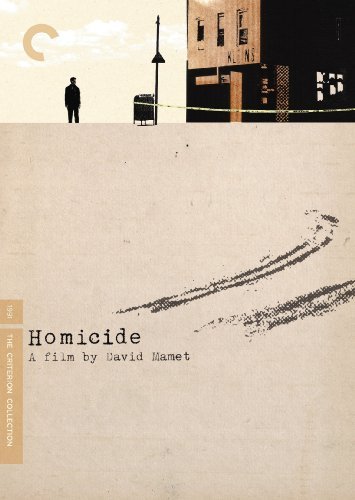

Homicide:

Directed by: David Mamet

Written by: David Mamet

Starring: Joe Mantegna, William H. Macy, Ving Rhames

Cinematography: Roger Deakins

Music by: Alaric Jans

Released: October 9, 1991

David Mamet might today have greater notoriety as a font of controversy and ideological invective than as a filmmaker (and perhaps even as a playwright). Maybe one could argue that that’s merely a symptom of being a conservative convert in an industry dominated by adherents of liberalism, but the more likely cause for his infamy is his own mouth; Mamet’s anti-left wing diatribes could turn even Ann Coulter a bright shade of red. But common wisdom dictates that we can separate the art from the artist, and whatever knack Mamet may have for polemics, his real talents lie in his economy of macho wordplay and his staccato narrative rhythms. In fact, he’s built his entire career by blending together these two proclivities to fashion what essentially amount to cons he plays on his audience.

David Mamet might today have greater notoriety as a font of controversy and ideological invective than as a filmmaker (and perhaps even as a playwright). Maybe one could argue that that’s merely a symptom of being a conservative convert in an industry dominated by adherents of liberalism, but the more likely cause for his infamy is his own mouth; Mamet’s anti-left wing diatribes could turn even Ann Coulter a bright shade of red. But common wisdom dictates that we can separate the art from the artist, and whatever knack Mamet may have for polemics, his real talents lie in his economy of macho wordplay and his staccato narrative rhythms. In fact, he’s built his entire career by blending together these two proclivities to fashion what essentially amount to cons he plays on his audience.

Which makes Homicide something of an anomaly in his body of work. Of course, the film certainly winds in its fashion. There are conspiracies, or more accurately a single conspiracy at the heart of the story, and as Homicide quietly progresses forward Mamet tinkers with its parts and elevates what begins as a boilerplate gritty cop drama into a story about Jewish cabals and a study of personal identity. But the trickery and deception of films like Redbelt and the confidence games of The Spanish Prisoner are conspicuously absent in the tale of homicide detective Bobby Gold; there are secrets, but they neither comprise the purpose of the film nor provide its foundation. In a way, they’re really just incidentals on Gold’s journey of self-realization.

We first meet Gold in the wake of a botched police raid intended to capture Robert Randolph (Rhames), a mainstay on the FBI’s Most Wanted list and a cop-killer to boot. As law enforcement’s efforts to apprehend Randolph are redoubled, Gold comes to stick out like a sore thumb next to his peers; he’s quiet, soft-spoken, nearly laconic in how he chooses his words and when he decides to speak, no small irony given his reputation as an excellent hostage negotiator. By contrast, his partner Tim Sullivan (William H. Macy) does most of the talking and best exemplifies the way Mamet favors the use of language. Sullivan’s speech is brusque and punchy, full of bravado yet informed by genuine care for Gold as a human being and a police officer.

Gold, in turn, doesn’t say much; just enough so that we’re aware of how he personally identifies himself as a policeman. That’s where his loyalties lie. That’s who he is, for lack of a better phrase, and Homicide‘s great conflict eventually arises in forcing Gold to reassess that dearly held sense of identity. Were this Homicide: Life on the Streets, Bobby might have remained on Randolph’s tail, but Mamet has other interests in mind, and through the director’s machinations Bobby ends up following a very different crime in a separate world within the boundaries of his nameless city.

There’s a black irony to the way Gold’s circumstances change and Homicide begins chipping away at his personal identity. Apart from being a detective, Gold also happens to be Jewish, though that hardly seems to matter until he and Sullivan come across a crime scene in a black ghetto while on their way to apprehend one of Randolph’s accomplices. The victim, we learn, also happens to be Jewish; after aiding responding officers, Gold winds up being reassigned to the case at the behest of the deceased’s son, who firmly believes that Gold’s Jewish heritage makes him a better candidate for the investigation. Of course, Gold doesn’t consider himself in terms of his heritage and doesn’t think of himself as being particularly Jewish in the first place; when a superior hurls bigoted invective at him early in the film, it’s Sullivan, not Gold, who acts the most outraged (though Gold certainly is Jewish enough to know what “kike” means).

So Gold’s placement on the case winds up being something of a farce at first. He’s treated with the same incredulity and, eventually, caution as his lack of Jewish identity becomes apparent to the victim’s family members. Gold can’t even read or understand Hebrew or Yiddish. To some of the Jewish characters he interacts with over the course of Homicide‘s running time, this simply makes him an outsider; to some, it makes him something of a cipher. When Gold seeks answers to the crime using what meager evidence he has, he comes across the path of an Orthodox scholar, who shows the beleaguered detective pages out of the book of Esther. Gold’s inability to read and understand Hebrew raises a painful, pointed question from the scholar: “You say you’re a Jew, and you can’t read Hebrew. What are you, then?”

It’s this one simple query that causes Homicide to tilt slowly on its head, and which leads Gold to reassess his identity as a man. Is he a policeman? Or is he Jewish? Gold, once so firmly ensconced in his role and persona as a detective and negotiator, finds himself in a sort-of existential crisis as he delves deeper and deeper into the mystery of the candy store owner’s death and uncovers a conspiracy that leads back to a group of Jewish Zionists. When he comes into contact with them and expresses his desire to aid them, he unwittingly puts himself into a position where he must choose between his newfound sense of Judaic belonging and his loyalty to his fellow police officers.

Gold’s dilemma is still universal even twenty one years after the film’s release, despite the fact that it’s steeped in two very distinct and specific cultural experiences. Today, however, one might perceive Mamet, the man, rather than Mamet, the artist, in this particular element of Homicide‘s story more than anything else. It’s certainly understandable why one might read militant pro-Israel sentiment in the text when nearly a year ago, Mamet published a column in the Wall Street Journal accusing Israel’s left-wing critics of rank antisemitism. As much as Mamet’s politics have changed in the last two decades, though, Bobby Gold– the vulnerable and lost man of words– has remained a constant, a man trying to understand where he belongs and who struggles to reconcile his inherent duality. Whatever political messages can be derived from Homicide in light of Mamet’s recently altered ideological leanings, Gold’s position as the film’s focal point endures.