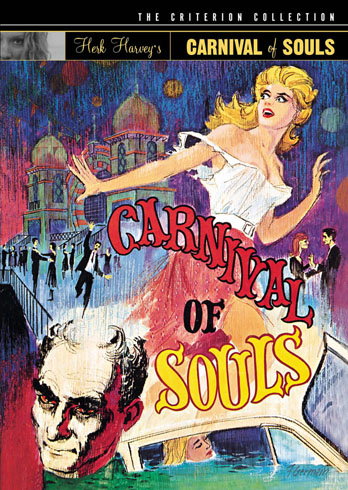

Carnival of Souls:

Directed by: Herk Harvey

Written by: Herk Harvey, John Clifford

Starring: Candace Hilligoss, Herk Harvey, Frances Feist, Sidney Berger, Art Ellison

Cinematography by: Maurice Prather

Music by: Gene Moore

Released: September 26th, 1962

Since starting up the Criterion Files series back in February of this year, I’ve only chosen to analyze and contextualize one film that I’m not one hundred percent willing to champion on grounds of quality. The film in question– The Naked City— by chance happens to be the very first Criterion release I wrote about, one which I identified as being less than impressive; it’s not terrible, but it also doesn’t stand up against the likes of truly great films such as Peeping Tom and Le Doulos. Today, however, The Naked City finds company in Herk Harvey’s 60s cult horror opus Carnival of Souls, an independent movie which blissfully, shamelessly wears that distinction on its sleeve– and, if I’m being honest, fares far, far better than its neighbor despite its warts.

Since starting up the Criterion Files series back in February of this year, I’ve only chosen to analyze and contextualize one film that I’m not one hundred percent willing to champion on grounds of quality. The film in question– The Naked City— by chance happens to be the very first Criterion release I wrote about, one which I identified as being less than impressive; it’s not terrible, but it also doesn’t stand up against the likes of truly great films such as Peeping Tom and Le Doulos. Today, however, The Naked City finds company in Herk Harvey’s 60s cult horror opus Carnival of Souls, an independent movie which blissfully, shamelessly wears that distinction on its sleeve– and, if I’m being honest, fares far, far better than its neighbor despite its warts.

Which are, in a word, plentiful. There’s a tendency to associate the Criterion name with excellence in filmmaking, and for good reason– the Collection houses films from the likes of Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, John Ford, François Truffaut, and Yasujiro Ozu. When your brand houses so many iconic filmmakers under one roof, greatness becomes a baseline expectation. But Criterion isn’t just interested in releasing the best films; there’s an emphasis placed on overall impact and importance in cinematic canon, too, and that more than anything should explain why Carnival of Souls has a place in the Criterion collection alongside the Rashomons of the world. A movie need not be great to be influential.

And Carnival of Souls is undoubtedly flawed. The sound mixing is terrible; high heels clicking across the floor sound like an enormous metronome ticking thunderously in our ears, and dialogue often reads unnaturally. The acting is atrocious; there is literally not a single memorable or even essential performance here outside of that of Candace Hilligoss’ turn as the tormented protagonist. And though getting the job done is hardly a crime, the dialogue spoken from scene to scene ranges from being either too stilted or far too pat. You will not for one moment lose sight of the fact that Carnival of Souls is a film about learning to confront and relinquish survivor’s guilt– Harvey’s script quite brutishly assails us with this notion at every possible opportunity when he’s not putting Hilligoss under the leering male gaze of Sidney Berger’s lascivious alcoholic.

So with all of this in mind, the fact that Carnival of Souls shows so much efficacy in creating mood, sustaining atmosphere, and unnerving its audience is something of a miracle. Harvey’s film is genuinely, marvelously creepy; though the film’s age shows and its carries a dated bag of tricks, the scares work whether they’re false alarms or very real dangers. It helps, of course, that Harvey does all the legwork necessary to make us question what we’re seeing– is Mary merely imagining The Man, the pale, bedraggled specter who stalks her at every turn, or does he truly exist? And how exactly did Mary survive the horrible car crash we witness in the film’s opening frames that took all of her friends’ lives?

When we reach the end of Carnival of Souls, the discovery that Mary didn’t survive that crash may come as no surprise. Whether that’s because Harvey telegraphs the ending or because cinema has borrowed so heavily from the film for half a century makes for a much juicier topic of debate. In fact, that may be Carnival of Souls‘ most prominent claim to fame; the film has been something of a font of inspiration for great, visionary directors since its release in 1962, from Coppola, who replicated the final shot of Harvey’s character in Apocalypse Now; Romero, who has said that he modeled his zombies in Night of the Living Dead on Harvey’s ghosts; and Kubrick, who better-executes a wholly discomfiting shot, in which Mary hallucinates that she’s kissing The Man instead of John, from this film in his own The Shining.

There’s probably a sturdy argument to be made that the worth of Carnival of Souls is found entirely in its unexpected but surprisingly popular influence in 60s and 70s cinema. (And beyond; with its detachment of characters who do not even realize that they’re dead, The Sixth Sense can likely be identified as a potential descendant of Harvey’s film.) If any such case has been fashioned, and I’m sure a cursory search of the world wide web will prove that suspicion to be well-founded, I don’t know that I’d defend against it with much by way of zeal. Carnival of Souls doesn’t qualify as a great film by any stretch of the means, but then most cult pictures rarely do; all told it’s a slice off the independent block and has had a clear, tangible impact on its medium since its release.

But maybe that’s okay. Maybe Carnival of Souls need not be anything more than a film that led other directors to excellent, memorable ideas in their most iconic films. When we start to embrace Harvey’s film from that perspective, Carnival of Souls becomes a much more attractive and charming work than it appears at a glance. If nothing else, it’s a film that commands a certain amount of respect by virtue of the impression it has made on so many filmmakers.

That said, Carnival of Souls has more to recommend it than that; apart from the fact that it is, as I noted earlier, genuinely scary when it wants to be, it’s shot and framed beautifully. You can pick any point in the film and find yourself dazzled by the symmetry of the photography, but Harvey and cinematographer Maurice Prather pay special attention during scenes in which organs prominently feature. Maybe they share a quiet reverence for the massive instruments, or maybe there’s just no way to film them without filming them mathematically and precisely; either way these shots represent among the film’s best, though every viewer is sure to have their favorite images from the film’s crisp, brief running time.

Blending these elements together, then, there’s little room left to doubt Carnival of Souls‘ place in the Criterion canon. How many films can claim to be effective at what they’re supposed to despite their flaws and shot with an impeccable eye for gorgeous composition, while also informing some of the best movies ever made? Amend that: how many no-budget independent cult films can make those claims? Carnival of Souls may not seem like a big deal at first, just a well-made, badly written, ghoulishly fun horror lark, but the power to inspire can’t be taken for granted– and obviously, Criterion doesn’t.