For those of us who weren’t alive in the 60s, the assassination of John F. Kennedy was a very, very, very bad thing for the United States of America, and for the entire world. So bad, in fact, that Peter Landesman took upon himself the task of dedicating an hour and a half’s worth of narrative solely to convey that exact idea. The result of his blunt-force artistry is Parkland, a movie that bursts with promise on the page but never manages to fully live up to its latent potential on the screen; branding the film a total failure would be dishonest, but so too would calling it anything above a partial success.

For those of us who weren’t alive in the 60s, the assassination of John F. Kennedy was a very, very, very bad thing for the United States of America, and for the entire world. So bad, in fact, that Peter Landesman took upon himself the task of dedicating an hour and a half’s worth of narrative solely to convey that exact idea. The result of his blunt-force artistry is Parkland, a movie that bursts with promise on the page but never manages to fully live up to its latent potential on the screen; branding the film a total failure would be dishonest, but so too would calling it anything above a partial success.

Landesman shouldn’t be totally derided for coming up short here – he does, after all, have an interesting conceit in his pocket, even if he lacks an inkling of an idea of what to do with it. Twenty two years ago, Oliver Stone coolly examined the aftermath of Kennedy’s murder with his landmark political thriller, JFK; today, Landesman presents us with an ant’s eye view of the event from the perspectives of the men and women who bore witness to the shooting firsthand. A clever thought for sure, but one that requires shrewder writing, sharper editing, and forty more minutes than Parkland cares to expend sussing out the raw emotions in the chaos following the president’s murder.

Landesman shouldn’t be totally derided for coming up short here – he does, after all, have an interesting conceit in his pocket, even if he lacks an inkling of an idea of what to do with it. Twenty two years ago, Oliver Stone coolly examined the aftermath of Kennedy’s murder with his landmark political thriller, JFK; today, Landesman presents us with an ant’s eye view of the event from the perspectives of the men and women who bore witness to the shooting firsthand. A clever thought for sure, but one that requires shrewder writing, sharper editing, and forty more minutes than Parkland cares to expend sussing out the raw emotions in the chaos following the president’s murder.

Before the first act ends, the film’s cast comes to encompass a staggering number of participants that can best be summarized as “a whole lot”. In point of fact, Parkland might be the most woefully overcrowded movie to grace theaters in 2013; among the involved are the doctors who scrambled to save Kennedy’s life, the FBI and Secret Service agents sent into a tailspin after losing their man, suspected assassin Lee Harvey Oswald’s family (embittered brother Robert and batty, delusion mother Marguerite), and Abraham Zapruder, the poor soul who accidentally caught the entire grisly scene on tape. If Landesman intended on showing the rippling grief felt by a nation following the killing of their leader, he maybe employs one point of view too many.

The problem isn’t the content of each dangling story thread, per se; on their own, the individual accounts all play compellingly, or compellingly enough given the constraints placed upon them by proximity. How is a story about Zapruder, a clothing manufacturer whose life changed irrevocably by his unexpected role in documenting the horrors of November 22, 1963, not interesting? When it’s jammed in between too many other sub-plots for all of the particulars that make it interesting to breathe. Landesman suffocates his own split-narrative, though whether that’s by virtue of time allotted or volume of text is a different matter.

At some point, it becomes prudent to wonder why Landesman didn’t just settle on telling a single yarn. Perhaps he felt that more is, in all actuality, more. Even stretched out to fit a two hour time frame, Parkland would be burdened by overflow; extra footage can only do so much to alleviate problems of cohesion. Try as he might, Landesman can’t get the related yet dissonant elements of his film to harmonize with one another, so we’re left with a film that fights with itself at every chance possible and that somehow never manages to remain tethered to the focal point at its core. (That’s almost a feat in and of itself, but one that’s probably best left alone.)

Frankly, any one of the characters here could have served as the protagonist of an entire movie on their own merits. Zapruder aside, why not make a film about the Oswald family dynamic? In the role of Robert Oswald, James Badge Dale captures a range of complex emotions as the man forever fated to be adjudged as “the brother of the man who shot JFK”; his is the quietest, most nuanced, and single best performance in the entire film, and that’s saying something considering that he’s acting in tandem with the likes of Billy Bob Thornton and Giamatti. The script under-serves all of them, but Dale does the most with what little he’s given as even the reliably great Giamatti struggles to find Zapruder’s center. (His post-shooting outburst could be a career low point.)

That’s not, of course, even scratching the surface of the film’s gallimaufry of an ensemble, which ranges from veteran greats like Thornton, Giamatti, and a horrifically underused Marcia Gay Harden, to greener talents like Zac Efron and Colin Hanks, playing the surgeons who tried in vain to save Kennedy on the operating table. Even Jackie Earle Haley shows up for long enough to offer last rites. Before long, the sheer parade of faces becomes almost kind of an in-joke; even so many celebrities as Landesman brings to muster can’t do much more than hum the film’s central eulogizing refrain. Sure, JFK’s death impacted the fate of the globe; sure, it was sad. But isn’t there more worth saying on the subject than that?

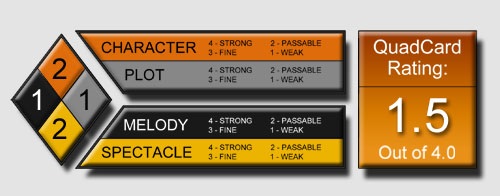

G-S-T Ruling:

Where Parkland works lies in its depiction of hushed human dignity and compassion. During one of the film’s most applause-worthy sequences – Oswald’s burial, cut in juxtaposition to Ron Livingston burning away all evidence of the man’s fateful visit to the Dallas FBI office – Marguerite finally breaks down in tears over her child’s death as Robert bids the journos standing by to help him with the casket. (It takes him much less effort to impel cemetery workers to step forward and help him cover the grave.) Maybe Landesman could have better served his film by honing in on these little moments of humanity rather than attempt to paint a broader vision of the tragedy with the careless strokes he uses here. We know what Kennedy’s death meant to America, but what did it mean to individual Americans? Parkland doesn’t really seem to know.