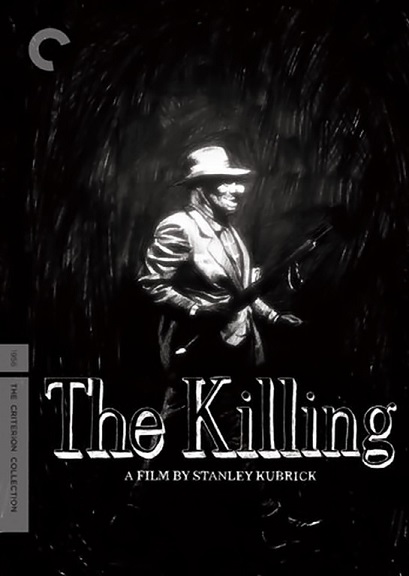

The Killing

Directed by: Stanley Kubrick

Written by: Stanley Kubrick, Jim Thompson

Starring: Sterling Hayden, Colleen Gray, Vince Edwards, Jay C. Flippen, Elisha Cook Jr., Marie Windsor

Cinematography by: Lucien Ballard

Music by: Gerard Fried

Release: May 20, 1956

When you think of Stanley Kubrick, which of his many films come to mind? The Shining? 2001: A Space Odyssey? A Clockwork Orange? Perhaps Dr. Strangelove? If there’s a single common throughline linking each of these pictures together- though many might argue that there are many- it’s influence, as in the influence that his work has had on cinema as a medium from the 60’s going forward. Note, for example, how much impact The Shining had on the horror genre, or the ways in which Dr. Strangelove informed any number of pictures ranging from Mars Attacks! to The Hudsucker Proxy. There’s no denying how much Kubrick’s work shaped the course of film over his decades-long (but still too short) career.

So maybe overtly pointing it out is stating the obvious, but it bears mentioning when discussing The Killing, one of his more frequently overlooked films from the 1950s. If Kubrick is one of the fathers of contemporary film, then The Killing could be one of his most unappreciated children; after all, it serves, more or less, as the entire basis for Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs, a movie that’s often cited as a clone of Ringo Lam’s City on Fire. Whatever elements Tarantino mined from that picture, it’s The Killing that happens to be the true forebear of the auteur’s directorial debut- and by his own admission, no less. Without The Killing, you simply have no Reservoir Dogs, and maybe even no Quentin Tarantino, though that might have been a good thing depending on who you ask.

So maybe overtly pointing it out is stating the obvious, but it bears mentioning when discussing The Killing, one of his more frequently overlooked films from the 1950s. If Kubrick is one of the fathers of contemporary film, then The Killing could be one of his most unappreciated children; after all, it serves, more or less, as the entire basis for Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs, a movie that’s often cited as a clone of Ringo Lam’s City on Fire. Whatever elements Tarantino mined from that picture, it’s The Killing that happens to be the true forebear of the auteur’s directorial debut- and by his own admission, no less. Without The Killing, you simply have no Reservoir Dogs, and maybe even no Quentin Tarantino, though that might have been a good thing depending on who you ask.

It’s strange, then, that Kubrick’s small, intimate crime masterpiece tends to get lost in the shuffle when discussing his filmography. Of course, the various parts that make up the “why” are obvious; the scale that The Killing operates on is minute compared to that of Kubrick’s more celebrated films. Rather than span months, years, and beyond, the events of The Killing unfold over just a handful of days as its central heist plot steadily comes together, building momentum even as one of the players involved puts the entire plan at risk through his own spinelessness. The relative slightness of the film belies the ambition seen in much of the auteur’s later work.

More noteworthy is the film’s straightforward demeanor and no-frills presentation. There’s nary a star child to be found here, nor any haunting, impossible photographs- just mean, lean, bare-bones genre muscle from start to finish.When Sterling Hayden consigns himself to his fate in the closing shot, giving himself up to armed detectives after a botched escape attempt, his actions leave no room for ambiguity; we know where our hero and his compatriots stand with no question as to how they arrived at their respective fates. Kubrick designed The Killing as a closed circuit instead of leaving it open-ended.

Maybe that’s just a symptom of the film’s position in Kubrick’s body of work. The Killing occurs very, very early in his oeuvre, and at the time of its release was the single longest feature presentation he’d made. Amazing to think that after making a series of pictures clocking in at around or just over an hour’s length, he went on to craft colossal, towering epics a’la Spartacus and Barry Lyndon which clock in at around 180 minutes apiece. Perhaps Kubrick saw films like The Killing as springboards for the rest of his career, projects that allowed him to develop the resources necessary to tell the stories he really wanted to tell; in other words, they’re necessary stepping stones that led him to the most acclaimed stretches of his filmmaking life.

But though it displays a much-reduced scope compared to his grander pictures, The Killing nonetheless lays the groundwork for every acclaimed, iconic film that followed it; minor though it may be, it’s perhaps the best gateway Kubrick film. The current of dark irony that runs throughout the narrative, the tight, highly controlled sense of pacing, the very intentional mis-en-scene…everything that one needs to understand Kubrick lies within The Killing‘s eighty minute frame. That, perhaps more than anything, is what gives The Killing retrospective weight. Certainly, it’s a very good film taken on its own merits, but when examined in context with the rest of Kubrick’s cinema it is, perhaps, the key to understanding him as a filmmaker.

That’s no small feat given the movie’s elegant simplicity. Hayden’s career criminal lead, Johnny Clay, plots a robbery of a racing track and assembles a septet of various individuals- a betting window teller, a track bartender, a corrupt cop, a sharpshooting killer, and so on- to aid him in his venture; once gathered they conceptualize and eventually execute his plan with mechanical precision. Care to know the twist? They actually succeed. It’s the weakness of the crew’s aforementioned milquetoast that ends up costing each man his life- spared from his involvement, they all would have come out of The Killing significantly wealthier.

The group carries out their scheme with the sort of repetitive orchestration seen in the routine that defines each race we watch over the course of their planning and burgling. In other words, they’re just beasts of burden engaged in their own brand of pursuit, but they’re not after glory or renown- just themselves. Yet their goals aren’t entirely selfish- save for, perhaps, bent policeman Randy Kennan, who needs the money to save his own skin, and hired gun Nikki Arane, who only seems to accept his role for the chance to shoot something. The bartender needs the money to care for his ailing wife; the cowardly betting window teller needs it to prove to his duplicitous and unfaithful spouse, Sherry, that he can give her the life she wants; Johnny needs it to run away with his lover, Fay, and marry her. Noble enough aims, even if the means to their ends is anything but.

And maybe that’s where Kubrick finds his grey area- in the morality of violent crime. Johnny sculpts his plan so as to be nearly victimless; no one aside from Nikki and a handful of bar patrons winds up getting hurt as the heist occurs, and the only significant bloodshed comes afterwards when Sherry’s lover, Val, ambushes Johnny’s crew. As Kubrick’s camera surveys the carnage, there’s a distinct sense of judgment- everyone has gotten what’s coming to them, except that for the most part the burglary is predicated on good intentions. No one, save for the aforementioned exceptions, gets involved just to line their own pockets; there’s reasonable motivation to be found here, and The Killing walks a fine ethical line as a result. Are these men truly criminal? Obviously, yes, because they’re committing a crime, but Kubrick invites us to empathize with them nonetheless- especially poor Johnny, who almost gets away but winds up being foiled by his own lack of foresight and inadequate packing skills. Turns out he really wasn’t so bright after all.

What’s Kubrick saying in all of this? That we ought to show some sympathy for the bad guys? By today’s standards, the criminal-as-hero trope is one that’s well-tread, but in post-war America Johnny Clay was a newish figure, a sort of rebellion against Hollywood’s idealized vision of heroism. More than anything, though, it’s the way that Kubrick maintains a rigid sense of authority over the film that makes The Killing essential viewing.