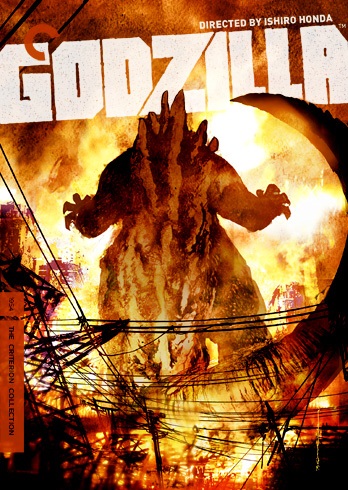

Godzilla

Godzilla

Directed by: Ishiro Honda

Written by: Ishiro Honda, Takeo Murata

Starring: Akira Takarada, Momoko Kochi, Akihiko Hirata, Takashi Shimura

Cinematography by: Masao Tamai

Music by: Akira Ifukube

Release: November 3, 1954

I remember strongly disliking Ishiro Honda’s Godzilla the first time I watched it. Grant that at the time I was both young and unwittingly self-indoctrinated to believe the king of all monsters to be a big, cuddly good guy rather than a metaphor for atomic horror; going from Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster, Godzilla vs. Hedorah, Son of Godzilla, and The Terror of Mechagodzilla to the film that started it all was something of a shock to my eight-year-old system. Defying heritage, I actively favored the latter-day Godzilla yarns in which he played hero to Earth until years went by and I found myself halfway through high school, at which point I decided to revisit Honda’s original film and see if my original child’s evaluation held up.

I remember strongly disliking Ishiro Honda’s Godzilla the first time I watched it. Grant that at the time I was both young and unwittingly self-indoctrinated to believe the king of all monsters to be a big, cuddly good guy rather than a metaphor for atomic horror; going from Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster, Godzilla vs. Hedorah, Son of Godzilla, and The Terror of Mechagodzilla to the film that started it all was something of a shock to my eight-year-old system. Defying heritage, I actively favored the latter-day Godzilla yarns in which he played hero to Earth until years went by and I found myself halfway through high school, at which point I decided to revisit Honda’s original film and see if my original child’s evaluation held up.

Talk about a turnaround. Godzilla goes firmly against a huge chunk of the Toho canon into which the colossal thunder lizard figures, but – ignoring its role as progenitor to every Godzilla film that followed in its wake – it’s by far the best and most important entry in the iconic monster’s screen career, which is a blatant statement of the obvious. Perhaps less glaringly clear is the film’s position as essential post-World War 2 viewing alongside the films of Akira Kurosawa, Stanley Kubrick, and Alan Resnais; their own attempts at documenting nuclear fear don’t go full-silly by sticking a stuntman in a rubber suit and having him stomp around a crudely constructed miniature replica of Tokyo, and for some, the idea of equating Honda’s masterpiece with the works of such lauded filmmakers is likely as sacrilegious as the notion that a man-in-suit monster flick can be described as a masterpiece in the first place.

By now the allegory that defines Godzilla isn’t much of a secret, but it’s worth stressing that the film remains allegorical despite its more fantastical properties. At face value this is just a film about a giant sea monster wreaking havoc on Japan, and observed only in that regard, it’s a wonderful, entertaining slice of cinema. If someone wishes to interpret the introduction of atomic power and scientific experimentation in the narrowest terms possible, then the film because a wonderful, entertaining slice of cinema as well as a cautionary tale about the dangers of meddling with forces beyond our mental grasp. But neither of these perspectives do full justice to what Godzilla meant for a nation still reeling from witnessing the devastation wrought in Hiroshima and Nagasaki firsthand.

Let’s go back to the beginning. In Godzilla, as you may know, nuclear testing performed in the Pacific Ocean awaken a colossal radioactive thunder lizard, the eponymous granddaddy of all kaiju, who rises from the depths and commences rampaging across Japan (primarily Tokyo); he’s big, he’s scaly, and he’s hell on a Geiger counter. At first, Godzilla represents just a minor inconvenience, sinking fishing boats and scaring both island villagers and party boat revelers alike, but it isn’t long before he sets his sights on Tokyo. As repeated military efforts to stop him each fail spectacularly in turn, and as the monster’s incursions on land grow more and more devastating, the film eventually turns to the precise discipline that unleashed him on Japan in the first place – science! – for a solution.

That may actually be one of the most compelling aspects of Godzilla‘s examination of post-World War 2 atomophobia: not so much that it revels in the atomic bomb’s destructive capabilities, though it does do that, but that it does so while directly and indirectly confronting the ethical responsibility behind its use. As Godzilla turns Tokyo into a roiling sea of flames, scientist Daisuke Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata) struggles to keep his latest invention, a weapon known as the Oxygen Destroyer, under wraps even as he’s forced to acknowledge its use as an anti-Godzilla measure. Serizawa, a survivor of the war with the eye patch to prove it, understands he has the means to kill his (and his country’s) enemy, but more than any other character in the film, he’s keenly aware of what that means for Japan and for the world.

When certain doom is tromping toward your homeland, burning and crushing every structure and human being in its path, what do you do? Do you run for the hills and hide, hoping that said doom will grow bored and wade back into the ocean to slumber once more beneath the waves? Do you confront the monster head-on using conventional means? Or do you push the button and engage your own, personal weapon of mass destruction? The very real anxiety at the core of Serizawa’s apprehension is that the rest of the world isn’t ready for the Oxygen Destroyer, and that in the wrong hands it could be used to do real harm to humanity instead of protect it from a prehistoric, radioactive assailant.

By the end, the film appears to accept such catastrophic technology as a necessary evil; Serizawa is convinced to use the Oxygen Destroyer, which successfully defeats Gozilla to everyone else’s elation. But here, Honda makes an interesting choice by having Serizawa commit suicide after winning the day. It’s a chilling moment of self-sacrifice preceded by a scene in which Serizawa burning all of his notes and documentation about the device; he’s ensuring that his research and his knowledge can’t be used to hurt mankind. After essentially committing an act of escalation in an increasingly catastrophic struggle with Godzilla, he makes sure that nobody else will have the opportunity to do the same.

It’s a clear articulation of anti-atomic expression on Honda’s behalf. More to the point, he’s conveying the belief that no one nation should possess a trump card like the Oxygen Destroyer, much less the atomic bomb. Like Serizawa’s terrifyingly brilliant contraption, Godzilla is a force too powerful to be permitted to exist; he can’t be studied or observed, much to the chagrin of archaeologist Dr. Yamane (Takashi Shimura), who as a scientist believes both endeavors to be his obligation. Yet despite the earnest wisdom of Yamane’s sentiment, Godzilla must be stopped and laid to rest at the bottom of the Pacific, and so the doctor’s pleas go ignored. Humanity cannot co-exist with Godzilla’s wrath.

Yet even as the future king of all monsters writhes in his death throes before sinking to his demise, we feel a kind of pity. Ultimately, for all of damage he causes and the lives he takes, Godzilla remains a sympathetic creation, a monster born out of the scientific pursuit of greater knowledge and understanding of the universe we inhabit. Perhaps it’s good fortune that Eiji Tsuburaya elected to outfit Haruo Nakajima with the Godzilla suit instead of using costlier, more time-consuming stop-motion effects; the end result gives the creature a very tangible sense of vitality but also notable elements of humanity. Godzilla may be a menace (to say the least), but he’s the menace that we made through our own folly; in the end, Serizawa’s brave final act may actually be more of a mercy killing than a heroic triumph. It’s another layer of tragedy on top of a film that’s defined by it.