There’s little use in trying to disguise my frustration with Tom Hooper’s sluggish interpretation of Les Misérables, though in the interest of full disclosure I should acknowledge immediately that I have never seen the musical on which it is based. (And it’s been years since I read Victor Hugo’s original novel.) Put another way, I have no personal ideal of what Les Mis should be, so as far as it concerned me, Hooper– who successfully directed a strong cast of performers to Oscar gold two years ago with The King’s Speech— had the floor here. A shame, then, that he squanders the opportunity by muting his strengths as a filmmaker with melodrama which burgeons beyond his control.

There’s little use in trying to disguise my frustration with Tom Hooper’s sluggish interpretation of Les Misérables, though in the interest of full disclosure I should acknowledge immediately that I have never seen the musical on which it is based. (And it’s been years since I read Victor Hugo’s original novel.) Put another way, I have no personal ideal of what Les Mis should be, so as far as it concerned me, Hooper– who successfully directed a strong cast of performers to Oscar gold two years ago with The King’s Speech— had the floor here. A shame, then, that he squanders the opportunity by muting his strengths as a filmmaker with melodrama which burgeons beyond his control.

You may know Les Misérables‘ story, regardless of whether you’ve cracked Hugo’s text (or skimmed the Cliffs Notes) or watched the play on a live stage– such is the case with veteran narratives of properly iconic stature. Central to the whole saga is Jean Valjean (Hugh Jackman), a Frenchman sentenced to grueling manual labor after pilfering bread to feed his family, as he seeks redemption across nearly two decades and raises himself up from peasantry to respectability; he’s alternately hounded at every turn by the law, exposed to the power of love, and caught in the middle of the June Rebellion as he attempts to evade the ruthless policeman Javert (Russel Crowe) and safeguard his adopted daughter, Cosette (Amanda Seyfried). So, put another way, Les Misérables isn’t just about Valjean– the cast is gigantic, as one might expect of a musical adaptation, and the ways in which they intersect reach soap opera levels of melodrama. Valjean can hardly take a step without tripping over one of the film’s secondary characters, particularly Javert, a man destined to inadvertently find his quarry’s trail no matter the place or the time in which they collide with one another.

You may know Les Misérables‘ story, regardless of whether you’ve cracked Hugo’s text (or skimmed the Cliffs Notes) or watched the play on a live stage– such is the case with veteran narratives of properly iconic stature. Central to the whole saga is Jean Valjean (Hugh Jackman), a Frenchman sentenced to grueling manual labor after pilfering bread to feed his family, as he seeks redemption across nearly two decades and raises himself up from peasantry to respectability; he’s alternately hounded at every turn by the law, exposed to the power of love, and caught in the middle of the June Rebellion as he attempts to evade the ruthless policeman Javert (Russel Crowe) and safeguard his adopted daughter, Cosette (Amanda Seyfried). So, put another way, Les Misérables isn’t just about Valjean– the cast is gigantic, as one might expect of a musical adaptation, and the ways in which they intersect reach soap opera levels of melodrama. Valjean can hardly take a step without tripping over one of the film’s secondary characters, particularly Javert, a man destined to inadvertently find his quarry’s trail no matter the place or the time in which they collide with one another.

None of this, by the way, is so bad on paper; it’s difficult to criticize a work for being precisely what it’s supposed to be, after all, but the problem with Les Misérables isn’t that it plays with such a heightened perception of reality. The problem is that Tom Hooper has no command over the events which he filters through that very veneer. There’s a sense that he firmly has his hand on his picture’s pulse as Anne Hathaway belts out “I Dreamed a Dream” in what easily represents the high watermark of the whole production, but immediately after he ascends that peak, Les Misérables take a drastic turn for the worse when Hooper loses his grip on the reigns; before long the film mires itself firmly in both the worst over-arching cliches of the Hollywood blockbuster and the specific, abrasive tropes of period drama. (If you need to clarify someone’s social status, just look at their teeth and observe the layers of dirt under their fingertips.)

In theory, Les Misérables should have been easy for him, particularly in light of his decision to have his cast sing live rather than have their vocal tracks mixed in during post-production. Hooper is at his best when he’s being non-obtrusive; the peaks of The King’s Speech revolve around wide angles, a motionless camera, and great actors plying their trade unimpeded, and the idea of him working in long, uninterrupted shots to capture single takes for each song is tantalizing on paper. In fairness the best moments of Les Misérables function on similar principles, but at its most exquisite the film just reminds us of Hooper’s limitations as a filmmaker. He doesn’t have a wide range of shots in his repertoire, he’s color-averse, and his style is too beautifully simplistic to pierce the superficial qualities inherent to musicals. I don’t know if that makes Hooper a bad filmmaker, but I’m quite certain it means he’s not well-equipped for adapting Les Misérables to screen.

So the picture feels like a struggle, both for Hooper and for the audience. I deeply suspect that diehard fans of the stage show will be much more inclined toward appreciation of the movie than the uninitiated (such as myself), though I equally suspect that the film’s worst critics will be found among the show’s most ardent fans. Any film adapting a known and well-loved work naturally comes with higher built-in expectations– Les Misérables is no exception. Musical aficionados will have an image in their minds of what Hooper’s interpretation should be, and his film’s success will be predicated entirely on the schism between Broadway and the cinema.

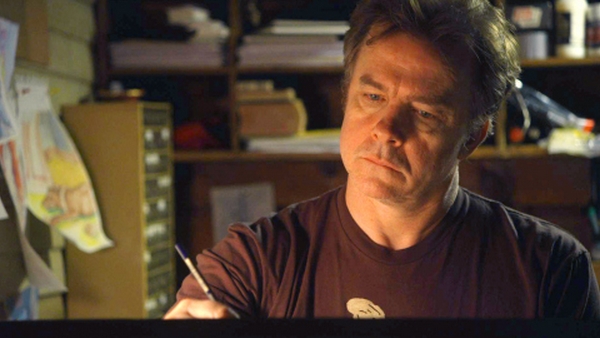

For those of us who lack that level of familiarity, Les Misérables leaves us in an odd place. There’s soul here, at least in the performances of Hooper’s stellar cast, but very little of it translates through aggressive mise-en-scene and cinematography so bad it reaches virtuoso levels of awfulness. Boiled down, Les Misérables is nearly three hours of actors and actresses being stuffed into the corners of camera, losing limbs and sometimes even the tops of their heads in the process as Hooper and Danny Cohen overwhelm them with their presence; it’s embarrassing on a technical level and on a professional level, to say nothing of how much the sloppy craftsmanship threatens to mute the great efforts of the film’s endless supply of principal and secondary characters.

It’s therefore to the credit of Les Misérables‘s cast that their work resonates so strongly as it does. It cannot, for instance, be emphasized enough that Hathway is flat-out incredible; every word you may have heard and certainly will hear about her contribution to the film as we plow forward into awards season is absolutely, utterly true. If any evidence should be offered as to why live singing works, it’s her performance, a marriage of high caliber singing and devastating emotional clarity, but that would be an injustice to her fellow players– notably Jackman, handily reminding us of his Broadway dominance, and Eddie Redmayne, an actor who deserves greater mainstream visibility. Even Crowe avails himself well despite being unable to sing more than a handful of notes, and Sacha Baron Cohen proves again that he’s more than the sum of his endless parade of wacky satirical characters.

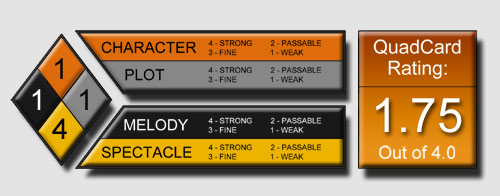

G-S-T RULING:

But it’s not enough. As rousing as “One Day More” may be, as lasciviously fun as “Master of the House” is, as easily as Hathaway breaks our hearts, they’re all acting in the service of the worst kind of Hollywood blockbuster: the kind that possesses absolutely no imagination or vision. We should expect Les Misérables to err on the grimmer side of things, but after a point the entire production becomes unbearably maudlin and gritty, as though the only way to sell the tragedy of the story is to overdress every single thing that appears in frame in woeful misfortune. Given how powerful Hooper’s cast is, less from him may well have been more in the end.

2 Comments

Dan Fogarty

Yeah, you’re right, I suppose. I wasn’t as quick to lay it all at the feet of Hooper, though you’re right, he does nothing whatsoever to elevate this or help its watchability. I thought the material itself was… difficult to translate to a MOVIE, its long, the “songs” are bland with a few notable exeptions, and the story is an unmanageable sprawl…

Wasn’t as fond of Redmayne as you sound, but you’re definitely right that Hathaway and Jackman were both incredible! 😀

Good review Andy, sounds about right to me.

Andrew Crump

Thanks Fogs. Yeah, I’m shocked that it’s getting such a positive reaction from bloggers and critics. Maybe they’re already fans of the stage show. I don’t know, I can’t think of many films I’ve seen this year that were shot more awkwardly and sloppily than this.

Jackman and Hathaway are AMAZING. I wish they were in a movie that honored their efforts, though. I wonder how things would have shaken out had someone with vision and imagination taken the reigns here– even a Baz Luhrmann-type would have wrung a better film out of the material here.