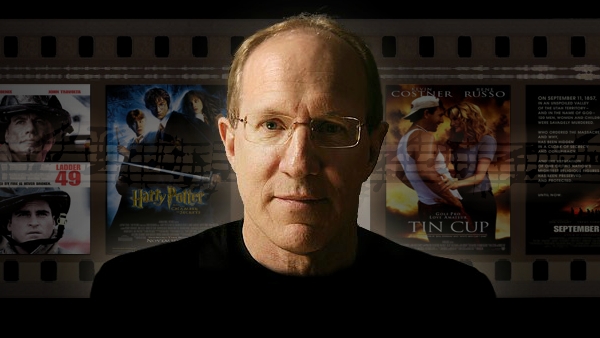

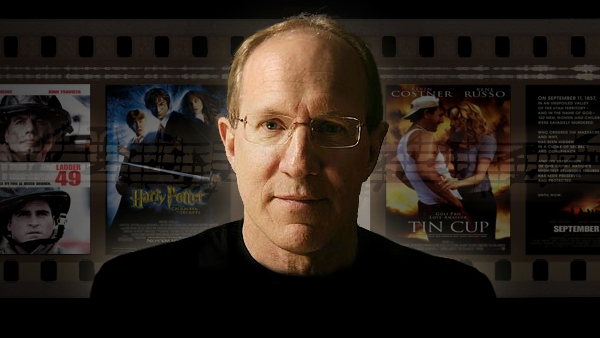

William Ross has had a hand in all avenues of the music industry. A four-time Emmy winner, Ross has decades of experience as a composer, orchestrator, arranger, conductor and music director. Aside from scoring titles like Tin Cup and Ladder 49, he’s worked with a dizzying array of artists and musicians over the years from fellow famous Hollywood composers (John Williams, Alan Silvestri) to pop music icons (Whitney Houston, Michael Jackson).

William Ross has had a hand in all avenues of the music industry. A four-time Emmy winner, Ross has decades of experience as a composer, orchestrator, arranger, conductor and music director. Aside from scoring titles like Tin Cup and Ladder 49, he’s worked with a dizzying array of artists and musicians over the years from fellow famous Hollywood composers (John Williams, Alan Silvestri) to pop music icons (Whitney Houston, Michael Jackson).

Ross has quite a lot of Olympics experience as well as he’s arranged the music for the opening and closing ceremonies for various Olympic games from 1998 to 2010.

But beyond that he’s also tasked with the music of Hollywood’s biggest night. This year’s Academy Awards ceremony marks Ross’ fourth time as music director for the Oscars. Previously he held the role for the 79th, 83rd and 85th Awards ceremonies and was even awarded an Emmy Award in 2009 for his work on the song “Hugh Jackman Opening Number” which was featured during the Awards show in 2009.

GST: You’ve done a lot of orchestrations for various events awards ceremonies and now this is your 4th time as music director for the Academy Awards. So how early on are you asked, what’s the prep time, and what are your first steps?

It varies and a lot of it depends on the producers. This year they are the same as last year, Craig Zadan and Neil Meron, and it depends on what kind of show they’re going for and what they need from me. Normally my first few phone calls are around the end of August or the beginning of September. The producers start talking about general concepts and then we have some kind of production meeting in November where we talk about general things like logistics of working with the orchestra, the number of players in the orchestra, that kind of stuff. It really gets intense right after Christmas and then January and February are like a blur. It’s all very, very intense by that point.

GST: I can only imagine, and with the Oscars being more of an entertainment based award show, as opposed to say the Golden Globes or the BAFTAs, it calls for more of an overly glitzy and glamorous arrangement. So take us from today Friday Feb 24th up to the Oscars and tell us exactly what you’ll be doing on the big night.

WR: Starting this Monday there’s kind of an accelerated schedule leading right up to the Oscars on March 2nd. We

have two full days of rehearsals with the full orchestra. During that time we go through all of the play ons and play offs and all the little bits of music used in the show. We go through that extremely fast. We also have the various talents who are going to be singing, like Pink, come to the studio so we can spend some time with each of them. Then we have our buffer days which are Wednesday and Thursday; we may use those for overflow of scheduling. I know last year we used them both because there was so much music.

Then on Friday we start run throughs where we rehearse the actual show. That’s not really about music but for all the cameras that will be filming from different angles and locations. It’s a choreographed thing for the director who’s looking at the monitors and making decisions on what to do. He’ll call out “Go camera 2″, “Go 5″, “Go Jack Nicholson”, “Go 3″ it’s all very well done and that to me is as interesting a show as the show itself. The directors are so good at telling a story with immediate cuts in live format. They don’t know who’s going to be doing what so they’re just making it up as they go and it’s spectacular, these guys are brilliant.

GST: A lot of your resume is filled with your orchestrations and part of what you’re doing for the Oscars is adapting and reinterpreting music from films of the year in addition to the nominated scores correct?

WR: Right. When I do the Oscars I particularly like the music to be authentic or as close to the original way as possible. Now that’s not always possible, and it doesn’t mean that if somebody does it differently that there’s anything wrong with that but it’s just my personal thing. That being said sometimes the song or theme is really intense or non-traditional, or all synth, and really layered, so you just can’t do that with an orchestra.

So to answer your question I usually reach out to the artists and composers of various scores and if their movie is up for any type of award I like to hear from them if there’s anything they’d like to play. We and the Academy want to be very respectful to everyone involved in the show: artists, directors, composers, talents, studios, etc. so we make sure to prepare a piece of music for all the nominees should they be called to the podium.

GST: I can see right off the bat one of the challenges might be Steven Price’s score for Gravity, which is a hybrid of experimental, atmospheric, and orchestral components.

WR: Yes, Steven checked in and I think we have a nice piece for the night. Again, it doesn’t have to be long— it just has to sell that moment. I think Steven did a great job helping point us in the right direction for what they’re looking for for Gravity.

GST: Is there an official “Oscar Orchestra” or do players change from year to year based on the evening and what you’re intending to do?

WR: There isn’t a specific Academy orchestra per say— the music director has the right to have anybody he or she wants. But the one we have is made of terrific musicians here in LA.

Now, I use pretty much the same musicians for all the things I do. We fill out the woodwinds section a little bit because one of the things we like to do is be able to give it a swinging jazzy feel, or use saxophones for example. At the same time, if we wanted to do legitimate stuff we have the ability to do that too.

One of those woodwind players in particular is an amazing story: his name is Gene Cipriano — we call him “Cip”— and he has been doing the Oscars for, I think he said, 52 years — I am not kidding. One year they showed some clips of Bob Hope doing one of his first Oscars and Cip said “I was there, I was playing that show!” *laughs* I have done this 4 times and here’s a guy who’s done it 52 times. That’s just amazing!

GST: So what number are you at this year and will you be conducting Sunday evening?

WR: I think we’re right at sixty players -same as last year- and, yes, I’ll be conducting everything.

GST: Going back to what you said about the rehearsals, are any of the presenters or stars going to be present at that time, or will there be stand-ins?

WR: We do have a full dress rehearsal when we run through everything, and they encourage the presenters to come by. Then again, this being a live show, nobody knows exactly what’s going to happen and the presenters can come out in different clothes, different hair, whatever… *laughs* I think that’s part of the fun of tuning in!

GST: Now this is Ellen’s second time hosting. Will she be performing, singing/dancing like years past and have you been included on the rehearsals? Or do will she be more like Billy Crystal or Alec Baldwin/Steve Martin?

WR: Interestingly enough, the first time Ellen did it was the first time I did it back in 2007. Back then Laura Ziskin was the producer. As for what Ellen is going to do this year, as you can imagine I have to be really careful not to let anything out…

GST: Say no more William, I understand. Next question! *laughs*

WR: Thanks Marc! *laughs* But as for what you can expect, I think you’ll have a good time! *laughs*

GST: Talk to us about the “wrap it up” music. It has certain notoriety as it is a part of the show and a necessary, I hate to use the word, evil. But you’re on a schedule and things need to run in a timely manner so talk to us about its use.

Can you have some fun with it, are you going to use the “Jaws” theme, or are you going to throw a curveball? Also do you refrain when someone is saying something really important?

WR: Truthfully, that whole thing is very difficult for me. It’s unfortunate that music gets the job of telling someone to wrap it up, making all these people around the world believe that I am the one who is telling the winners to get off the stage. Deciding how long someone is allowed to speak is not my call, that’s really the director and producers who are trying to move the show along.

I am just sitting there with my set of earphones on and they warn me by saying, “Okay let’s wrap it up!”

and “Go music!”. There’s a way of doing it properly and we want to be respectful so we’ll sneak in with something light, and then we kind of build it, and eventually drown them out. As to what we’re going to play, I don’t really know yet— I have ideas, but we’ll see. Whether there will be curve balls, I don’t know— we’re still figuring it out!

In any case, I think it’s hard to blame someone specifically for this. Anyone who is going up there and is still talking when the music is being played has heard many, many times, from the producers, from the Academy, from the Academy President, in letters, in emails, etc. that they really want to keep the show trim and that they have a certain number of seconds allotted to speeches— whatever it is, 45 seconds, maybe a minute— and

they beg them to please be prepared. The winners get constant warning lights: after some time it lights up and says, “Please wrap it up” in green, then in orange, then in red at the end of the allotted time.

So when somebody gets up there and they just start rambling on it’s not as though the director is saying, “Oh, let’s just play them off.” They actually always give them extra time. I always hear the angst in the headphones from the director saying, “What are we going to do? They are going over!”. It’s a complicated thing, and I know the Academy wants to be respectful and the last thing I ever want to do is play anybody off…Trust me!

It’s a tough thing to do and every year we try to figure out if there’s another way to get people off the stage, but you can’t go out there, you can’t touch them, they’re excited and you don’t want to force them in any way…so you can’t use a hook and you can’t use crazy means because it’s disrespectful. That’s why after all these years, the simple piano has been the tool we still regularly turn to.

GST: Well another big event this time of year is the Olympics and you have a lot of experience with that. You’ve been responsible for the opening and closing ceremonies for a number of years so is that any different from putting together a huge event like this?

WR: To be honest, it’s not that different. Whenever you write a piece of music for a certain occasion you look for the emotional arc then once you’ve found it and start writing you have to figure out how to end it all. Sounds simple but that’s always the big challenge and it’s common to everything whether it’s a fanfare, a long form piece of music, or just a single note. It also comes down to context. In the Olympics there’s a certain context; it’s easy to find nobility, the struggle to succeed, and that’s always on display for the whole world to see.

For the Oscars, depending on what’s going on, things might be similar or they might not. I realize that’s very general but there are some commonalities particularly this year as the theme for the awards ceremony is “heroes”— and not just superheroes. It’s a tribute to people who we think back on as being heroes like… well, I don’t want to say them, *laughs*, because they might be presenters, *laughs*, but, you know, it could be Marlon Brando— “I coulda been a contender!”— in the way he handles himself at the end of “On the Waterfront.” That’s a hero. You wouldn’t say that he’s a superhero like Captain America or something…but he’s still a hero and I know that they want to focus the interest in that direction so we will be trying to do that with the music.

GST: Awesome, you know the more I talk to you about this the more I’m getting antsy to see the awards. I kind of wish the Oscars were this Sunday instead of next. But I guess that would be detrimental to your time frame and your preparation right?

WR: Oh! Don’t say that! I need all the time I can get and a full week, trust me.*laughs*

GST: Again, a lot of your professional career was as an orchestrator, and you’ve worked with living legends, aside from yourself being a well respected and sought-after musician, there’s a cooperative relationship between the composer and the orchestrator. I’m in the architecture business and I perceptively see that the composer is maybe more likened to an architect, where his or her vision will ultimately help film carry the narrative arc, and then there’s the orchestrator who is more like the contractor who helps figures out how to make the composer’s visions a reality. Do I have that kind of right?

WR: It’s not really as simple as that. It can be, or can’t be, it really depends on the composer and what he or she needs from an orchestrator. It’s a very complex relationship. I don’t orchestrate anymore—

every now and then I do it for a friend, like when I work with Alan Silvestri. I still work with him because we’re friends, so it’s not really so much that I’m “his” orchestrator. Again, it really just depends.

Some composers are fabulous with the orchestra and they know exactly what they want. So the orchestrator is somebody who really just transfers their notes from the sketch to the big page. There are other composers who may not have that kind of experience with the orchestra. It doesn’t mean they’re not good composers, they just need a different kind of help. So, depending on who the composer is and what their experiences are, an orchestrator can be asked to do any number of things.

Imagine for example somebody who can tell a wonderful story but doesn’t necessarily know how to read or write. It really doesn’t detract from their ability to tell the story itself! But I know it’s a difficult question because people might not know that our world has changed from how it may have been years ago.

It’s not too well known who does exactly what in this industry, which makes understanding it a little tougher. I’ve seen these articles where people say, “this guy doesn’t really write his or her music”, etc… I tend to ignore all that because it’s such an intricate and complex process, you can’t just sum it up in one word or one phrase!

GST: Well I realize there’s a lot of minutia to your work but I was, to use another architectural phrase, “looking at things from 30,000 feet”. But I understand every musician is different, depending on their talents, their background, so I see how you can’t answer it just one way.

Now you’ve worked on a ton of movies and with some all-time greats, like Silvestri, as you say but also the likes of Michael Kamen and Danny Elfman to name just a few. So is there any advice, maybe on a global scale, that you’ve received working on a particular film that you think “man I’m glad to have had that”? Or is there a quote from any movie you’ve worked on that you love, have taken it to heart and applied it in your professional career on a day-to-day basis?

WR: Wow. What a great question. It’s such an important one too. I have global principles that I have learned from being in this business for so long, and I think they have been very helpful to me over the years. I’ve learned from various people like David Foster, Michael Kamen, Danny Elfman, etc. I’ve also learned a lot from Alan Silvestri watching him handle his people and clients. Anybody you work with is going to help you develop ideas of how to do things and not to do things. It’s just part of the process of growing up having the goal to be as good as you can be at anything. So, for me, I think some of my global principles are that if it has my name on it I want it to be as good as it can be.

I don’t ever want to I feel like I have to apologize or say, “If they only knew what really happened!” I want to be able to put a product out there and feel that it’s as good as it was that day when I was writing. That’s why I always try to go the extra mile. I’ve also learned to understand that when people request change it’s not a personal attack.

Directors or producers are entitled to make whatever changes they want because it’s their project. My goal is to collaborate with them and to work through that process and find a way that gets us all to the end with a feeling that it was a good collaboration.

You know it’s funny, you being in architecture can relate to this. People in this business, composing or arranging or orchestrating, whatever, they do their work and then present it to somebody. It’s a process where people can be critical of the product very easily. If you write a cue and present it to a director, sometimes they’ll say, “You know, it’s just not working for me,” and some people might react by saying, “I know way more about music than this director, so why should this director be telling me what to do?”

In a way, they feel that the director should be saying, “Yeah, I understand, okay, let’s go with it, its great!” So, to that, one of my favorite analogies, is: suppose you requested a 2-bedroom, 3-bathroom house and the architect shows you plans for a 4-story walk-up with no basement. Are you, as the architect, going

to say, “I know it’s not what you asked for but this is going to work for you”? And as the client, the person who is going to live in that house, would you take something just because the architect told you he or she knows what’s best for you?

No, you would probably reply, “Wait a minute, I don’t care if I don’t know how to build a house, because I kinda know the house I want to live in!” I use that analogy a lot because I think it illustrates exactly what we do as a composer, arranger, or orchestrator: you’re always dealing with people who may not know as much musically as you do, but they sure know how they feel from the music that you write.

That’s a principle that I’ve learned working with a lot of people and doing the job myself. It’s maybe one of the most important principles to understand if you’re trying to sell music to clients.

GST: Before we finish up I just want to say that I think your compositions for Tin Cup are some of the most amazing works of the late 20th century and rank up there “Rudy“(Jerry Goldsmith) and “The Natural” (Randy Newman) in what I consider the “holy trinity of sports scores”. It really an inspiring and emotional theme that has such reverence for the game.

WR: Thank you! Jerry, Randy, that’s good company to be in.

GST: I know you have to get back to your work, but it’s been a pleasure and a real honor speaking with you. I wish you the best of luck next Sunday.

WR: Well thank you so much. I hope you enjoy the show and let me know what you think.

Thanks again to William for his time. The 86th Annual Academy Awards will air on Sunday, March 2nd at the Dolby Theatre and be hosted by Ellen DeGeneres.

One Comment

Adam Gillström

Superb Interview!!!