Brazil:

Directed by: Terry Gilliam

Written by: Terry Gilliam, Tom Stoppard, Charles McKeown

Starring: Jonathan Pryce, Robert De Niro, Kim Greist, Ian Holm, Bob Hoskins, Michael Palin, Katherine Helmond

Cinematography by: Roger Pratt

Music by: Michael Kamen

Released: December 18th, 1985

Terry Gilliam may possess a degree of prescience, not full-blown clairvoyance but respectable foreknowledge. Then again, studios might just be that predictable. When Gilliam made Brazil, his magnum opus, in 1985, he had in his hands a significant and excellent sociopolitical/cultural satire rife with relevance, a film that skewers the haughty foibles of upper crust society and shines a harsh light on the constricting, stymieing grip of bureaucratic foolishness. It bears mentioning, of course, that his eccentric, bizarre, dark production clocked in at nearly two and a half hours– a dangerous prospect in the eyes of studio executives who tried mightily to get Gilliam to chop the film to pieces and lighten up its ending so as to make it more palatable for consumption by a mainstream audience. (It’s worth noting that Blade Runner, release three years prior, experienced similar roadblocks on its journey to a theatrical run.)

Terry Gilliam may possess a degree of prescience, not full-blown clairvoyance but respectable foreknowledge. Then again, studios might just be that predictable. When Gilliam made Brazil, his magnum opus, in 1985, he had in his hands a significant and excellent sociopolitical/cultural satire rife with relevance, a film that skewers the haughty foibles of upper crust society and shines a harsh light on the constricting, stymieing grip of bureaucratic foolishness. It bears mentioning, of course, that his eccentric, bizarre, dark production clocked in at nearly two and a half hours– a dangerous prospect in the eyes of studio executives who tried mightily to get Gilliam to chop the film to pieces and lighten up its ending so as to make it more palatable for consumption by a mainstream audience. (It’s worth noting that Blade Runner, release three years prior, experienced similar roadblocks on its journey to a theatrical run.)

So it’s worth wondering where would Brazil be without the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Gilliam screened the film for them in private and without Universal’s blessing, and the risk inherent in going behind the studio’s back proved to be worth the danger: his efforts not only earned Brazil the LAFCA award for Best Picture, but also snagged their Best Director award for Gilliam and Best Original Screenplay award for Gilliam and cohorts Tom Stoppard and Charles McKeown. The display of subterfuge finally forced Universal to relent, and so Brazil arrived in theaters in 1985 clocking in at 132 minutes after Gilliam oversaw the cuts needed to make his film fit into a more comfortable running time (comfortable for Universal at least).

Of course, Universal had it right: the public didn’t much care for it, and Brazil wound up being a massive commercial failure. European audiences loved it, but the film feels European (which is only logical given the influence directors like Federico Fellini had on his cinematic style), so perhaps the movie’s lack of success in an American market didn’t come as a surprise to studio executives. But if Universal knew American audiences well enough to rightly fear Brazil‘s chances at the box office, they nonetheless remained ignorant regarding the work of art they had on their hands. It’s not an accident that Brazil remains Gilliam’s most critically celebrated film; from its visual sensibilities to its design and world-building and biting, bizarre, farcical humor,Brazilstands out as one of the most singular, unique films of its decade.

It also happens to be Gilliam’s most personal, most somber, and arguably most purposeful work. Grant, of course, that Brazil follows the same through-line as 1981’s Time Bandits and 1988’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen; it is a film about the power imagination (and together, the three movies are collectively labeled as the “Trilogy of Imagination”), in this particular case about the power it has to free us from the crushing oppressive gloom of reality. Unlike its two sibling productions, though, Brazil operates on a far more intimate level, using its unambitious milquetoast protagonist as a reverse Gilliam surrogate of sorts in order to explore the American Monty Python member’s cinematic world of narcissism, consumerism, and ducts upon ducts upon ducts.

Which is to say that a great deal of credit has to be accorded to Jonathan Pryce for his role in Gilliam’s designs. Despite the fact that even the softest of light reveals Sam Lowry as something of a spineless wimp, the bureaucratic antithesis to everything Gilliam stands for, we come to admire him. That esteem traces back to Lowry’s bold defiance toward the cold, mechanical, authoritarian system that dominates his world, of course, but the character derives much of his heart from Pryce’s sterling portrayal. Every character here gladly– or at least obediently– goes about their daily lives working within the shallow civic parameters set by the Ministry of Information. Sam, on the other hand, dares to dream, and as the film progresses he fights to make his dream a reality.

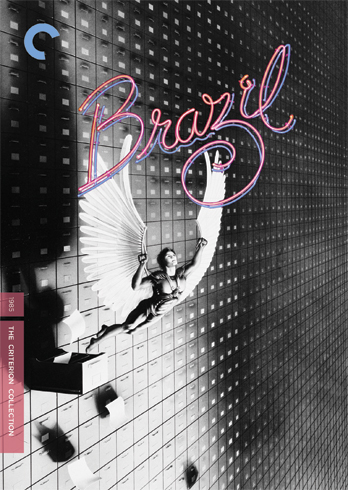

In a way, the very act of indulging in personal fantasy is courageous, so Sam emerges as the bravest character in the film from the film’s beginning. We experience his reveries throughout the entirety of Brazil‘s running time, in point of fact, in which he imagines himself as a gleaming archangel striving to rescue a beautiful woman. It’s a battle that takes him across the skies and through grimy alleyways, putting him into direct confrontation with droves of the huddled, masked masses and enormous robotic samurai; it also comprises enough ofBrazil’s running time to make up its own film, which ends up circling us back around to Gilliam’s central focus on imagination’s function and worth in a society that places no significant value on it.

And that leaves it up to the viewer to determine what Brazil, ultimately, has to say about imagination. Yes, it has meaning and value, but should we consider human imagination to be beneficial or detrimental? In this duct-tangled world, is it Sam who has the right idea about imagination, or do his acquaintances– his mother, his friends, his peers, his superiors– understand that imagination can be dangerous? After all, Sam winds up in the Ministry’s clutches almost entirely as a direct result of his imagination; his daydreams wind up being the thing that ensnares him and leads him to ruin. Are they worth the price of his own destruction?

As the camera pulls away from the catatonic, quietly smiling Sam– dead, or at least driven mad, at the hands of Ministry torturers– and “Aquarela do Brasil” begins playing in the background, the viewer has all the agency needed to draw their own conclusions. But Gilliam portrays the world of the Ministry as one well worth escaping: mired in the most overwhelmingly rank fits of bureaucratic absurdity, its inhabitants exist almost purely for existence’s sake, taking time on occasion to live for themselves and no one else. There isn’t a single redemptive detail in Sam’s life within the confines of Ministry control apart from what he dreams about, and while that life has left him in a vegetative state, nothing that his tormentors do to him can wrest his imagination from him or excise those characteristics which make him who he is– and in that denouement, Brazil and Gilliam champion the power of imagination rather than warn of its dangers.

That’s appropriate for Gilliam; the man is a dreamer himself. Brazil, then, feels like a pronouncement of self, a film about a dreamer battling against red-taped stupidity to see his visions come to fruition. It’s almost autobiographical, and that makes it stand out more than anything else in Gilliam’s body of work.