High school students of today can breathe a sigh of relief: rather than bother reading F. Scott Fitzgerald’s iconic literary portrait of the Roaring Twenties, The Great Gatsby, they can simply head to the multiplex to have all of its themes and meanings pounded into their skulls for two hours courtesy of Baz Luhrmann. On the surface, which happens to be the only layer his adaptation concerns itself with, Luhrmann has taken everything about Fitzgerald’s novel and distilled it down to its most fundamental truths, and transposed those truths onto film in the most recklessly over-the-top ways possible. Here, disdain for excess is conveyed with the utmost of excesses and not one iota of self-awareness or irony.

But that’s just Luhrmann being Luhrmann. On paper, the idea of Luhrmann adapting a book that revolves around the mass self-indulgence of the era sounds intriguing; if anyone can portray the total sensory overload of Jay Gatsby’s never-ending parties on celluloid, it’s him- in theory, at least. Maybe he’s too successful in his endeavor to bring that culture to life, because by the film’s halfway point he’s totally run out of steam and exhausted the audience in the process. Who knew that The Great Gatsby could suffer from a case of just-too-muchery? Luhrmann ascends to some dizzying heights of slander and sensationalism, but once he reaches those peaks he has no idea how to smoothly climb back down. So he plunges feet-first into the climax and renders his picture comically stilted.

But that’s just Luhrmann being Luhrmann. On paper, the idea of Luhrmann adapting a book that revolves around the mass self-indulgence of the era sounds intriguing; if anyone can portray the total sensory overload of Jay Gatsby’s never-ending parties on celluloid, it’s him- in theory, at least. Maybe he’s too successful in his endeavor to bring that culture to life, because by the film’s halfway point he’s totally run out of steam and exhausted the audience in the process. Who knew that The Great Gatsby could suffer from a case of just-too-muchery? Luhrmann ascends to some dizzying heights of slander and sensationalism, but once he reaches those peaks he has no idea how to smoothly climb back down. So he plunges feet-first into the climax and renders his picture comically stilted.

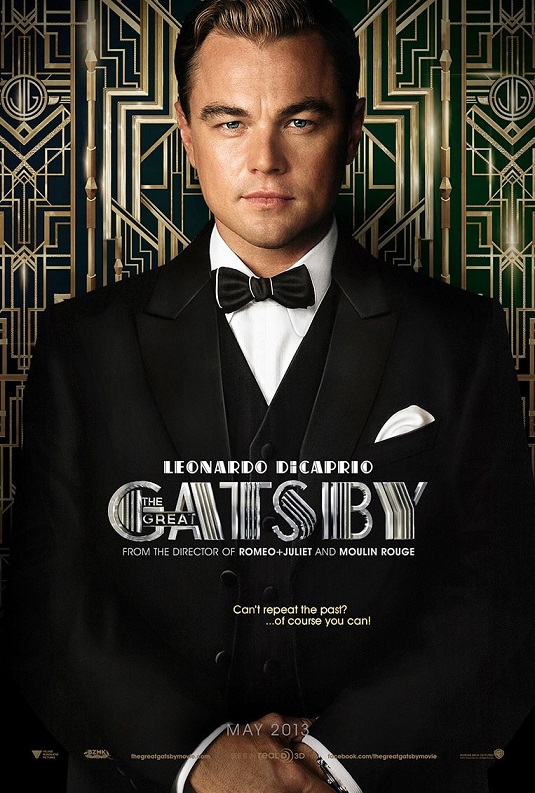

If you’ve never read the novel itself, Gatsby concerns itself with the enigmatic millionaire of the title, a man who strives to keep himself aloof even as he habitually throws extravagant shindigs in his lavish Long Island mansion. We’re introduced to his world through the eyes of Nick (Tobey Maguire), a recent Yale grad attempting to make in the world of bond sales who rents a cottage right smack dab next to Gatsby’s (Leonardo DiCaprio) estate; the former winds up being yanked into the affairs of the latter through chance connections, and before long Gatsby reveals he has an obsession with Nick’s cousin, Daisy (Carey Mulligan). The unraveling of Gatsby’s layers serves as one of the narrative’s two primary interests, the other being social critique of the upper class and 20’s exorbitance.

Of course, the whole thing ends in tears, but you’ll be so overwhelmed by the film’s second hour that you’re unlikely to shed any. Luhrmann treats the entire exercise like a frenetic soap opera; he either rockets from scene to scene or he draws out every beat past its breaking point. Anybody looking for a down-to-earth, realistic interpretation of the text will be completely disappointed, but no one can reasonably expect that sort of thing from the man behind Moulin Rouge. In terms of manic, unbridled celebration, the man delivers, and the moments at which Gatsby soars tend to be those in which the niceties of polite society are shed in favor of an endless stream of alcohol and elaborate festivities.

Make no mistake, this is an often lovely, dizzying film. Colors pop, and while the use of 3D isn’t completely necessary, it does enhance the brightness, the gaudiness, and the vitality of each and every sequence. But when the closing credits start to roll it’s clear that nobody bothered to tell Luhrmann “no” at any point during production. No, subtlety isn’t his strong suit, but there’s a line between being subtle and yanking your audience through a plot they’re almost certainly familiar with on some level or another. If you want the Fitzgerald experience, stick to his original words; if you want the experience of being slapped in the face with a leather-bound edition of the book, watch this movie. After a time, Luhrmann’s blunt, abrasive handling of the story almost feels like audience abuse.

What best (or worst) exemplifies this is the framing device he uses. Ever wondered who Nick is narrating his tale to? Luhrmann has the answer; you may now sleep easier at night. It’s as though he wants to translate the feeling of reading a book onto celluloid, and thanks to his efforts there’s never a moment where you’ll wonder what’s motivating anybody here. Words flit across and pop off the screen all while Maguire narrates his every thought, and while all of those words find their origin in Fitzgerald’s pen, the way in which Luhrmann employs them feels obtuse. Nothing is left a mystery here, and nothing requires an ounce of effort to analyze or consider; you will not have questions about what the notorious “green light” represents by the time the film ends. It’s Cliff Notes-level stuff.

Maybe that’s not a deal-breaker, but it does make for an incredibly forced and inorganic take on a classic story. The Great Gatsby, at times, doesn’t even feel like a real film; it feels like a fake film you’d see people making in a TV show like Entourage, though much, much prettier. At the very least, it can claim the benefit of superior aesthetics and the lunatic energy that defines Luhrmann as an artist, not to mention the saving grace of a great DiCaprio performance. Leo gets the entrance of the film and maybe the entrance of the year, offering a glass of champagne to the audience as fireworks explode in the background. He’s larger than life, as the character should be, never overshadowing the work of his co-stars (save for Maguire, who gets caught up in his own pontificating at times) but always remaining the singular focus of every scene he’s in.

G-S-T Ruling:

Praise should be accorded to Mulligan, who looks and sounds as though she’s right out of the era, and Joel Edgerton, who effortlessly captures self-assured, masculine boorishness as Tom Buchanan. But they’re acting in a film that could have been so much more than it is. The Great Gatsby may be the best adaptation made of Fitzgerald’s novel yet- it’s quite beautiful, and well-acted- but it’s a structural mess that condescends to its viewers.

2 Comments

RidgeRacer4

Completely agree with you Andrew, this did run out of steam halfway through.

Andrew Crump

Wow, thanks bud- glad to see I’ve still got it after all this time.

And I totally agree, this thing is lovely even at its clunkiest. In the end I would have preferred someone with finesse try their hand at transplanting the story to the screen for the umpteenth time, but I guess I can comfortably say that Luhrmann’s vision represents the best movie version of Gatsby ever made.

I just wish that that meant more. At least Leo and Edgerton are on fire. Their climactic square-off is probably the best scene in the entire film.