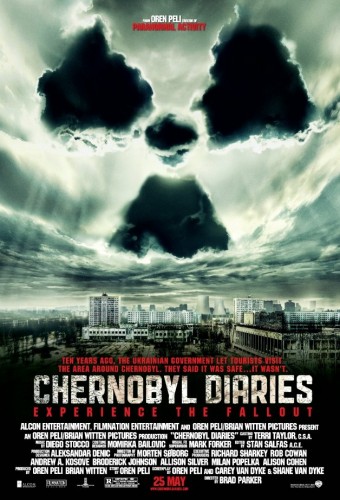

Curiously enough, Chernobyl Diaries may mark the first non-found footage found footage film. While constructed using mostly a straight narrative approach, there’s a nagging sense that this cautionary horror jaunt (penned and backed by Paranormal Activity mastermind Oren Peli) may have actually benefited from more fully embracing the tricky conceit; it’s shot like a found footage movie, it’s crafted like a found footage movie, it scares like a found footage movie, and the title’s reference to “diaries” naturally leads us to conclude that someone, somewhere, came across the footage we’re watching by unhappy accident.

But those eponymous documents are nowhere to be found in an hour and a half of story. Chernobyl Diaries bases its events on a misnomer. The set-up leads a group of young people to Prypiat– the ghost town located nearby the Chernobyl nuclear power plant– on an extreme tourism adventure before stranding them in the abandoned city (or is it?), but there’s nary a moment in the present where any character reaches for a camcorder. In fact the only times the movie goes found footage on us are at the very start of the film, and midway through as a means of conveying the off-screen fates of two central characters. (Which, in a way, feels like a massive cheat, though perhaps not as much as the film’s dubious cinematic geography and passage of time.)

But those eponymous documents are nowhere to be found in an hour and a half of story. Chernobyl Diaries bases its events on a misnomer. The set-up leads a group of young people to Prypiat– the ghost town located nearby the Chernobyl nuclear power plant– on an extreme tourism adventure before stranding them in the abandoned city (or is it?), but there’s nary a moment in the present where any character reaches for a camcorder. In fact the only times the movie goes found footage on us are at the very start of the film, and midway through as a means of conveying the off-screen fates of two central characters. (Which, in a way, feels like a massive cheat, though perhaps not as much as the film’s dubious cinematic geography and passage of time.)

Before I go any further– yes, I’m aware of the inherent oddness in this criticism, given my generally prickly disposition toward found footage as a sub-genre/aesthetic. But found footage can be immensely effective in the right scenarios, and Chernobyl Diaries‘ structures itself in a way that actually supports the approach by giving its characters perfectly acceptable reasons to be filming in the first place. They’ve got their cameras and smart phones out at the ready anyway; a digital camcorder would have represented a completely logical inclusion in their arsenal of recording devices. And when hordes of irradiated Ukrainians fall upon them later, well, they’re already filming, and someone has to play the hero and prove to the world that Prypiat isn’t at all uninhabited.

Now I’m playing screenwriter, which is admittedly kind of cute, but ultimately Chernobyl Diaries‘ problems are rooted much, much deeper in the film’s bones. That doesn’t excuse its superficial flaws– why forgo the found footage gimmick if you’re just going to go ahead and shoot the picture exactly like a found footage picture anyways?– but instead highlights how little they matter in the long run given how messily constructed it is on the script level. We expect that characters in horror films will make bad decisions that lead them into bad and worse situations as the plot continuously escalates (and, as Cabin in the Woods argues, we crave their rank ignorance and foolishness); there are, however, limits to stupidity and ill-advised choices, and Chernobyl Diaries presses far beyond them before it’s arrived at the halfway point.

How many outs can a group of people have? How many times can a movie give its lambs the option of avoiding the slaughter? Repeatedly, Chernobyl Diaries directly acknowledges the inherent danger and risk its characters face as they follow trails of blood to ominous closed doors; it feeds them opportunity after opportunity to evade death (albeit temporarily), and even gives them chances to completely avoid the situation altogether. Characters in horror films are programmed to meander off to their demises, and we’re expected to anticipate them meeting the ends of their lives with excitement, but Chernobyl Diaries hints at their deaths too frequently and with all of the delicacy of a blunt instrument.

As it turns out, that’s kind of a drag. There’s nothing more deflating than constant reminders that brutal doom lurks in the shadows, and Chernobyl Diaries does it with such a high frequency as to appear hesitant and unsure of itself. Part of the fun of horror lies in seeing confidence wane over time. Diaries displays little and less from the outset, and so it shoe-horns in a rushed reference to urban legends about Prypiat remaining home to its residents even after years of radiation exposure. But why? There’s no reason other than to hasten the revelation that said legend is rooted in reality, and with the number of red herrings the film boasts, that confirmation of truth becomes rushed.

In fairness, there’s some moody tension to be found here; the first half hour drops us squarely in the center of Prypiat (though due to safety concerns, director Brad Parker shot in Belgrade), and for a time the film settles into an effectively eerie, haunted gait. In fact, the quiet scenes that unfold in the desolate town stand out as the best in the entire picture. Ravenous humanoids pounding on the sides of a van in the black of night or dragging people off to die painfully only scare us in a flash-in-the-pan manner. We might jump at their quiet but mercurial entrances, but the effect wears off quickly. Meanwhile, there’s innate, lasting terror in the tour of real-life destruction Chernobyl Diaries takes us on. Prypiat exists; if nothing else, the film presents the utter tragedy of its ruin with frank veracity.

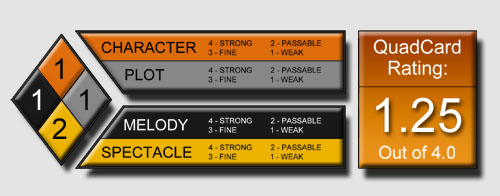

G-S-T RULING:

I wish that confrontation with history had been carried out in service of something earnest and mature. Chernobyl Diaries very much rests; it’s lazy, and it aims for what’s easy. There’s a germ of an idea at the film’s heart that could be worth exploring. Execution notwithstanding, Parker seems at least cursorily concerned with the idea of nature reclaiming the world from man as he attempts to play off of the American fear of winding up lost and defenseless in a foreign country whose residents don’t take kindly to the presence of interlopers. Regrettably, he doesn’t take those concepts seriously enough to intertwine them with adrenaline-fueled horror beats, and invariably, the film winds up a trope-laden and immeasurably dim disaster of its own making.