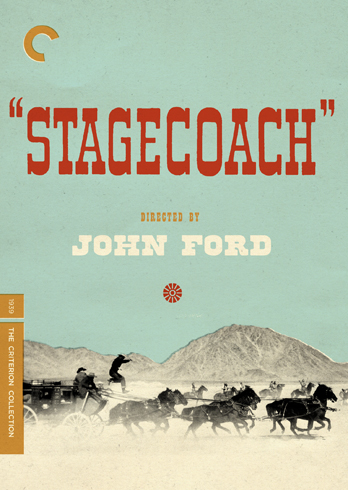

Stagecoach

Directed by: John Ford

Written by: Dudley Nichols, Ben Hecht

Starring: Claire Trevor, John Wayne, Andy Devine, John Carradine, George Bancroft, Thomas Mitchell

Cinematography by: Bert Glennon

Music by: Gerard Carbonara

Release: February 15, 1939

Tag Gallagher once described John Ford as being “essentially apolitical”. Maybe a more accurate term would be “politically mercurial”; at one time in his life, Ford admired John F. Kennedy and staunchly opposed the practices of McCarthyism, while in another he favored Richard Nixon and supported the Vietnam War. Perhaps that was simply his nature as a self-described Maine Republican. What cannot be disputed is that his politics, wherever they fell in any given era of his filmmaking career, informed his films in varied, rich, and interesting ways. In any other case that might lead into a discussion of The Grapes of Wrath, but that lens can be applied just as appropriately to Stagecoach, a film that today reads, of all things, as a partial blueprint for Mitt Romney’s platform in America’s 2012 presidential elections.

Tag Gallagher once described John Ford as being “essentially apolitical”. Maybe a more accurate term would be “politically mercurial”; at one time in his life, Ford admired John F. Kennedy and staunchly opposed the practices of McCarthyism, while in another he favored Richard Nixon and supported the Vietnam War. Perhaps that was simply his nature as a self-described Maine Republican. What cannot be disputed is that his politics, wherever they fell in any given era of his filmmaking career, informed his films in varied, rich, and interesting ways. In any other case that might lead into a discussion of The Grapes of Wrath, but that lens can be applied just as appropriately to Stagecoach, a film that today reads, of all things, as a partial blueprint for Mitt Romney’s platform in America’s 2012 presidential elections.

The key word here is “partial”; Henry Gatewood can’t be painted as the sole basis on which Romney founded his campaign. But there’s a surprising amount of connective tissue in Gatewood’s pontifications about what he perceives to be America’s decline which undeniably links the film to Bain Capital’s co-founder– or at least echoes some of the national discourse surrounding his bid for the White House. America is for Americans; the government has no business interfering with the operation of banks via bank examinations; our national debt is too high; the country requires the services of a corporate officer-in-chief rather than a commander-in-chief. That Gatewood happens to be as full of bluster as his valise is with the $50,000 he stole from his own bank is, perhaps, of no consequence, but doubtless that detail will tickle more ardently liberal viewers who still have a bone to pick with the former Massachusetts governor.

Gatewood’s ultimate fate should be very telling of how Ford himself saw the man as well as the snooty upper-crust society he represents. At the same time, Ford obviously bears no complicity in how modern audiences may read the character, though if anything Gatewood’s belief structure should serve as a reminder that none of the concepts espoused by the contemporary Republican party throughout the election process are new. Indeed, perhaps the most we can take away from Gatewood’s self-righteous hypocrisy here is that Ford filmed Stagecoach at a time in his life when he leaned more to the left on the political spectrum. Maybe such a statement rings false in light of how the film portrays its Native American antagonists as a roving, faceless swarm*, but if Stagecoach paints Geronimo’s Apaches with broad strokes it at least keeps them so far away from our consciousness to avoid any overt offenses.

Of course, Stagecoach remains a very straightforward Western no matter what anyone chooses to mine from it. But that’s the beauty of the film and the genius of Ford’s direction. Stagecoach does not offer anything by way of twists or turns, nothing tricky anyhow, but it does prove Ford’s mastery of the Western genre and clearly identify him as one of its foremost architects. What’s most amazing about Stagecoach is that it inhabits a space which precedes The Searchers, Rio Bravo, How Green Was My Valley, and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, among many of his other classics; audiences and critics alike wasted no time in solidifying the film as a classic, but Ford still had forty films and change left in him even at this particular peak of his filmography. For another director, Stagecoach may have been the pinnacle of their filmography. Today, we know he was just getting started.

Ford visited and revisited the central landscapes and themes of Stagecoach repeatedly throughout the rest of his career, but in 1939 all that mattered was that he’d reinvented the Western and himself in one fell swoop. Prior to Stagecoach, popular consensus associated the “Western” label with rigid to non-existent characterization, studio backlots, and– maybe not to a modern audience– rampant sexism. One ninety minute film changed most of that all on its own, though it would be foolish to say that Stagecoach perfected the Western in the truest sense of the word. What it did do, though, was introduce Monument Valley to the world as a viable filming location– Ford went on to shoot at least a half a dozen other pictures there, and directors from Zemeckis to Leone have all made the pilgrimage there and back to make their own movies. Isolation most likely drew Ford himself there seven decades ago, but it’s Ford’s work that has called other filmmakers to the valley of the rocks in the years since.

Speaking of introductions, Stagecoach also made one Marion Morrison into a very real movie star at a bargain price. John Wayne had spent most of his time in Hollywood languishing in B-movie hell– he’d starred in mostly Poverty Row pictures– but one zoomed-in dolly shot is all it took to raise him out of obscurity and install him as one of the greatest movie stars of all time. Like the rest of the cast, the Ringo Kid cuts a fairly conventional figure– he’s an anti-hero, a noble, misunderstood outlaw– but what makes each character so effective are the transformational interactions they have with one another. Everyone experiences significant change over the course of the story. We’ve come to accept character arcs as being so essential that we take them for granted when they’re gone, and Stagecoach illustrates just how valuable they are when dealing with archetypes.

That lesson also trickles into another one of the film’s more leftist ideals: that the true personality of each passenger aboard the titular covered wagon becomes crystallized through the way they regard Dallas (Claire Trevor). A prostitute we see being run out of town by the so-called “Law and Order League” of Tonto, Dallas’ personal ignominy makes her into a mirror that reveals her fellow travelers to be either compassionately tolerant (such as Doc Boone) or coldly judgmental (such as Lucy Mallory). Arguably, Dallas supplies the film with its centerpiece– without her, much of that aforementioned characterization never gets to occur. Ms. Mallory never learns to overcome her prejudices; Ringo never finds himself forced to make a choice between a better life and his personal vendetta, and that dilution removes any motivation on behalf of Marshal Curly (George Bancroft) to set the Kid free at the film’s end.

Throughout all of this, Ford carefully instills his narrative with a mythological sense of gravity. Stagecoach could well be seen as a character-driven drama about a handful of strangers being forced into an isolated form of civilization, and it is that, but primarily this is an exercise in genre transcendence. Purists might argue against that notion; genre doesn’t need to be transcended. Perhaps, then, the correct phrase is “pulp elevation”. There’s no refuting Stagecoach‘s roots in Western iconography and the value it draws from them, but Ford’s work here showcases how one can make “genre” into something more than a dirty word.

*It’s very much worth pointing out, particularly in light of Quentin Tarantino’s confessed hatred of the man, that Ford not only sought out local Navajo to serve as extras and laborers on the film, but he made it a point to pay them standard Hollywood wages. Apart from that, he saw their characters as being part of the landscape, details that naturally belong and don’t require individualization. Whether that lessens his culpability here or not is up to the reader, but Ford’s relationship with the Navajos bears more complex discussion– and, yes, his portrayal of Indians here is much, much less layered than it is in some of his other films.

4 Comments

Dan Heaton

John Ford is such a fascinating guy. If you haven’t read it, I’d definitely recommend “Print the Legend” by Scott Eyman. It goes through some of the contradictions you describe. Stagecoach is one of my favorite westerns and was such an achievement at the time for the genre and movies in general. Great post, Andrew!

Andrew Crump

YES! I’ve got my eyes peeled for that one, though I also have to finish a few of the other books I’m reading first before I pick up anything new– but your recommendation definitely makes it more of a must-read for me.

I love Stagecoach. I’ll admit that I wrote about it this time because, yes, I got it for Christmas, but also because I’m really just in disbelief over QT’s hatred for the film and for Ford. It’s an outstanding film, and one of my favorite Westerns of all time.

Dan Fogarty

I’ve yet to catch this one, but I want to definitely. I may just pick it up… I’ve asked for it for Christmas two years in a row, but people just arent getting the hint! LOL Glad it meets with your approval… that tells me its definitely a worthy purchase!

Andrew Crump

Technically, you gave me Stagecoach as a Christmas gift this year. There’s irony in there somewhere. Just treat yourself! It’s worth the buy, absolutely, if not because Criterion releases are always spectacular then because Stagecoach is an amazing movie.

I could honestly watch it just for the dolly zoom when we meet Wayne’s character and for the “fording the river” scene, which features one of my favorite all-time favorite shots.