Good news for Americans traveling abroad: you no longer have anything to fear from suspicious, secretly vicious locals. Now you just have to watch out for cataclysmic natural disasters and falling debris, which conveniently bring out the bloodthirsty maniac and paranoid xenophobe in everybody. Basically, if traveling to another country seemed dangerous before, it’s even moreso now, but that’s only because Aftershock has no idea what kind of movie it wants to be, or even how to be it. Is it about Americans being menaced in a foreign land, or is it about how much mankind lives at the whim of shifting tectonic plates? Either way, it’s not particularly good, so it probably doesn’t matter.

The film comes from Nicolas Lopez, who directed a script penned with the aid of Eli Roth. Roth’s involvement here almost suggests that horror cinema has almost moved on from Abu Ghraib; the man behind the Hostel films (well, the first two made before the third went directly to DVD) helped jump-start a genre resurgence of stories about hapless Americans visiting other countries and being mutilated by sadistic torture-hounds. Here, no Elite Hunting club lurks in the shadows, waiting for the right time to strike; in fact, Aftershock plays out more like a party movie in its opening twenty minutes as a nameless man referred to only as “Gringo” (Roth) tours Chile with his friend, Ariel (Ariel Levy) and Ariel’s pal Pollo (Nicolas Martinez). They go to wine country, they go clubbing, they fruitlessly try to help Gringo get lucky; you could see the picture going in the direction of The Hangover before the earth shakes and everything changes.

The film comes from Nicolas Lopez, who directed a script penned with the aid of Eli Roth. Roth’s involvement here almost suggests that horror cinema has almost moved on from Abu Ghraib; the man behind the Hostel films (well, the first two made before the third went directly to DVD) helped jump-start a genre resurgence of stories about hapless Americans visiting other countries and being mutilated by sadistic torture-hounds. Here, no Elite Hunting club lurks in the shadows, waiting for the right time to strike; in fact, Aftershock plays out more like a party movie in its opening twenty minutes as a nameless man referred to only as “Gringo” (Roth) tours Chile with his friend, Ariel (Ariel Levy) and Ariel’s pal Pollo (Nicolas Martinez). They go to wine country, they go clubbing, they fruitlessly try to help Gringo get lucky; you could see the picture going in the direction of The Hangover before the earth shakes and everything changes.

But not for the better. Many horror movies play out like games of chess, where the filmmaker moves his cast from place to place just to get them in a position to die horribly; arguably, that’s their charm and a huge reason why we watch them. Aftershock progresses in that exact vein, except that Lopez doesn’t have the chops to make the mayhem interesting or even the courtesy to make his horror elements resonate with us. An earthquake movie backed by Eli Roth shouldn’t be boring; Aftershock, inexcusably, is a chore to sit through even at 80 minutes. It’s not that Lopez wants to have his schlock cake and eat it too; it’s that his movie is terrible and hopelessly misguided.

Fundamentally, Aftershock should be frightening. Whether or not we’re past the gleeful depictions of slow, tormented butchery that took up so much of horror’s focus in the aughts, recent events ranging from the devastation faced by Japan in 2011 and Haiti in 2010 (not to mention a quake that struck China just last month) should still be fresh in our minds as potential boogeymen. Horror films do, after all, tend to reflect the fears of the times they’re made in, so theoretically, Aftershock could have hit the timeliness sweet spot. The Impossible managed to do just that, and that film came eight years after the tragedy it depicts; there’s no reason Aftershock can’t do the same, even though it’s a B-grade horror movie.

Except for one towering problem: Lopez isn’t a good filmmaker. Earthquakes, apparently, aren’t terrifying enough when you’re a stranger in another person’s land, so we get a mass-scale prison break (which we don’t even see) and the threat of roving street gangs, who seem to have nothing better to do when the world is collapsing around them than rape and plunder. Maybe that’s meant to be realistic; maybe when social order crumbles, people immediately resort to following their baser instincts. Who wouldn’t go a-looting in the face of Armageddon?

The simple answer to the posed query is a resounding “nobody”, as even a cursory glance at human behavior in many of the real-world situations Aftershock riffs on suggests that Lopez is out of touch. Catastrophe, at least as far as recent history shows, has the effect of bringing people together rather than dividing them; if Lopez wanted to examine the ways we act when life is turned violently upside down by forces outside our control, he probably should have paid attention to the news. Clearly that wasn’t his intent, and in fairness there’s no rule stating that Aftershock portray the strength of human brotherhood and spirit in the face of unreal trauma and untold loss.

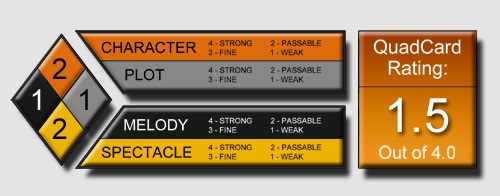

G-S-T Ruling:

But if Lopez wanted to make a film about the human element of calamities like this, he could have gone much less obvious routes than he does here. At the very least he could have had the decency to make a fun, gruesome lark, but Aftershock feels almost antiseptic no matter how many people he crushes beneath chunks of concrete. That’s saying something for a movie featuring two sexual assaults on the same female character, but it’s ultimately a reflection on Lopez’s skill behind the lens: taking the path of least resistance, he still doesn’t have the chops necessary to make even something as awful as that feel really, truly unsettling. Maybe the most disturbing thing about Aftershock offers is the notion Lopez thought any of this would actually work on even a half-seasoned horror audience.