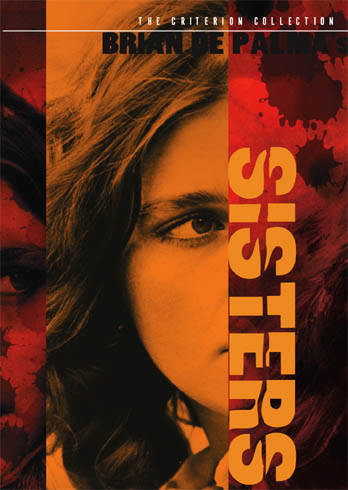

Sisters:

Directed by: Brian De Palma

Written by: Brian De Palma, Louise Rose

Starring: Margot Kidder, Jennifer Salt, William Finley, Charles Durning

Cinematography: Gregory Sandor

Music by: Bernard Herrmann

Released: March 27, 1973

How does a film about voyeurism stand out in the oeuvre of Brian De Palma? By existing as a work of pure, interconnected, voyeuristic thrills. De Palma has been fascinated with the subject for nearly the span of his entire career, and even a cursory glance at his body of work reveals countless pictures into which voyeurism figures as a theme or motif, from obvious entries such as Blow Out, Dressed to Kill, and Body Double and arguably even films like Raising Cain. But among his countless directorial efforts, it’s Sisters that best represents his obsession with the voyeur; the film is practically composed of a voyeuristic cavalcade, a perpetual stream of images into which the act of observation figures.

How does a film about voyeurism stand out in the oeuvre of Brian De Palma? By existing as a work of pure, interconnected, voyeuristic thrills. De Palma has been fascinated with the subject for nearly the span of his entire career, and even a cursory glance at his body of work reveals countless pictures into which voyeurism figures as a theme or motif, from obvious entries such as Blow Out, Dressed to Kill, and Body Double and arguably even films like Raising Cain. But among his countless directorial efforts, it’s Sisters that best represents his obsession with the voyeur; the film is practically composed of a voyeuristic cavalcade, a perpetual stream of images into which the act of observation figures.

In point of fact, Sisters is bookended with portrayals of voyeurism, though of varying degrees of discomfit. If anything, the opening credits– which play out over pictures of infants in utero— should prepare us for the disturbing elements of the last act as De Palma steers his audience straight into the madhouse. That embryonic display comprises Sisters’ introductory frames, and here we’re the voyeur staring directly at life in its most vulnerable stage. Of course, cinema is a voyeuristic medium by its very nature– we, the audience, always play the role of voyeur, monitoring the characters of a film while its events unfold– and our relationship to the film’s first images is no different than our relationship to most any movies that we watch, but it’s a striking way for Sisters to start regardless.

On the other hand, the film’s final shot lets us maintain our role while also serving as an active depiction of voyeurism itself. Dogged and determined, Joseph Larch (Charles Durning) keeps his vigil over the sofa that he is certain contains the body of poor Phillip (Lislie Wilson); he’s perched up on a telephone pole, eyes glue to his binoculars, waiting for someone to come and claim the sofa as it sits idly by a railroad station in Quebec. There’s nothing lascivious about Joseph’s act of voyeurism– it’s actually admirable in its fashion– and yet it is precisely the kind of behavior exhibited by other characters throughout the rest of Sisters‘ running time. Well-intentioned voyeurism is still voyeurism, after all.

And in between the opening credits and Larch’s dutiful watch are countless other examples of voyeurism, perhaps more kindly described as “watching”, in action. Start with the Candid Camera-style television show called Peeping Toms that follows De Palma’s opening credits, which introduces us to Danielle (Margot Kidder), a French-Canadian model and aspiring actress, as well as the doomed but well-mannered Phillip; they’re being watched by viewers at home as well as the live audience, which contains Emil (William Finley), Danielle’s stalker ex-husband who may be more than he appears at a glance. Jump ahead forty minutes and Grace Collier (Jennifer Salt) witnesses Phillip’s murder from the window of her apartment as the dying man attempts to summon help. We’re even treated to an intimate look into Danielle’s memories in the film’s last act. The thrust here is simple: with its deeply probing camerawork, Sisters is nothing if not a deep-rooted and all-encompassing examination of the many faces of voyeurism.

At the same time, Sisters‘ qualities of surveyance don’t represent its only remarkable characteristics. In fact, Sisters serves as the turning point in Brian De Palma’s career in which he transitioned from Brian De Palma, director of documentaries and subversive underground comedies, to Brian De Palma, child of the Hitchcock school of filmmaking, peerless technician, and master storyteller; it’s a clean break from the work he did in the preceding years, and a step forward in his evolution as an auteur of the perverse and the unsettling. No single scene in his filmography up to the date of Sister‘s release goes to such weird, disturbing lengths as the dream sequence in which Emil, revealed as Danielle’s doctor as well as her lover, hypnotizes Grace and she hallucinates episodes from Danielle’s life as a conjoined twin to her sister Dominique.

And no film from his preexisting body of work features such lurid, graphic violence as Sisters does. De Palma was no stranger to violence at this point, of course– the transgressive, experimental, controversial, and brilliant “Be Black, Baby” sequence from 1970’s Hi, Mom! is riddled with violent language and action as a white audience willingly goes through with performance art in which they are painted in black face and harassed, abused, raped, and terrorized by black performers in white face. But Hi, Mom! doesn’t invoke echoes of giallo films, while Sisters feels almost downright slasher-esque in its depictions of bloodshed and death.

The list goes on. As exploitative and dark as Sisters becomes, De Palma still finds space for his macabre brand of humor, and he builds his picture on a platform of high-end craftsmanship. Who else could mine laughs out of a crime scene investigation by dropping a birthday cake– the only shred of evidence Grace finds in Danielle’s apartment– right on the feet of the detective scouring the area for clues? What film feels this grimy and discomfiting and yet still displays cinematic wizardry in the form of the split-screen techniques that have since become one of De Palma’s trademarks?

Maybe the most key attribute of Sisters, though, is its study of duality. Danielle’s multiple personalities– brought on by Dominique’s passing in the wake of their detachment–serve as something of a character template for De Palma’s later films, from Raising Cain to Body Double to Obsession; in each of these, De Palma binds two separate people together under one guise, sometimes more, whether it’s John Lithgow’s mentally fractured psychiatrist and his numerous split personae or Geneviève Bujold standing in as Cliff Robertson’s late wife and a mysterious woman who looks exactly like her. In other words, that quality of “two-ness” we see in Danielle resonates throughout the rest of De Palma’s career, which underscores the importance of Sisters as it concerns the rest of his résumé; it is, put simply, the celluloid blueprint which he has most consistently drawn upon for more than thirty years.