Frank Hvam and Casper Christensen, the stars and writers of Denmark’s Klown, should find themselves in good company among the most prominent members of the raunchy comedy pantheon. Alternately, the remorselessly profane Danish duo might repulse their peers just as easily. Klown, the cinematic evolution of the television show Hvam and Christensen created and featured in together for four years, pushes every boundary of good taste with a smirk and a cackle; there’s gleeful deceit to how the film frequently builds toward redemptive kindness before pulling the rug out from under our feet. But if the film’s primary interest lies in taking the mickey out of Frank, Casper, and the audience, its heart nevertheless remains genuine even through the vagaries of its misguided heroes.

Frank Hvam and Casper Christensen, the stars and writers of Denmark’s Klown, should find themselves in good company among the most prominent members of the raunchy comedy pantheon. Alternately, the remorselessly profane Danish duo might repulse their peers just as easily. Klown, the cinematic evolution of the television show Hvam and Christensen created and featured in together for four years, pushes every boundary of good taste with a smirk and a cackle; there’s gleeful deceit to how the film frequently builds toward redemptive kindness before pulling the rug out from under our feet. But if the film’s primary interest lies in taking the mickey out of Frank, Casper, and the audience, its heart nevertheless remains genuine even through the vagaries of its misguided heroes.

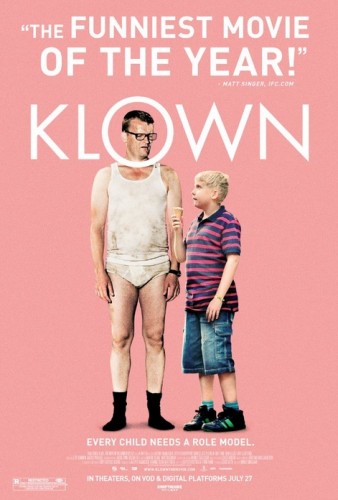

Klown‘s plot revolves around a canoe trip with lascivious intentions and Frank’s aspirations toward fatherhood. When we first meet Frank, he shows overt disdain toward child rearing until a doctor friend inadvertently lets slip the news that Mia (Mia Lyhne), Frank’s girlfriend, has a bun in the oven. There’s no better way to change a man’s tune than to directly challenge his folly, and when Mia expresses concern over Frank’s potential as a dad he does what any desperate dimwit would do: he “kidnaps” Bo (Marcuz Jess Petersen), Mia’s sullen, portly twelve-year-old nephew, and coerces the boy into canoeing with him and Casper on the pretense of bonding.

Klown‘s plot revolves around a canoe trip with lascivious intentions and Frank’s aspirations toward fatherhood. When we first meet Frank, he shows overt disdain toward child rearing until a doctor friend inadvertently lets slip the news that Mia (Mia Lyhne), Frank’s girlfriend, has a bun in the oven. There’s no better way to change a man’s tune than to directly challenge his folly, and when Mia expresses concern over Frank’s potential as a dad he does what any desperate dimwit would do: he “kidnaps” Bo (Marcuz Jess Petersen), Mia’s sullen, portly twelve-year-old nephew, and coerces the boy into canoeing with him and Casper on the pretense of bonding.

Of course, there’s very little a preteen can contribute to a trip saddled with a filthy moniker and born out of a need to get laid. Casper’s the Lothario figure bent on racking up one-night stands with numerous women, while Frank is less content with the idea of cheating on his significant other. In fact, boiled away of its particulars, Klown codes Frank as the noble hero; he wants to prove himself to his partner, rather than two-time her. But it’s those particulars that make Klown such a breathtaking farce of bad decisions and worse outcomes. No action taken or choice made here ends up for the better, at least not in the end. In a way, the film is tragic. Try as they might, Frank can’t help but screw up and Casper just can’t keep it in his pants. They’re the Laurel and Hardy of perversity, winding up in mess after mess thanks to their joint bumbling.

And the shocking absurdities on display in Klown are very much a team effort by both men. Klown is the capstone effort of the decade and change Hvam and Christensen have spent working together and portraying alternate versions of themselves (think The Trip but exponentially bawdier). Their act lives and dies on the chemistry they share, and so their utterly natural rapport– whether they’re just talking or canoeing for their lives while being chased by an angry mob– represents the cornerstone element of the entire film. If Klown can be said to have any degree of humanity, it’s housed deep within the screen relationship they’ve crafted with one another.

That’s not quite so heartwarming as it sounds, mind. At first blush there’s almost nothing human whatsoever about the way each man strives endlessly to outdo and one-up the other in rank stupidity and atrocity. Maybe from a distance their crimes seem small, but taken in total Frank and Casper compile a laundry list of misdoings ranging from armed robbery to sexual misconduct to endangering minors. Up close they must seem like monsters, and yet there’s something that’s innately human to their behavior. Frank and Casper almost seem to be competing to see who’s the most debauched and negligent, though admittedly their brand of relentless foolishness feels specific to their gender.

As bad as things get– and the film reaches peaks of vulgar grandeur so explicit that I can’t even hint at them here– Klown does maintain a continuity of sweetness, even if the minds behind the picture aren’t occupied foremost with that quality. As the narrative moves forward, Frank and Bo do eventually find common ground together, developing kinship amid orgies, drug abuse, and penile antics. It’s perhaps just logical to assume that their mutuality is just part of the game that Christensen, Hvam, and Nørgaard are playing here; in the Hollywood version (the film has already been snatched up for remaking by none other than Todd Phillips), that might well be the ultimate point. Here, it’s just a gag, and as soon as Frank and Bo begin understanding one another their relationship ends up taking five steps back with cringe-inducing efficacy.

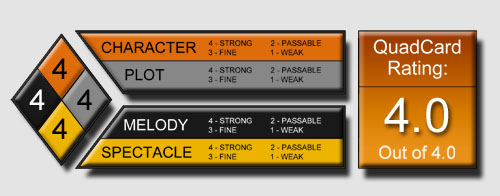

G-S-T RULING:

That pervasive sense of discomfort defines Klown from start to finish, but there’s subtext to the movie’s wanton immorality. Perhaps that’s only a mild reassurance for the faint of heart. Hvam and Christensen know their craft all too well, and they can unsettle and fluster with obscene precision. There’s something, though, to the way that their capers are so often met with the disapproving, disbelieving gaze of the film’s female characters. St. Jerome, Tertullian, and every scholar promoting the idea that the responsibility for man’s downfall belongs to woman have it all backward if Klown has anything to say on the matter. Frank and Casper don’t need any assistance in that regard; they’re entirely capable of realizing their undoing by virtue of their own gifts for ludicrous mayhem. When they do find themselves in need of guidance, the other men of the film all too happily step in to offer terrible advice. And yet when Klown ends on a note that echoes The Hangover— though with more punishing purpose– there’s a sense that Frank and Casper will endure, along with their pigheaded friends, even under withering glances from their spouses. Their stubborn determination to perpetually be in the wrong almost feels noble. Godspeed, you inglorious Danes. Godspeed.

4 Comments

Colin "Fitz" Biggs

I can’t see Danny McBride pulling off a remake. Not as good as this anyway.

Andrew Crump

Nor me. The weird thing is that Klown almost feels like a direct descendant of The Hangover (and even has an echo of Grandma’s Boy), but it outdoes both of them in every way possible. I don’t think an American version of this film will rise above what Christensen and Hvam have done here; at best, it can only match the American films that precede it.

Tyler

Nice write-up, but I think you have to look pretty deep to find any kind of sweetness in this film. I can’t believe that it is based on a TV show, and it makes me wonder what Danish TV is like. I first heard about this movie from a coworker at DISH who said it was the raunchiest thing he had ever seen. That sounded like quite a recommendation, so I added it to my Blockbuster @Home queue. Even with my friend’s warning I was not ready for what I got, and I found myself shocked by what I was seeing (which doesn’t happen often). You are exactly right about how these guys are masters at making you uncomfortable, and that is no easy feat in our desensitized modern world. I am glad that I only rented it though because it is not one of those movies that you will want to watch over and over again.

Andrew Crump

Well, there’s definitely SOME sweetness there– that’s the whole arc Frank has with Bo. But the film isn’t so interested in being sweet as it is in being vile, and it is much better characterized by the latter characteristic than the former. Still, there’s an undercurrent of sweetness in Frank’s story with Bo; it’s just not the point of the whole thing.

I’m not sure how you get away with this sort of stuff on TV, though I suspect that it’s somewhat toned down. (From what I hear, “somewhat” still amounts to “not much”.) Regardless, I’ll watch this again when I have a moment– it’s on Netflix Instant now. Which surprises me, but there you go.