stuffed and even small despite its obsession with capturing events on a macro level. That’s almost refreshing in a time where blockbusters are packed with content to the point of overflowing, but World War Z‘s anemia ultimately doesn’t do it any favors. It might not be “epic” like the modern summer movie, but it’s just as tepid and dopey- if not more so.

2 Comments

Colin Biggs

I never would’ve guessed this film would receive such wide-ranging reactions. It seemed like a standard blockbuster template.

Andrew Crump

That’s part of my problem with it: it’s a non-standard story that’s been squashed into a standard blueprint. There’s a way to make that work, but the film takes none of the paths necessary to get there, and instead just makes every stupid decision possible at every turn.