It took me a while to begin writing Minari’s review. As entrapped as I was in its fine and safe depiction of a social setting, at first I wasn’t able to understand the force of its simplicity, the strength in its silent but provoking statement. Sometimes praising comes in strange ways.

Forget about the awards and the social imperatives that continue to arise. This is a straightforward portrayal of a basic fact. However, the definite tone of the film is commendably welcoming. Even though we are dealing with drama, and typically, tragedy sets in in the genre, I remained with a smile from start to finish. And this is something I’m not used to saying with films that take place in a setting of difficult immigration, cultural differences and family based clashes.

Think about this for a minute: when was the last time life hit you with unthinkable violence? And think about how you reacted in that moment. In that answer, there’s a key for understanding what’s behind Minari’s colorful and direct declaration of optimism.

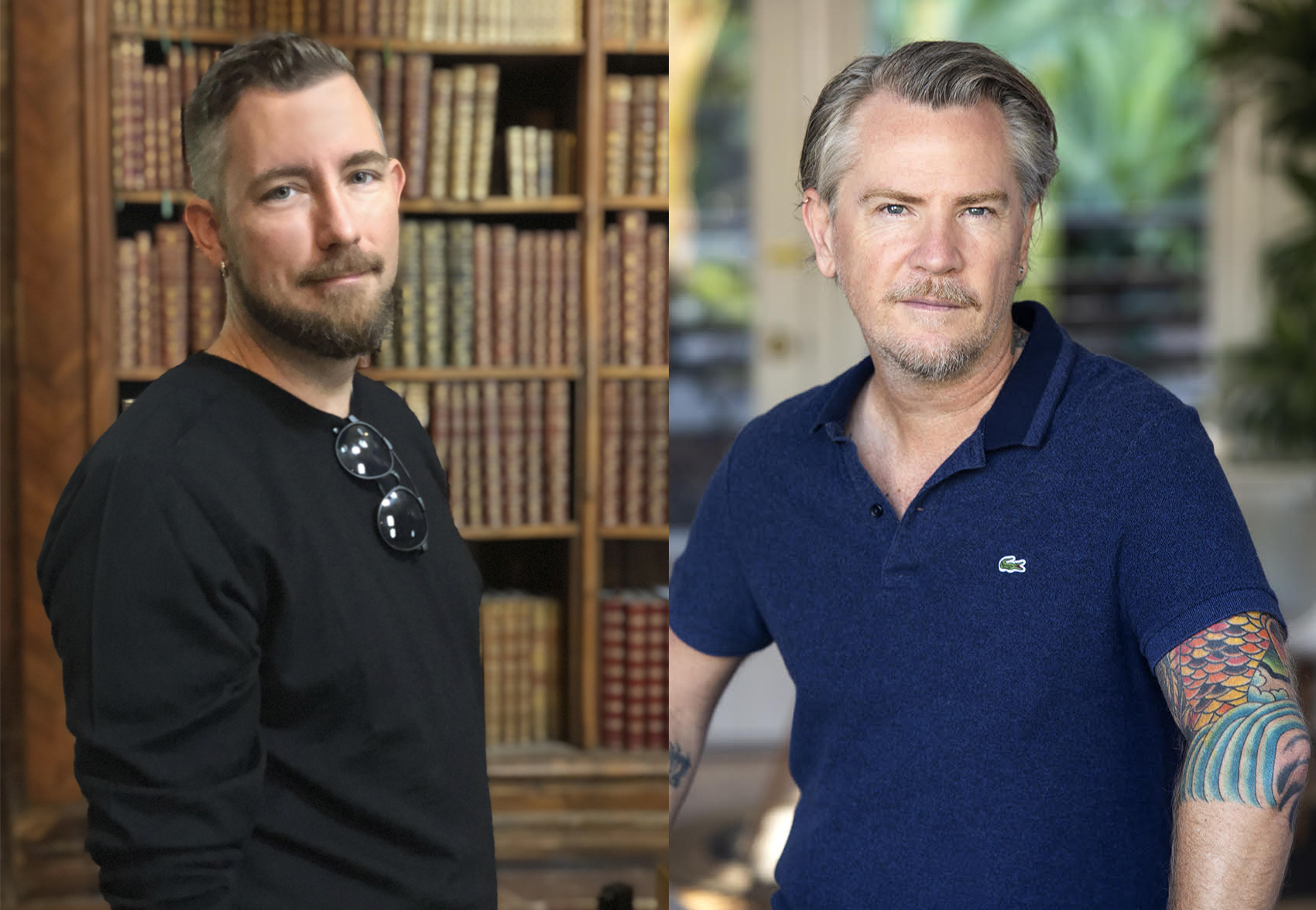

Lee Isaac Chung directs Minari, a semi-autobiographical tale about a family of South Korean immigrants who take a very difficult decision during the 1980’s. They decide to move from the city to a rural town that’s far away from everything they know. Jacob, the father (played by Steven Yeun) hopes he can turn into a farmer and provide for his family. His wife Monica (played by Han Ye-ri) is not as optimistic. Their daughter and son are uncertain.

As the Yis arrive, and understand their decision and the circumstance they’re in, the struggle gets more clear and personal opinions shake the family. Jacob builds an actual farm alongside a very religious companion, but Monica is attached to their past and the idea of “they could have done better”. She decides her mother must come and live with them, so she can help take care of the children while their parents work.

Soon-ja arrives and injects an initial shot from the culture they come from, but as time goes on, the children’s grandmother becomes immersed in the change and through a relationship with David (the boy), a rare bond arises from hope.

Minari is one of those movies with a natural progress that in itself composes a story. Of course there’s something being told in the film and the challenges faced by the family are part of a structured journey. Nevertheless, the film’s narrative value is also composed of a truthful culture that’s not alien to our knowledge. There’s more biographical than fiction in the script, but it’s intelligently blurred in the script.

It’s also a very joyful film, one that’s not easy to forget. Minari is a film that welcomes us to stay. It’s not that it holds us in its grip to discover Asian culture. Its display is more natural and honest. This humble story could feel sluggish, but thanks to a powerful script, Minari is far from a boring coming of age story.

As I thought back of the film, and relived its most interesting scenes of a family revealing itself to hope, I changed my rating. There’s nothing wrong with the film and my only issue with it, seems more like a personal message of curiosity. Minari is a film that stayed with me.

As an immigrant living in far different times than the ones portrayed in the film, you could say it’s farfetched if I relate somehow to the movie’s declaration. But Minari’s wink at the reality of immigration seems more like a helping hand than a pointing finger. Films like that should be celebrated.

Rating: 4/4