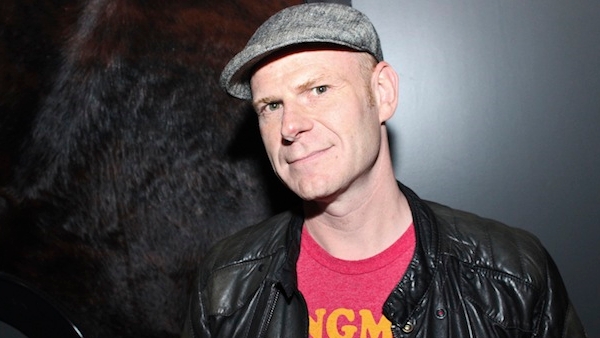

Award-winning composer, Federico Jusid, is a multifaceted artist with many titles including concert pianist, conductor, and film and theater producer. He is best known for scoring the Academy Award-winning Best Foreign Language film, The Secret in Their Eyes, which Federico composed with Emilio Kauderer.

Earlier this year, Federico completed the score for “This Is Us” creator Dan Fogelman’s drama, Life Itself, starring Olivia Wilde and Oscar Isaac. His other recent work includes scoring Spanish dramas such as, Loving Pablo, starring Javier Bardem and Penélope Cruz, A Twelve-Year Night and Ola de crímenes.

Federico recently scored Netflix and BBC‘s re-imagining of the childhood classic, Watership Down. Federico’s orchestral score is accented by electronic sounds and metal instruments which reflect the film’s message of epic sacrifice, tragedy, and human behavior. The producers even took Federico to Watership Down, England to help him connect with the universe of this British classic.

We caught up with Federico to discuss his approach, the instrumentation and overall goal working on this beloved property.

GoSeeTalk: Whenever anyone sets out to remake something beloved by many, it can be a tightrope walk. What was your approach to bring a new sound to this re-imagining of Watership Down?

Federico Jusid: This is not the first time I have worked on a project that had been created before, and the research I did is not only fun, but also very enriching and stimulating. I did a lot of reading and learning, and I spent a whole day walking around the Watership Down in England. But there’s a moment after reading the novel, and talking with the director where you let all that sit and you start writing your own music. All that material that you have absorbed will eventually, and subconsciously become part of your work.

I find it very dangerous to be very self-conscious all the time about everything that has been done before. In a way, it’s like when I write a concert piece and start a string quartet. You can’t help but think of the wonderful string quartets in the works of Beethoven, Ravel and Brahms. It’s very hard to start because those are such wonderful pieces – why would you even dare to start a new one?

But everything you absorb you are inevitably drawing from, subconsciously, at a later point in time. If that reference that you’re drawing on is so heavy on your shoulders, it’s going to affect what you come up with. I’m not saying that it’s good or bad, but its influence has to be true to the story and what you’re trying to do.

Listening to the score, I picked up on a lot of the French horns. Your string work was great, and the scenes where you used violins just came across as tear-jerking. What were the instruments that you wanted to use and wrote music specifically for?

One of the most difficult things on this project was to structure the architecture of this three-hour score to make it somehow coherent and interesting because three hours is a lot of music. The way I structured it was to build on motivic material, and break down the thematic material in the novel like Wagner would do with love, and death, and Efrafa – which is so iconic in the novel – and what the rabbits call the “human warren” which is so alien and threatening for the rabbits.

It’s very unsettling for our protagonists. I used traditional instruments, like you mentioned, but in non-traditional ways. I would knock on the inside of my piano, or have a string performer play with a knife which produces a harshness that mirrors what the rabbits feel when they get close to the human environment. The instrumentation helped, but I put more focus on the thematic material of the novels.

How do you sustain mood over three hours? You can make quite an impact with just two or three notes, but how do you innovate and build on things across a runtime that lengthy?

Very often, it’s much more interesting to say less with music, and let the movie do the rest. Many times you need to get heavier instrumentation. I hope that we have achieved a good balance. Some episodes are heavier on the music, not only having more music, but the amount of dense music with those French Horns and the brass. In other places, like Ep 3, which has a lot of waiting and anticipation, I would say the orchestration is much thinner. I used a lot of string quartets, and a layer of a processed cello that almost sounds like a synth. So I think that dialogue between the density of the music and the density of the story is always very interesting and active. I never take for granted that I have an entire orchestra, and I try to use them all, all the time because they are there.

The beginning of Ep 2 is heart-breaking and more so because your music is emotional. Using instruments in a different way is important like you mentioned, but what was that hollow percussive sound that played as the rabbits tip-toed into the farmer’s garage to rescue the rabbits from the pen?

That was made by a chamber ensemble. Other times we knocked on the wood of the cello or I played a prepared piano – that’s when you put bolts and screws and junk in the way of the hammers, and it creates weird, and unpredictable sounds. With a lot of space in the story, the score gets sparser at the farm. There are moments of vocals where we sing a requiem to human destruction, but there are those elements of devastation and death where instead of doing something terrifying with music, we went for the emotion and the deep sadness of Captain Holly telling the story of what happened to the original warren or the humans’ shooting of rabbits.

The original animated tale was darker, and more violent. This re-telling is toned down, but how do you, personally, build tension? Also, what line is too far for a supposed children’s story?

I come from a filmmaker’s family. It’s something I lived through very early on – in the movieola or the alleyway – and I have seen how many elements go into how film is put together. In my life, I have watched so many films, and learned so much about the process. I think, after 35 years doing this, that you absorb very much of what you’re exposed to. I think tension is created through doing something very big, or on the contrary, it can be built with a layer of one or two instruments.

I think, above all, the main ingredient in tension is being unexpected. If you become too predictable with your score, you lose that tension. As in any other art field, when you fall into a pattern, the audience knows what’s going to happen, and the tension is broken. So your discourse has to be surprising enough to keep you interested and keep the tension going.

But it can’t be so strong that it overshadows what’s going on on-screen. That’s the most important thing. And to be honest, I think kids can take a lot of tension. Whenever I sit with my nephews and see the games they are playing on their PlayStation, I would say that is tension! So I wasn’t afraid of adding too much. I don’t think the music is as crude as the original film. Like I was saying earlier, I think it goes more along with the dramatic and emotional layer of the story.

What were some of the ideas and feedback you received in discussions with director Noam Murro?

We would talk about highlighting the sadness of losing a friend under the hand of humans rather than telling how harsh, or horrific it is to be a rabbit. With film music, you’re always having to decide which point of view you want to take and focus on. In this re-telling of Watership Down, we primarily put focus on the characters.

Talk to us about the symphonies you worked with to create the sound of this score.

For this project, we worked with the Bratislava Symphony, then we had sessions in Budapest and we had sessions at Sofia. We did a little tour of beautiful countries in Eastern Europe. For particular cues and the instrumentation I needed, we decided on different orchestras. Sometimes, for the very broad cues – like the exodus in Ep 1 where they climb the hill and see their future home – it’s a long cue and it’s very uplifting. But for the scene right after, where Clover is locked in the pen at the farm, we went to Bratislava to get that big sound in their huge hall, and we got a lot of warmth and projection from the those wonderful French Horns. The hall is enormous, and that gives you fantastic acoustics for this type of cue. When the rabbits go to the “human warren,” we wanted a different sound and that’s what we recorded in Budapest as well as my studio in L.A.

As a child of the ‘80s, I grew up with the great films and score of that era. In your score, I was reminded of how signature instruments stood out in music by John Williams, James Horner, and Jerry Goldsmith. When you work on a project set in a certain time period, do you study orchestrations of composers’ works from that time?

First of all, thank you so much for the references to those three guys. They are my heroes. I studied orchestration at school for my Master’s degree, and I continue to study orchestration. I read scores but I also go back to classical pieces from Schumann to Stravinsky and his Rite of Spring, right up to Horner and Williams. This is something that I think any composer does all the time – it’s just like going back to the gym to stay fit and stay healthy.

Regarding connecting the score with a particular time, it really depends on the project. I’ve had projects that were clearly period pieces where I had to complement with a color that would resemble a certain area, and a certain time period.

I try not to do that in general to be honest because something that can be very cool, and modern attached to a particular time gets too old too fast. I want my kids to watch this version of Watership Down in ten years, and my wife is pregnant right now, and I truly hope that it doesn’t sound dated to them. That’s why I go for the essentials when I’m telling with music.

Thanks to Federico for his time. His score soundtrack for Watership Down debuts December 21. The mini-series premieres December 22 on BBC One in the UK and December 23 on Netflix in the US. The re-telling of the beloved story stars Nicholas Hoult, James McAvoy, Daniel Kaluuya, Rosamund Pike, and Sir Ben Kingsley among many others, and is directed by Noam Murro.

BBC One’s star-studded new adaptation of Watership Down uses Richard Adams’ bestselling novel as its source to bring an innovative interpretation to the much loved classic. Adapted for the screen by Tom Bidwell and directed by Noam Murro, this tale of adventure, courage and survival follows a band of rabbits as they flee the certain destruction of their home.