Joon-ho Bong’s Snowpiercer is a grimy and dismal vision of the future. There’s nothing cheery about a post-apocalyptic future, and if living has more in common with being a prisoner of war (cramped conditions, no windows, questionably non-descript food) it might not be worth struggling for survival. But it’s not all doom and gloom. True, this is about preserving the last souls on Earth, but it’s not without a handful of wacky Korean conventions that few aside from Joon-ho Bong can provide with such style and balance. Even as the last hope for humanity speeds its way through our now frozen planet, there’s still time for humor peppering a multitude of societal issues that play out and remind us why we should not go quietly into that frigid good night.

Joon-ho Bong’s Snowpiercer is a grimy and dismal vision of the future. There’s nothing cheery about a post-apocalyptic future, and if living has more in common with being a prisoner of war (cramped conditions, no windows, questionably non-descript food) it might not be worth struggling for survival. But it’s not all doom and gloom. True, this is about preserving the last souls on Earth, but it’s not without a handful of wacky Korean conventions that few aside from Joon-ho Bong can provide with such style and balance. Even as the last hope for humanity speeds its way through our now frozen planet, there’s still time for humor peppering a multitude of societal issues that play out and remind us why we should not go quietly into that frigid good night.

The film, the equivalent to say Mad Max on a train, is presented with healthy doses of charm, vitality, action and irreverence which heighten  the captivating elements in this narrative. But among them, the most oddly disconcerting element to the story finds that even as the passengers are the last hope for the human race there still exists a class system – one that is split right down the middle between the haves and the have nots. It doesn’t seem too far-fetched. Even in this dismal future, Darwin has to fit in there somewhere right?

the captivating elements in this narrative. But among them, the most oddly disconcerting element to the story finds that even as the passengers are the last hope for the human race there still exists a class system – one that is split right down the middle between the haves and the have nots. It doesn’t seem too far-fetched. Even in this dismal future, Darwin has to fit in there somewhere right?

There is some thick rationale to the events, especially the fact that the hope of the human race (racing on a continuous system of rail lines that connect all the continents) lies with the idea and resources of one man, Mr. Wilford; he and his “sacred engine” are deified because of it. It makes sense because he has given them life by continually speeding them away from death. Now what sets this story off, and what makes it as engaging as it is at times, is sci-fi. It’s a highly unlikely future, so there’s comfort in that, but it is still a future that is based on current ideas, concerns and social issues.

Aside from the plot, Snowpiercer is visually remarkable. From the diesel stained innards of the rear cars to the opulence of the forward cars the set design and locomotive world is an impressive backdrop to this fascinating and highly stylized character study. This mostly English-speaking cast Joon-ho Bong has assembled is quite the ensemble of well-known actors and features surprising turns from master thespians who bring a lot of weight and legitimacy to this haunting vision of the future.

It’s a little scary thinking of the logistics of such a film; even if you suspend disbelief there is a constant wondering of how things possibly drifted so south of the well-intentioned and purposeful last hope for humanity. They must really have thought about possible dissent and means to suppress such actions. Keeping people in fear keeps those in charge in charge and the rest to their own devices. Yet people can only take so much and the lack of simple hygiene and means of sustenance is enough to incite rebellion but there’s something else that drives the survivors to stand up to those in charge. Snowpiercer builds very well revealing layer upon layer of mystery as these people seemingly fear for their lives from the people who are trying to keep them safe.

Even with a Korean director at the helm he finds a way to skip past the translation barrier and is able to chalk it up to the technology of the time in this advanced but apocalyptic future. Evans leads the English speaking cast but Kang-ho Song adds just the right flavor and helps get the rebellious group from car to car. Doing so is an adventure in itself and reveals more of the mystery. There’s not a single thing about this that isn’t fun or inventive even if the source material in the story is somewhat depressing. The film has many dashes of humor, both tension breaking and dark, yet perhaps the most delightful part of Snowpiercer (and most any film she’s in really) is Tilda Swinton who takes great pleasure in chewing the scenery.

For a film with environmental leanings it rarely leans on that part of the story. In fact, the idea of survival is cleverly internalized to make the struggle to survive on the train a slightly easier task than braving the subzero terrain outside. It’s more about humanity than the environment, obviously, but the seeds planted don’t equate to a cautionary tale. On the contrary it’s a Luc Besson film set in a series of claustrophobic and increasingly bizarre rooms. Not a bad thing but it drags and could have benefitted from hauling a few less cars around the track. In fact, Harvey Weinstein thought the same and lopped 20 minutes off but his trimming tends to be too liberal (thankfully you can still find theaters showing the entire film).

Asian narratives tend to be very operatic, with larger than life villains who sometimes just don’t realize that they have become evil. In the case of Snowpiercer there’s a need to have someone fit that bill sitting in the first train car. The film is inventive and engaging but when Evans, Hurt and company are finally able to pull back the curtain and peek at the wizard, as expected, there’s bloated monologues about life, lessons, purpose and vision; all the while the words are laced with delusion that has only been exacerbated by riding the Wilford rails for nearly 20 years. That’s where the film loses steam, in terms of originality but it’s still a wildly fascinating ride.

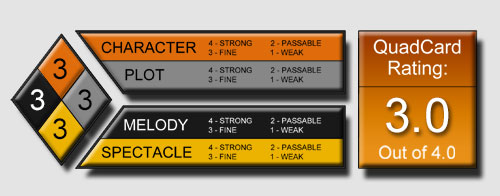

G-S-T RULING:

Snowpiercer is fascinating in design, character and ambition but as it gets a little too convoluted – despite the straight-forward plot and direction – it just slightly misses the mark that would have made this one for the ages. That said, it’s still a satisfying trip and if you’re a fan of Joon-ho Bong, then this won’t disappoint.