Thinking about Rise of the Guardians, Dreamworks’ latest offering, I can’t say for sure whether Pete Ramsey mixed a heart-warming, energetic childrens’ film with a story of secular subversion or vice versa. Most likely, it’s the former; there’s little doubting that Rise of the Guardians exists first and foremost to entertain and dazzle theaters full of tykes and adults alike with impressive panache. In that respect, the film succeeds in overwhelming fashion, boasting a bright, colorful visual palette and a much-improved style of animation while giving its world life through excellent voice casting. (If, of course, your concept of Santa Claus involves Jack Donaghy’s Russian half-brother.) Put simply, there’s no denying that the movie’s sense of adventure is its focal point.

Yet Rise nonetheless contains a through-line about man (and children!) questioning the existence of their gods and idols, or at least their faith in them, a detail totally unexpected in a film where the Easter Bunny, the Tooth Fairy, the Sandman, and Santa Claus team up with Jack Frost to fight bad dreams and save the holidays. (Really.) For Rise of the Guardians‘ core audience, the gravity of that particular thread probably won’t register beyond what’s explicitly stated by the film’s characters, so the film remains clearly intentioned as a fun romp through the secret world of holiday avatars and their never-ending struggle to keep wonder alive in children all over the world; that sly, quiet, undermining spirit lingers only in the background. At face value, Ramsey’s story is a heartfelt hero’s journey packed to the gills with great action set-pieces.

film where the Easter Bunny, the Tooth Fairy, the Sandman, and Santa Claus team up with Jack Frost to fight bad dreams and save the holidays. (Really.) For Rise of the Guardians‘ core audience, the gravity of that particular thread probably won’t register beyond what’s explicitly stated by the film’s characters, so the film remains clearly intentioned as a fun romp through the secret world of holiday avatars and their never-ending struggle to keep wonder alive in children all over the world; that sly, quiet, undermining spirit lingers only in the background. At face value, Ramsey’s story is a heartfelt hero’s journey packed to the gills with great action set-pieces.

When Rise begins, we meet Jack Frost (Chris Pine) as he awakens in a frozen lake to the sight of the moon and gradually, awkwardly, and triumphantly masters his winterized super-powers– it’s one of the film’s best sequences– before he’s eventually kidnapped (more accurately: Yeti-napped) by Santa Clause and shanghaied into service as a Guardian of Childhood, a protector of all the good stuff kids get to believe in. Why Jack? Why indeed. It turns out that Pitch (Jude Law), the Boogeyman, has designs on returning the world to a dark, terrifying place of shadow and fear, and the aforementioned Guardians have designs on stopping his designs from coming to fruition. They need Jack’s aid, though nobody can really explain why.

And that’s where the movie’s primary thematic interest lies. Jack, mercurial and child-like, has no center, or at least doesn’t know what his center is; he has no idea what it is that he lives for or represents, unlike his fellow Guardians who all have a comfortable understanding of their purpose and place in the universe. As Pitch furthers his schemes and begins making the lights of the world flicker, Jack strives to figure himself out. This isn’t strictly new territory for Dreamworks– nearly every Shrek film is about self-discovery, but rendered meaningless through anti-continuity– but combining earnest voice acting with the absence of both obnoxious, abrupt pop song-and-dance numbers as well as the infamous Dreamworks face lends Rise of the Guardians much-needed legitimacy.

The film wields that credibility responsibly, weaving an engaging, genuinely fun if very kid-oriented yarn across the abodes of each of its principals– lush Easter Island-themed warrens, snow-capped mountains that look right out of Lord of the Rings, and magical fortresses of both vibrant and gloomy persuasions. Such is the scope of Rise‘s cinematic landscape that there’s a near-immediate curiosity to meet the rest of the world’s holidays and explore their own hideaways (I’m sure I’m not the only one who wants to visit Guy Fawkes Day’s residence); there’s almost no way that Rise won’t get a sequel at some point or another, so I imagine someday we’ll visit these places, which in and of itself might be worth the price of admission– the locations look outstanding, bubbling over with outstanding, eye-catching detail.

In other words, Rise of the Guardians marks a significant and necessary leap forward for one of the world’s animation giants. Dreamworks has suffered diminishing box office returns toward the tail-end of the aughts and hasn’t truly rebounded heading into the new decade. If the film makes any sort of statement, it’s that Dreamworks has realized their usual dog and pony shows don’t work anymore; they need something new. Rise doesn’t pull a complete 180, but in spite of its brilliant exterior and typical collection of bromides the film takes itself seriously and reads like a brand new chapter in the studio’s history. Rise means business– it establishes stakes, presents real, tangible dangers, and almost unilaterally refuses to make things easy on its hero. If the denouement feels sappy and corny (and it does, and it is), the path taken to get there contains respectable hurdles.

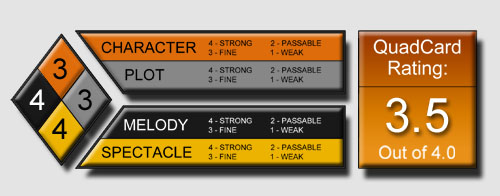

G-S-T RULING:

Among those obstacles is that aforementioned religious subversion, an element that floats so close to the film’s surface that calling it “subtext” feels generous. The Guardians exist at the whim of the Man in the Moon; unlike the rest of the film’s characters, the Man in the Moon has no earthly avatar, hanging silently in the heavens instead. So often in Rise, Jack at first asks and then outright demands truth from the moon, and receives nothing in response. Oh, yes, Santa Claus is real, the Easter Bunny is real, pure evil is real but is the Man in the Moon real? For all intents and purposes, the moon is god– and god, it seems, is dead, or at least frustratingly mum.

I must apologize; it seems that in the end, it is I who got my Nietzsche mixed in with Dreamworks’ kids film. Those ideas– which, along with numerous elements of design, you might trace back to the cheeky, imaginative Guillermo Del Toro, playing executive producer here– aren’t at the film’s forefront, which is far more occupied with delighting its audience. Peter Ramsay has fashioned a wonderful little picture around those ideas, though, an interpretation of belief and “holiday spirit” that reads like something out of Piers Anthony’s rich body of work. It’s alternatingly heavy-handed, sweet, and gentle, but most of all it’s a refreshing turnabout for a studio in desperate need of innovation.