Describing The Act of Killing as a film unlike any made in the medium’s short lifetime almost feels like the definition of hubris, or at least hyperbole. But Joshua Oppenheimer’s wholly unique exploration of the genocidal horrors lurking in Indonesia’s recent history earns every bit of the praise accorded it since making festival rounds this Spring (notably IFFBoston) and beginning its limited theatrical run in July; if critics describe it as a masterpiece, that’s because it is a masterpiece, an exceptional display of daring that will secure Oppenheimer’s name in the annals of cinema. That The Act of Killing also happens to be one of 2013’s most unsettling and insightful releases should simply be seen as a natural result of his achievement.

Describing The Act of Killing as a film unlike any made in the medium’s short lifetime almost feels like the definition of hubris, or at least hyperbole. But Joshua Oppenheimer’s wholly unique exploration of the genocidal horrors lurking in Indonesia’s recent history earns every bit of the praise accorded it since making festival rounds this Spring (notably IFFBoston) and beginning its limited theatrical run in July; if critics describe it as a masterpiece, that’s because it is a masterpiece, an exceptional display of daring that will secure Oppenheimer’s name in the annals of cinema. That The Act of Killing also happens to be one of 2013’s most unsettling and insightful releases should simply be seen as a natural result of his achievement.

And unless there’s an undiscovered gem of documentary filmdom that serves as the hidden blueprint for Oppenheimer’s work, it’s also without a doubt the most singular. Of course, the number of flattering adjectives one could use to describe The Act of Killing has no limit, but perhaps the greatest truism one can make about this gutpunch of a picture is that it’s genuinely one of a kind; complex, moving, disturbing, touching, outrageous, gruesome, gorgeous, and shockingly real even in its most fabricated moments. That alone raises an important question: what kind of doc goes out of its way to engage in pantomime and mimicry? Put simply, the kind that cedes a measure of control to its subjects.

And unless there’s an undiscovered gem of documentary filmdom that serves as the hidden blueprint for Oppenheimer’s work, it’s also without a doubt the most singular. Of course, the number of flattering adjectives one could use to describe The Act of Killing has no limit, but perhaps the greatest truism one can make about this gutpunch of a picture is that it’s genuinely one of a kind; complex, moving, disturbing, touching, outrageous, gruesome, gorgeous, and shockingly real even in its most fabricated moments. That alone raises an important question: what kind of doc goes out of its way to engage in pantomime and mimicry? Put simply, the kind that cedes a measure of control to its subjects.

The Act of Killing turns to sobering events of Indonesia’s past for its basis, succinctly regaling viewers with the details of the anti-communist purge that swept the country between 1965 and 1966. In a smartly articulated recap, Oppenheimer conveys the basics of that atrocity’s aftermath: the nation’s first president was dethroned, the Indonesian Communist Party was overthrown, and an estimated 500,000 human beings – regardless of whether they belonged to that party or not – were exterminated with extreme prejudice. That only scratches the surface, however; one could center an entirely different feature just on an analysis of what incited the massacre, let alone the human abuses committed in its duration.

As much as The Act of Killing‘s roots trace back more than 40 years, though, it concerns itself primarily with the present; Oppenheimer’s point isn’t to chronicle the purge so much as contextualize its barbarisms more than four decades hence. Anchored on the shoulders of the men driving the killings – gangsters-turned-paramilitary-leaders Anwar Congo and Herman Koto chief among them – the film accomplishes two extraordinary feats with shocking ease: first, it gives them the tools and resources necessary to recreate their savagery through a camera lens, and they eagerly dive into the project using their favorite film genres – Westerns, mob flicks, and even musicals – for inspiration. In short order Oppenheimer’s cast become overseers to the telling of their stories.

Second, it invites them to speak freely about the war crimes they committed and reflect on their transgressions as they wish. Perhaps this isn’t much of a victory, though; many of these people quite willingly speak about their monstrous deeds without batting an eye. In point of fact, some of them legitimately believe that they did nothing wrong by persecuting ethnic Chinese or murdering accused communists. As one of Anwar’s fellow executioners argues, the winning side of any conflict gets to decide what constitutes a war crime – and he’s a winner. Fill in the blanks yourself if your gaping jaw isn’t too much of an obstruction. (Though an earlier argument about whether “cruelty” and “sadism” are the same thing may be more of a boggle.)

What’s truly unnerving about this sentiment is that it’s not strictly wrong. Conquerors really do write the history books. At the same time, The Act of Killing represents an alternative to this veneer of power, namely that Oppenheimer’s film has the capacity to expose the truth: that the communists were innocent, and the ruthless death squads of the Pancasila Youth – a paramilitary organization forged in the fires of the purge that even today has its hooks deep in Indonesia’s parliament – were, well, ruthless death squads. Whether it succeeds in that regard or not is another conversation entirely; knowing what the Pancasila Youth are capable of when riled, who would stand up to them? Regardless, seeing these elderly thugs reveal a sober fear that their propagandic mythology could possibly be unraveled presents a modicum of grim satisfaction.

Buffering the movie’s meditations on the nature of tragedy and ethnic/ideological cleansing are its reenactments. Always stylized, they at least bother to maintain a semblance of verisimilitude to begin with; if they’re shot using genre flourishes from the word ‘go’, they at least appear to echo reality. Eventually, these segments come to encapsulate Anwar’s own nightmares, punctuated with smoke machines, ornate costumes, and ham-handed acting, and The Act of Killing takes on a lurid, surrealist quality. Anwar even steps into frame to play one of his own victims, fully embracing Oppenheimer’s basic conceit before his conscience catches up with him and the experiment becomes too much for the old man to take.

Interestingly, Anwar steals the bulk of the film’s focus. He shares the screen, yes, but he’s the closest thing The Act of Killing has to a protagonist; he even has something of an arc, as his guilt stews in the back of his mind for most of its running time before exploding to expressive life in the scenes he helps orchestrate. By the time the film ends, he’s emotionally and physically wracked with remorse over his countless sins. He’s a walking contradiction, a man who personally took 1,000 lives but who chides his grandchildren for hurting a duckling, and that makes him bizarrely magnetic. You’ll want to give him a hug by the end, and you’ll feel like scum for empathizing with a man who drinks, smokes, and cha-chas his way through his golden years without having to answer for the evils he visited upon others in his youth.

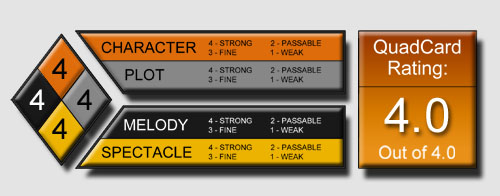

G-S-T Ruling:

Whether that’s part of Oppenheimer’s intent or not is a mystery, though he probably pities the tormented Anwar – the only person in the film to show honest-to-goodness grief and regret over his actions – as much as we do. (It’s worth noting that the Rolling Stones wrote a song whose title fits the particulars of our moral predicament as viewers here.) What’s above dispute is that Oppenheimer has made an utterly bold, endlessly challenging movie not merely about a specific moment of vulgar, unspeakable inhumanity, but about the psychology of why we harm one another. It’s numbing, exhausting, exhilarating, and one of the most necessary films ever created.